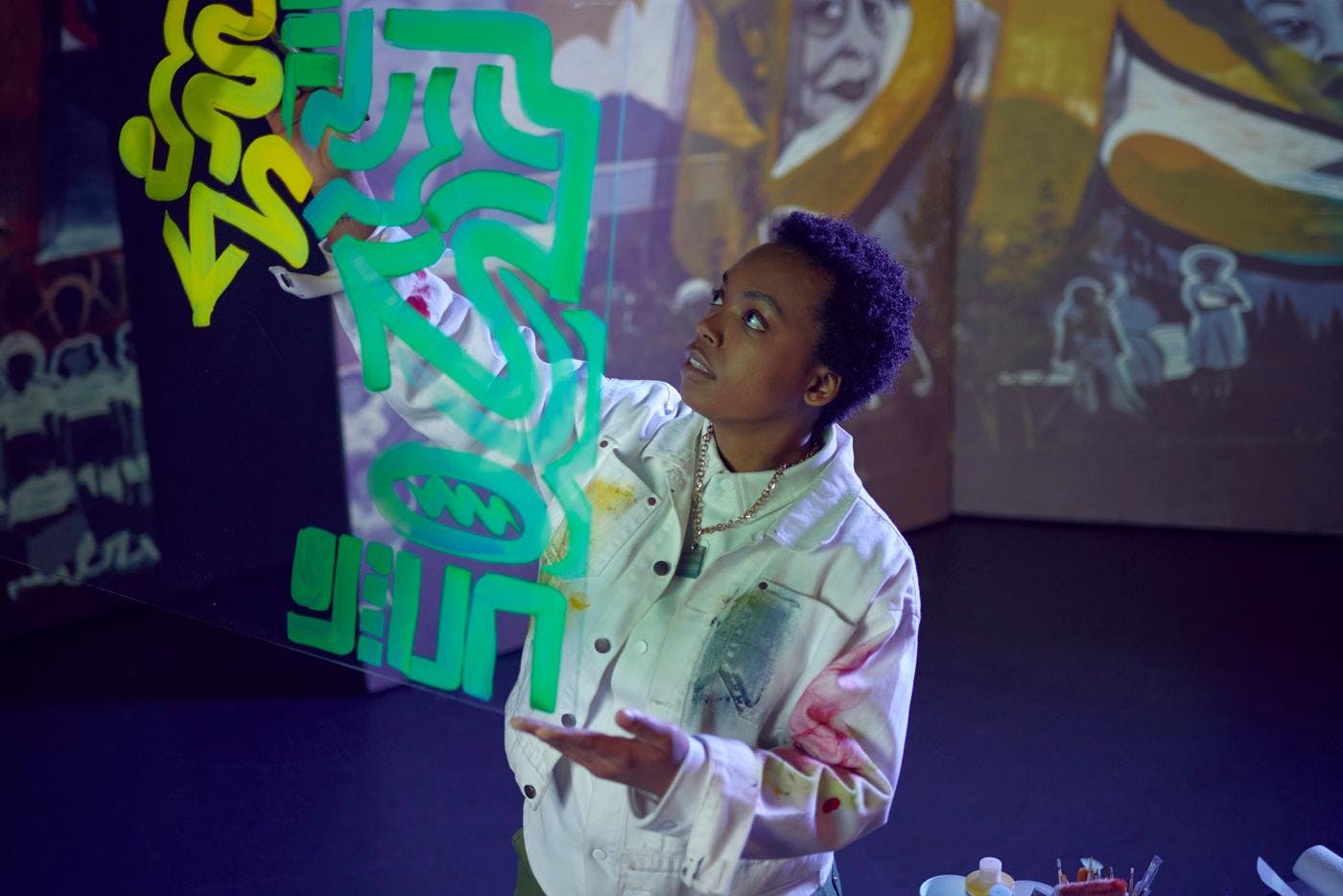

Watch: Debora Moore

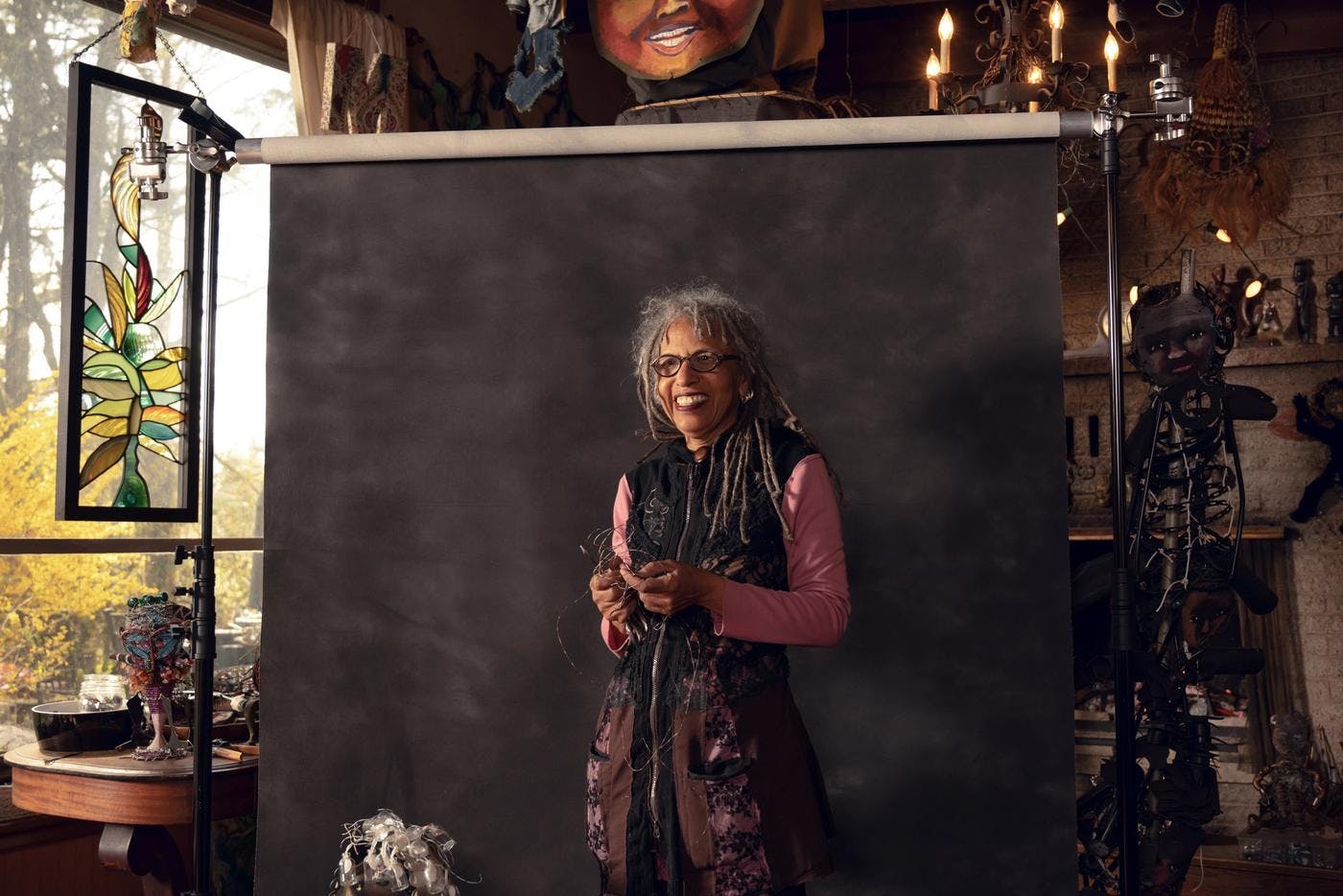

A pioneer of glass techniques, this renowned creator is one of the few Black female artists in her medium.

The first Black art instructor in Washington was an experimental artist ahead of his time.

by Jas Keimig / June 6, 2023

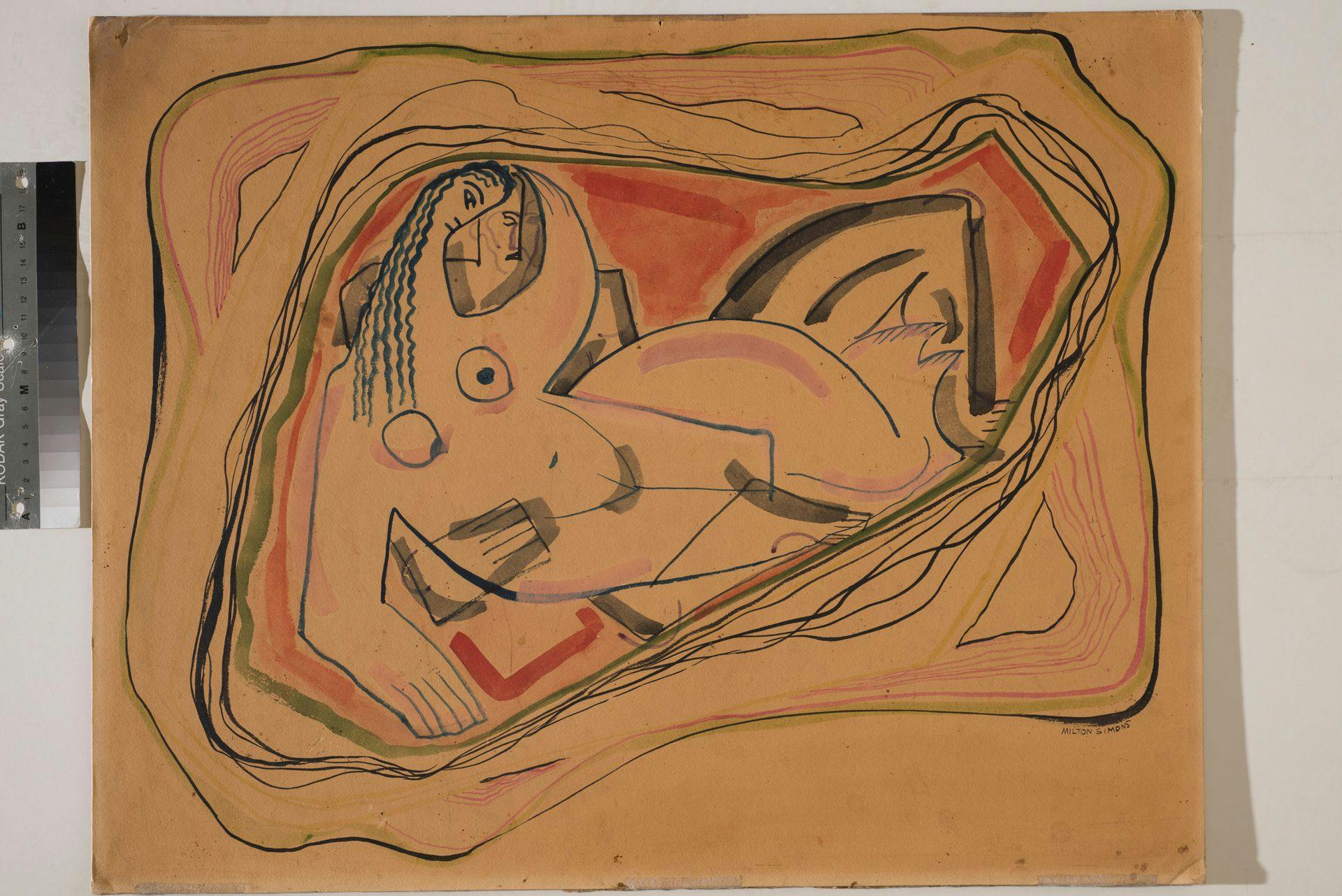

In Milt Simons’ 1957 masterpiece, “Introspection,” the landscape of Seattle seems pulled from the inner recesses of a dream.

The city’s buildings, rendered as dark rectangles that disappear into the horizon, occupy the bottom section of the massive painting. Above a choppy mountain range looms a sky full of murky blues, dirty whites, drippy blacks and translucent red ochres; two moonlike objects mirror each other. Floating above it all is a naked Black figure, back turned toward the viewer, a flute raised to his mouth in some silent song.

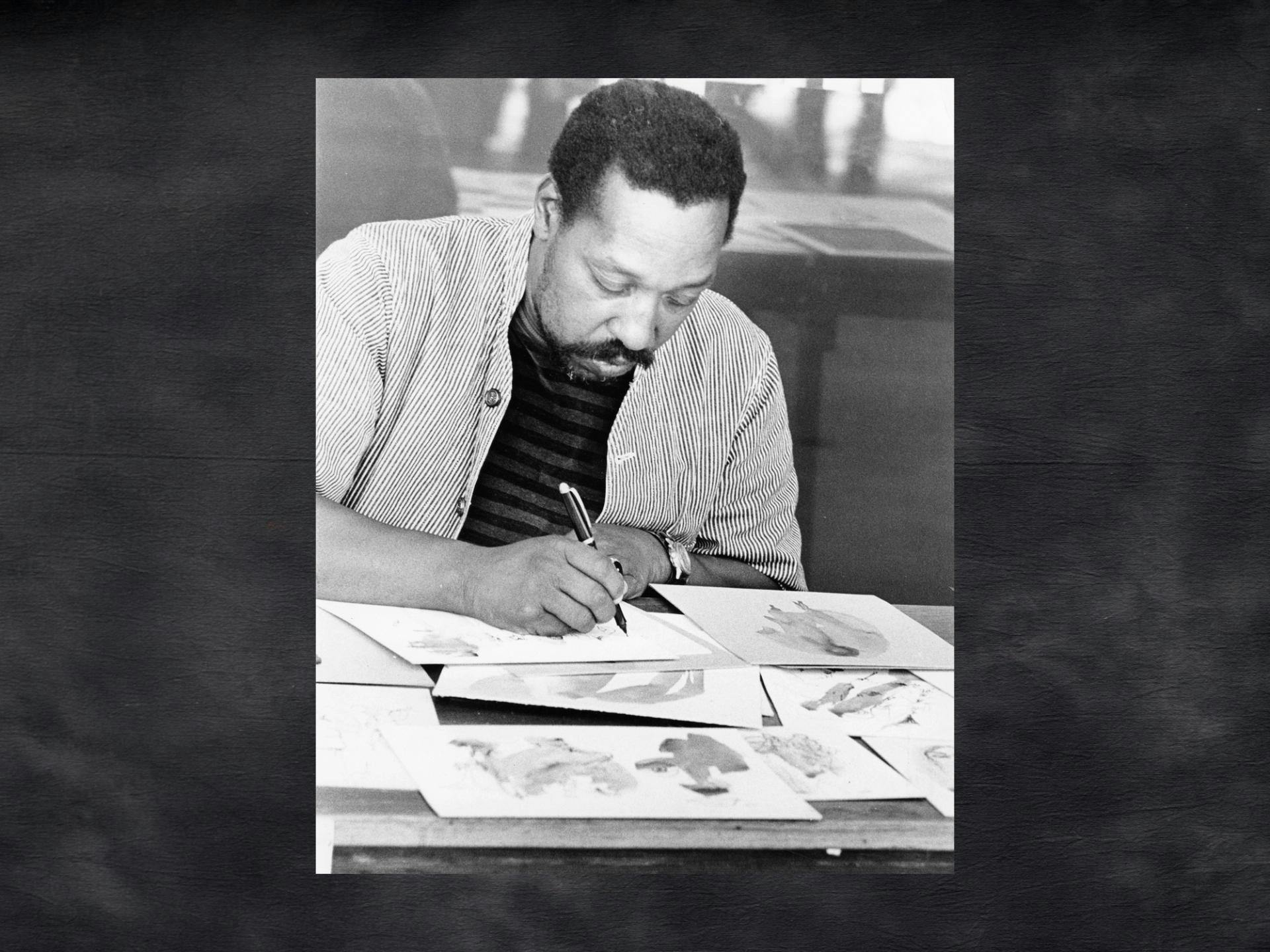

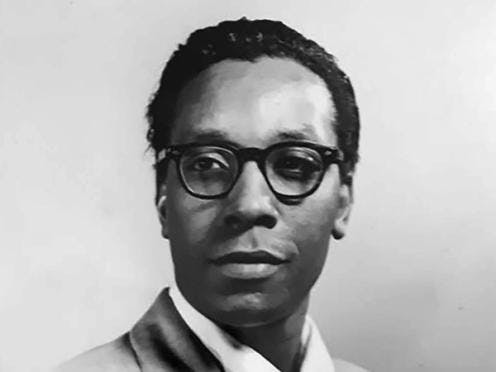

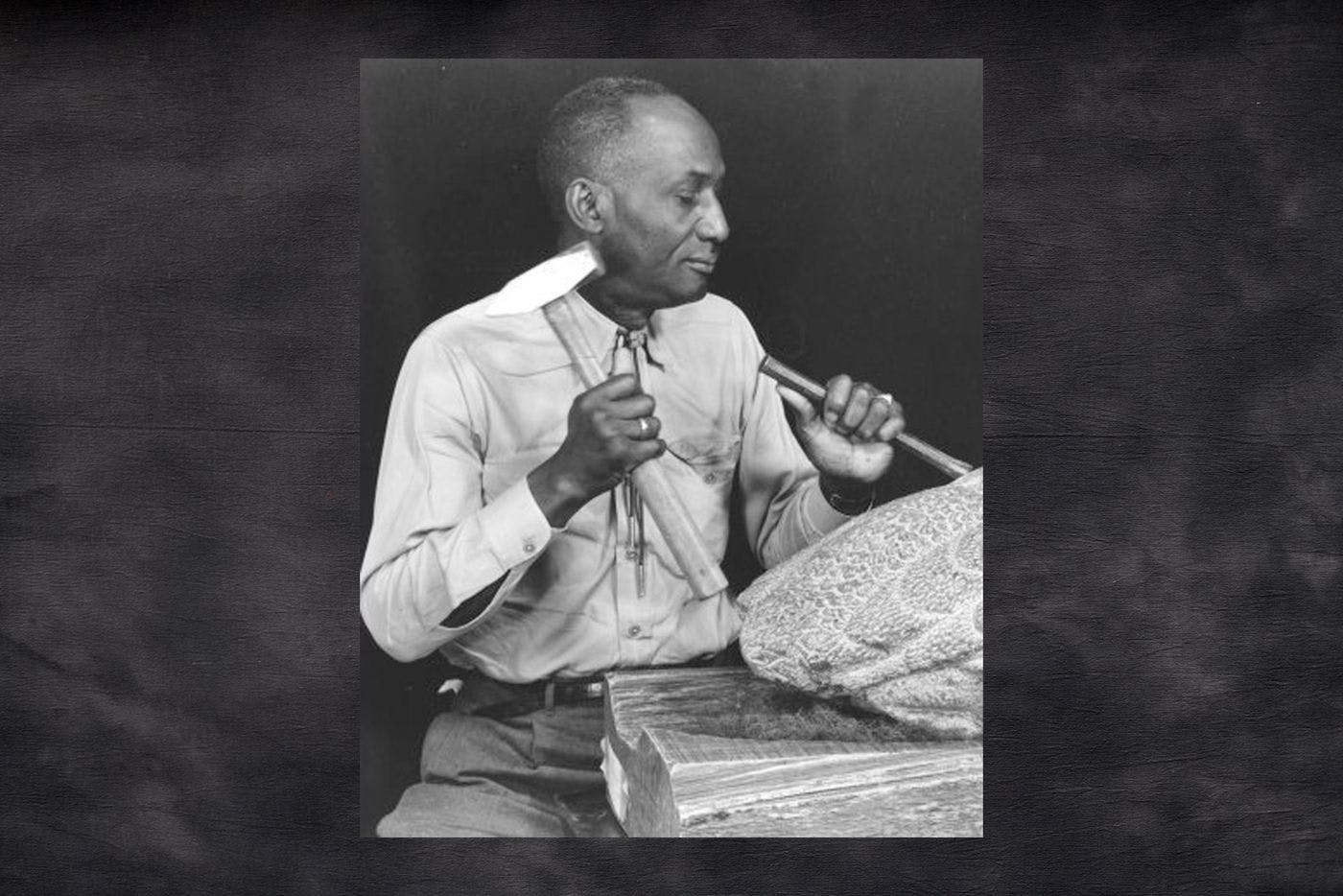

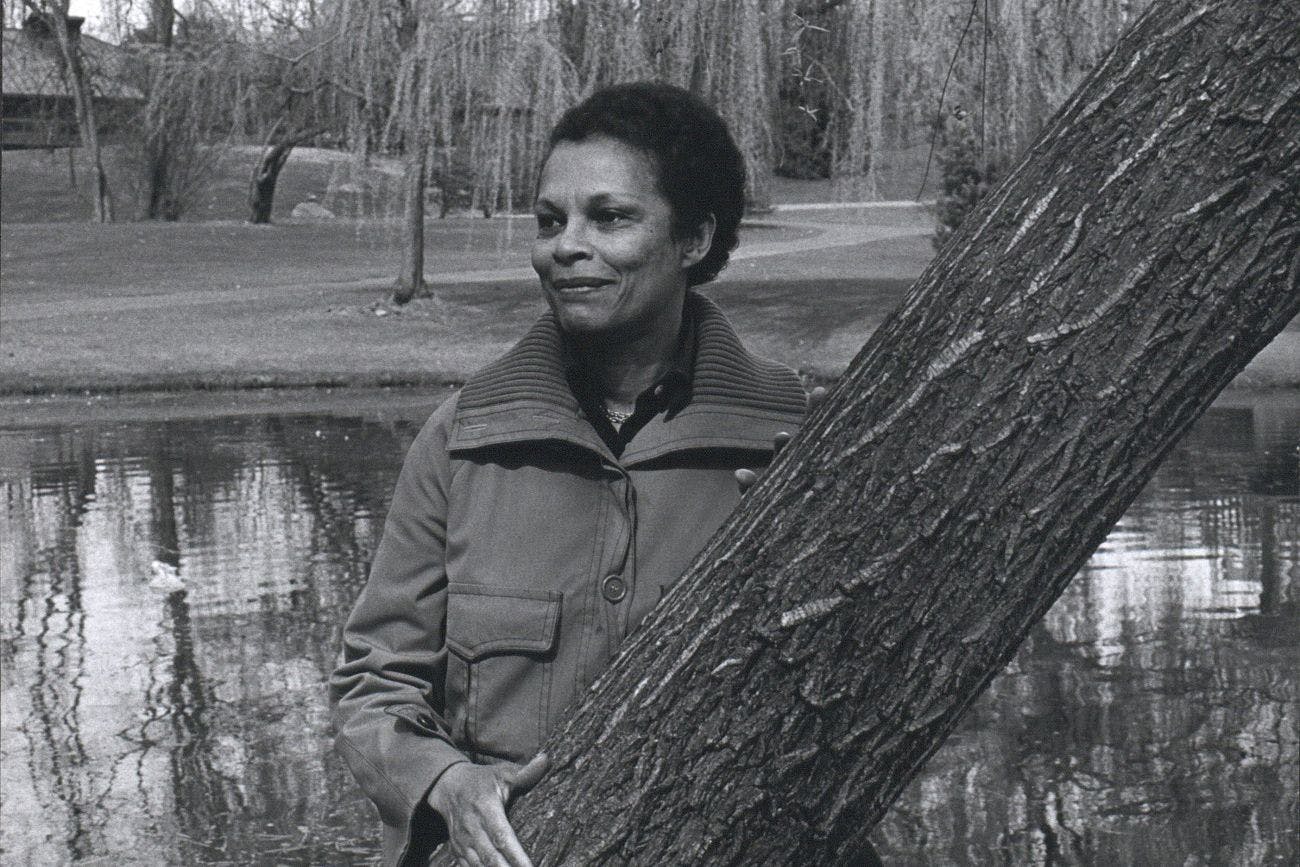

Active in the Seattle art scene from the early 1950s until his passing in 1973 at age 50, Simons was one of a handful of Black artists showing work, playing music and directing his own gallery here during that era. A man of many talents — painter, dancer, poet, musician, teacher, amateur fencer — Simons’ boundary-pushing creations reflected his belief in the synthesis of many art forms.

“There is design in music. Color has wavelengths and speeds, and so has sound. Middle C is yellow, for instance. It goes up into infra-red and ultraviolet,” he said in 1966. “Tensions between colors are like tensions between sounds and shapes. There is a relationship really but, paradoxically, not really.”

With ancestral roots in Yakima and Tennessee, Simons was born in Seattle in 1923 and grew up mainly in the Central Area. He was close to his maternal grandfather, Andrew Marshall, who was of Black and Native ancestry and who encouraged his artistic ambition.

After graduating from Garfield High School in 1940, Simons served in the Army during WWII, then used the G.I. bill to study art at both the Burnley School of Art in Seattle and the Art Students’ League at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York.

Never one to limit his modes of expression, throughout his career Simons also studied dance under Syvilla Fort in New York and Virginia Ryan in Seattle, and studio piano and counterpoint at The Cornish School (now Cornish College of the Arts).

Most active as an abstract and figural painter in the 1940s and ’50s, Simons’ paintings took inspiration from surrealism, Spanish master painter El Greco, and spirituality, visible in his long-bodied figures and unearthly landscapes. His study of music and dance comes through in his paintings too — both in the ways his colors blend and bend into one another and in his frequent depictions of musicians playing instruments.

In his undated work “Song of Life,” Simons paints a giant cellist in shades of blue and beige, mid-song and looming over Seattle. The player’s head is thrown back in concentration; the cello itself looks like it’s made of human organs, due to the way Simons has mashed colors and shapes together. It’s an arresting blend of art-historical references with a modern sensibility.

His artistic experimentation continued in the early 1960s with what he called “spatial paintings,” wire constructions draped with painted canvas covered in blobs of yellows, reds, pinks and blacks.

“Some ask me if I don’t think it’s cheating to use an actual third dimension in paintings,” Simons said of this work at the time. “I can’t see why. It seems to me much more honest than simulating one with paint. I stretch the canvas and rip it and tear it and model it to change its organic structure so that it becomes part of the medium. But it’s always paint and canvas that I use.”

Despite Simons’ talents and vision, his paintings did not receive the attention they deserved during his lifetime.

"Although my work was praised, particularly in illustration, fashion design, figure painting and other commercial lines, I was flatly refused any position, again because of color,” Simons wrote in 1971. “Many times I have broken up brushes, thrown away my paints and work in deep remorse and bewilderment. But I am an artist. To function is to create.”

That creative drive guided the way he lived, which was often against the grain of expectation. Simons was the first Black student at Burnley (which later became the Art Institute of Seattle), and, when promoted to teacher there in 1951, became the first Black art instructor in Washington. That year he married Marianne Hanson, a white painter and musician of Swedish descent, at a time when mixed-race marriages weren’t common.

"He never was granted very much recognition,” Hanson told The Seattle Times in 1999. “The Northwest scene was controlled by a few artists and there weren’t many galleries at the time.” But Simons didn’t wait for gallerists to make space for his identity and ideas; he and Marianne founded the Milann Gallery in Madrona in 1959.

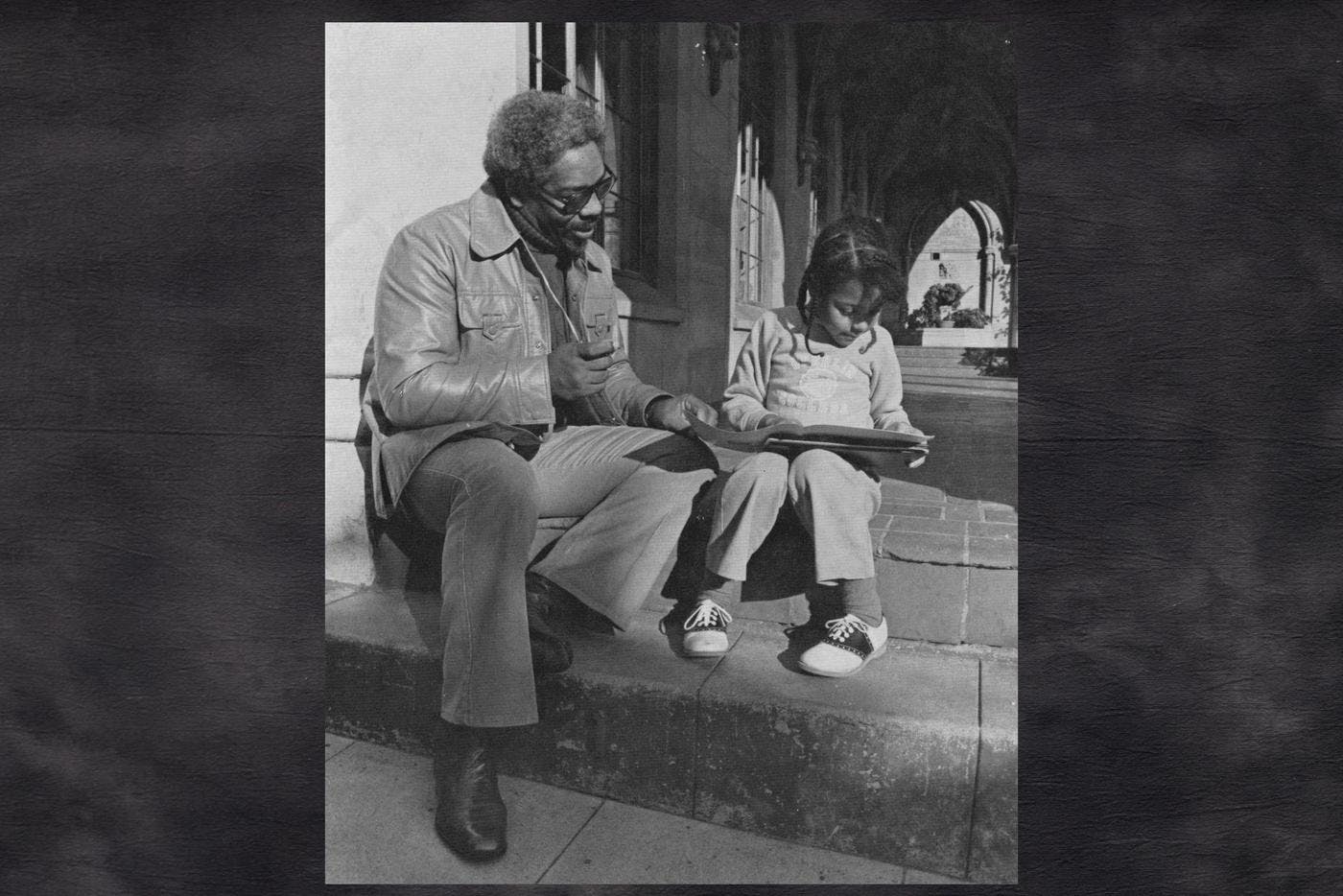

There, Simons and Hanson displayed their own work and work by artists outside the gallery system, as well as art made by their young son, Serge, born in 1953.

They also taught art in the space and often hosted performances by Simons’ band, the Puget Sounds, featuring Simons on vibraphone and Hanson on piano. The gallery closed in 1961, and in 1968 the space became the Seattle Black Panther headquarters. After Milann’s closure, the family went on a brief sojourn to San Francisco in 1962 where they opened Fulton on Baker, a gallery focused again on displaying art ignored by the mainstream.

Back in Seattle, as it became apparent that his paintings weren’t gaining traction, Simons focused on his multimedia and music work. In the mid-’60s, he found a kindred spirit in Paul Dusenbury, another multimodal Black artist who believed in the synthesis of art forms. After meeting in 1966, the two worked with Everett’s Creative Arts Association on a visual-art show called “Habitat” that sounds, by all accounts, freaky and experimental.

With Dusenbury on the slide projector and Simons working the tape recorders, visitors’ visual and auditory senses were “bombarded with color, light, and sound” as projected images and music engulfed the space, wrote The Everett Herald’s Jeanne Metzger. The bombastic exhibition kicked off a boundary-pushing artistic relationship that would last until Simons’ passing in 1973.

In 1968, Simons and Dusenbury co-founded the Central Area School of the Performing Arts, an arts organization dedicated to developing improvisational learning in children of all backgrounds. And in 1971 the two formed Jasis, which stood for Jazz-Art Spontaneous Improvisational Synthesis.

With Simons on the vibraphone, Dusenbury on piano and flute, Milt Gerard on bass and Jimmie Williams on percussion, the band had a far-out sound and perspective. Jasis occasionally performed on KING-FM’s Jazz at Home show as well as at cafes around town. Their improvisational album Jasis: Spontaneous Improvisation combined Indian classical music and American jazz. (Listen to side 1 here.)

The first track, their take on the Indian classical raga “Bhimpalasi,” blends the dreamy, futuristic tones of the vibraphone with the jazzy inclination of the flute, both anchored by fast-paced, irregular drumbeats. Today, a master tape of the rare, out-of-print record is kept at the University of Washington Ethnomusicology Department, and department archivist John Vallier calls it a “jewel of the collection.”

“This captures a certain era in making music,” Vallier says. “It sounds like free jazz, but at the same time it does have structure, a lot of modes being played in different scales. I think the music creates a lot of thoughtful space.”

So how did this brilliant, talented artist fall into obscurity? While his premature death certainly contributed, so did the racism prevalent in the national and local art scenes at the time.

One formative story: As a teenager, Simons was awarded a national art scholarship sponsored by Disney, only to have the offer rescinded after the awarding committee learned he was Black. That betrayal made him wary of showing his work nationally, opting primarily for local spaces such as WHY Gallery, Seattle Art Museum and Henry Gallery. But even here, Simons’ work was never formally represented by any prominent galleries.

“It’s difficult because with some of the bigger museums, if they’ve never heard of them, they don’t want to even know … They think if the artist was any good or worth looking at, they would already be famous,” says David Martin, curator at the Cascadia Art Museum in Edmonds and a historian who has advocated for Simons’ work since the late ’90s. “My whole thing is the opposite. There’s some artists who were better than the artists who were famous.”

While Simons’ art never fit neatly into prescribed boxes of “Pacific Northwest” or “Black” art, his fantastical paintings literally imposed Black figures into the Seattle cityscape, indelibly underlining the Black community’s contributions to the city. After Simons’ death in 1973, Hanson fiercely promoted her late husband’s oeuvre, restoring his paintings and drumming up gallery and museum interest in his works until her passing in 2015.

But there’s still so much to uncover. The couple’s son, Serge, a retired car mechanic now in his late 60s who married Dusenbury’s daughter Rebekah, did not follow his parents into the arts, but reports that he has preserved a trove of Simons’ unsold paintings and unheard music demos. Among those treasures includes a Simons creation called the “sito”: a stringed musical instrument that is a cross between an Indian sitar and Japanese koto.

In a 1948 self-portrait, Simons portrayed himself against an emerald-green background, wrapped to his neck in a black coat. His name, “Milt,” is painted in orange script on the bottom right corner. Using thick brushstrokes, the blues and reds he used to paint his brown skin peek through as kinetic dashes of green frame his face. His gaze is lowered, lost in thought — perhaps reflecting on his future as an artist.

Even though much of Simons’ work was overlooked in his time, talent exists whether it’s recognized or not. And recognition can come at any time, even when long overdue.

Editor’s note: The Cascadia Art Museum in Edmonds, WA, is currently working to restore two of Milt Simons’ paintings: “Untitled (still life with roses by a window),” oil on canvas (1958), and “Milt & Wife Marianne Hanson,” oil on canvas (1955). Fans of his work — and of Seattle’s Black art history — can support this conservation effort via the museum’s Adopt-a-Painting program, which gives art enthusiasts the chance to support restoration through direct donation.

Black Arts Legacies Writer

ARTIST OVERVIEW

Painter, musician, educator

(1923-1973)

A pioneer of glass techniques, this renowned creator is one of the few Black female artists in her medium.

An influential member of the noted Northwest School, the Central District sculptor turned his home into a community center for artists.

As a direct connection to the Harlem Renaissance, this often overlooked painter inspired generations of Seattle movers and shakers.

Salvaging old cloth and scrap metal, the longtime Seattle sculptor finds beauty in what’s discarded.

This Seattle artist channels his personal history and activism into vibrant murals and abstract paintings.

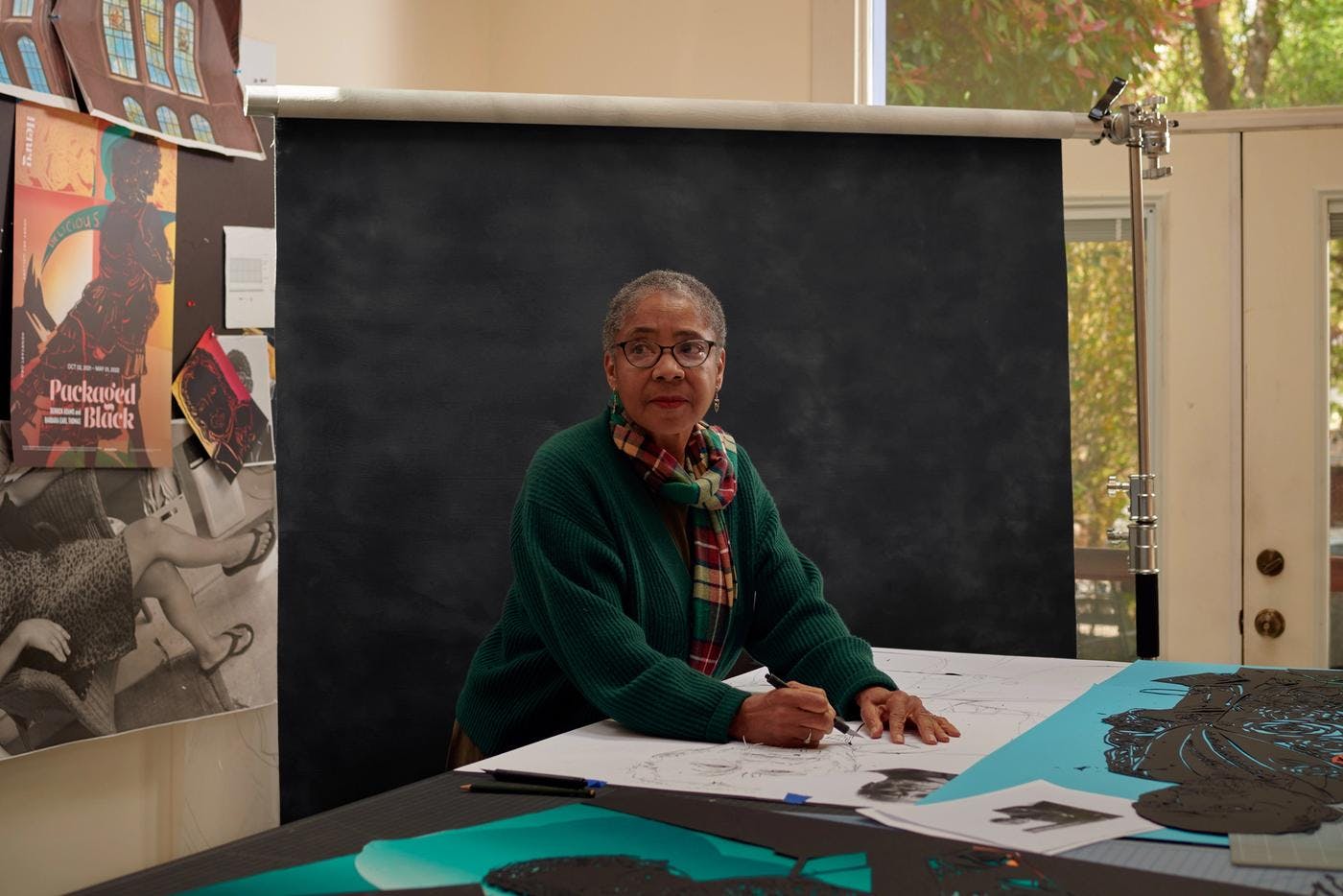

With meticulous skill and a communal approach, the longtime Seattle artist has cut her own path.

Two curators separated by decades turn homes into galleries to support artists.

The influential art teacher uses books, found objects and photography to provoke thought and shift perception.

The late couple's house is now a cultural center that inspires the next generation.

The late director, producer, stuntman and teacher used film and video production to lift up the voices of Seattle’s Black community.

Through public murals, collaborative projects and custom sneakers, this artist is leaving her footprint on Seattle history.

The curator, gallerist and artist is resisting the art establishment with bold immersive experiments.

From intricate portraits to multistory murals, the artists bring Black history and bold color to the cityscape.

Through ceramics, sculpture, jewelry and public art, the multifaceted artist makes Black history tactile.

A fount of knowledge for the jazz community, the trombonist and living legend is shaping the next generation of Seattle musicians.

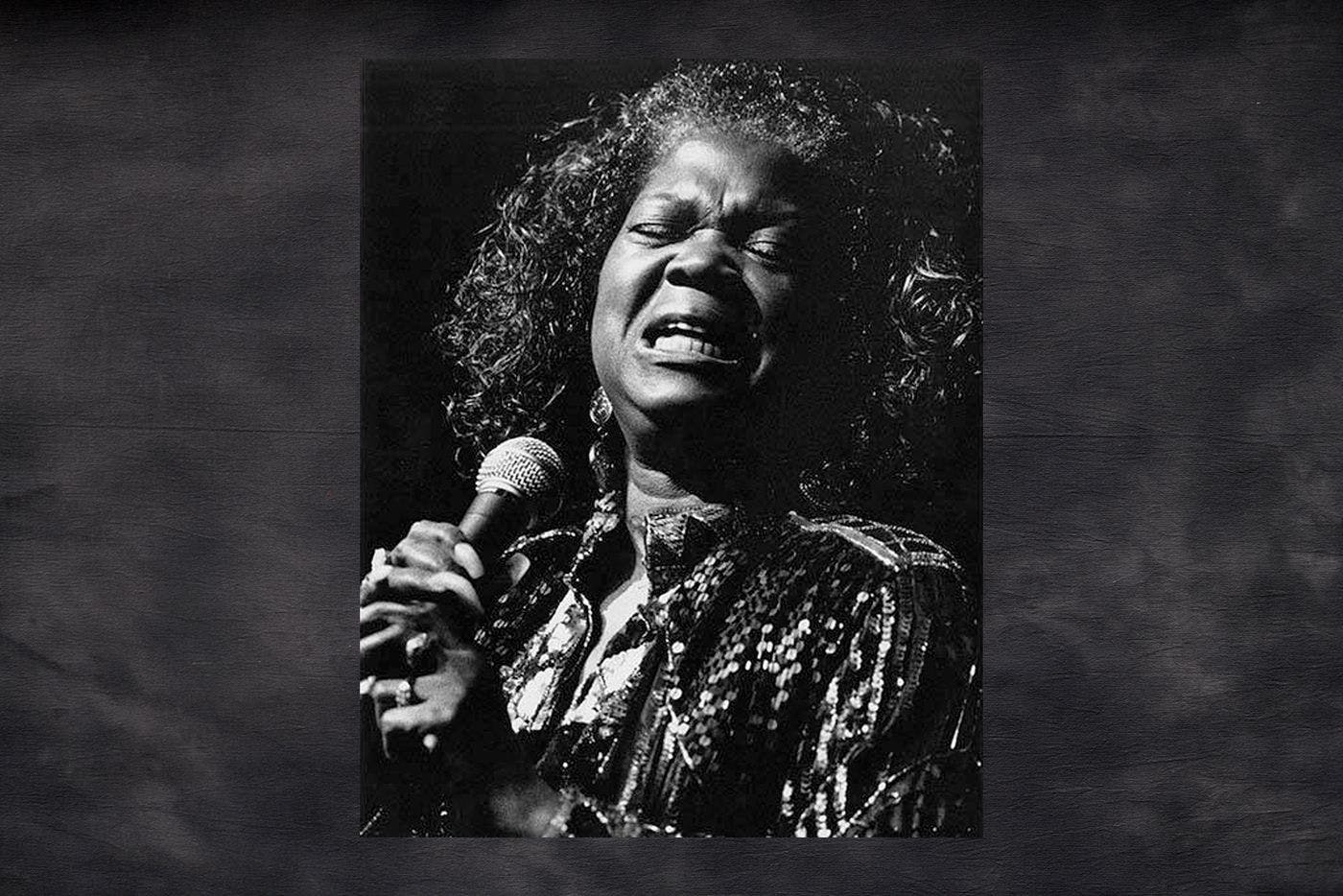

With a voice like ‘honey at dusk,’ the singer helped put Seattle’s early jazz and blues scene on the map.

For three decades, this Seattle DJ electrified the airwaves, paving the way for future Black radio personalities.

A poet at heart, this soul singer/songwriter is inspiring the next generation of Seattle musicians.

As a founder of Digable Planets and Shabazz Palaces, the Seattle rapper has pushed hip-hop to the outer limits.

The Seattle rapper keeps his memories of the Central District alive with vivid lyrics and a jazz sensibility.

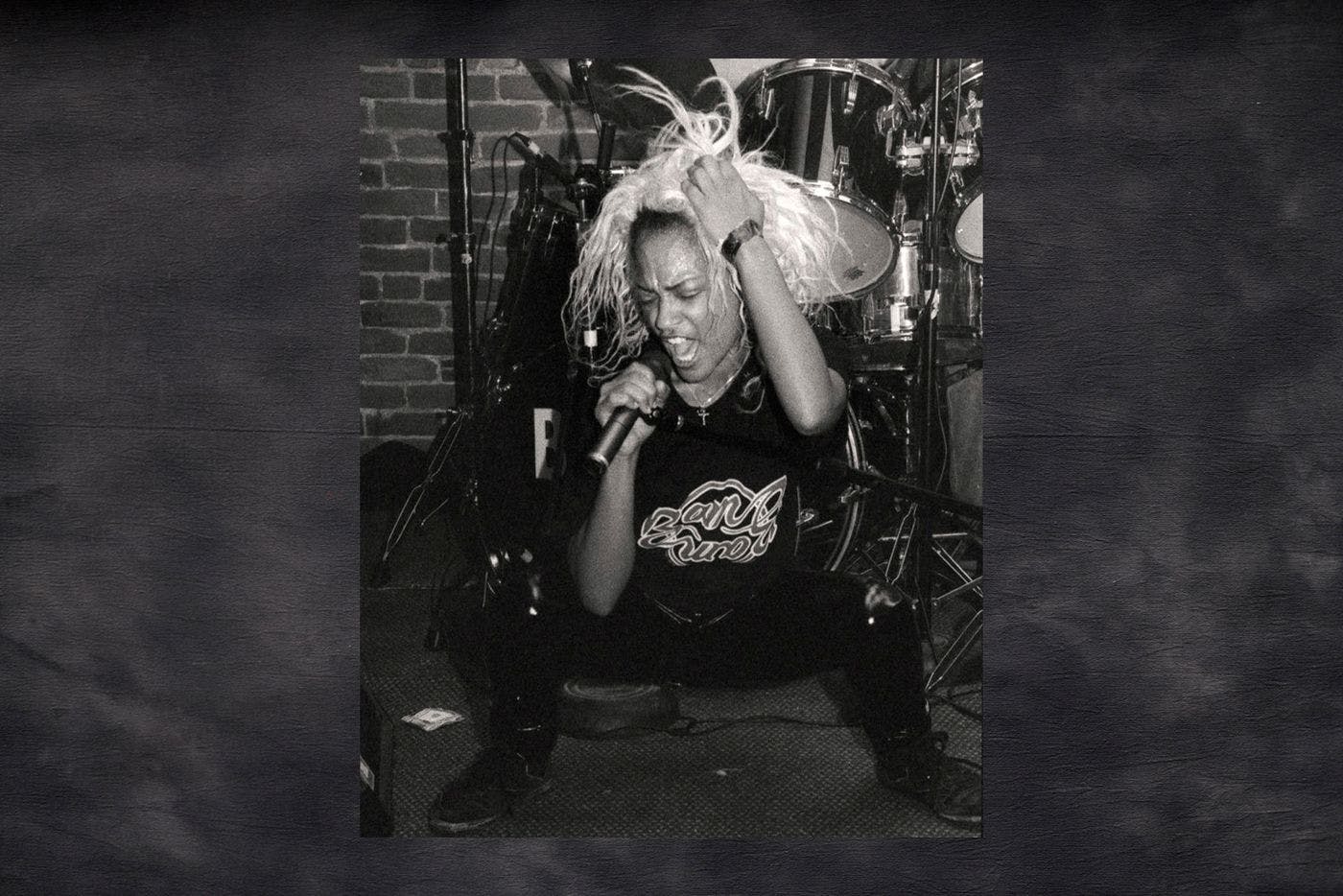

A pivotal figure in Seattle’s proto-grunge scene, the Bam Bam singer has been long-overlooked. Now, rock history is being rewritten.

The talented multi-instrumentalist uses music to string communities together.

Meet a Seattle music pioneer and the band carrying the legacy of Northwest rock forward.

This beloved Seattle DJ found his divine calling in music — and in sharing it with others.

Composing meditative music with a looping pedal, this Seattle cellist has charted her own sonic path.

Thanks to our Sponsors

Your support helps Crosscut create projects like Black Arts Legacies. Learn how you can help with a one-time donation or recurring membership.

Support Crosscut