Tee Dennard

After landing on the stage unexpectedly, this Seattle actor/director’s 50-year career played a major role in the city’s Black theater scene.

The late director, producer, stuntman and teacher used film and video production to lift up the voices of Seattle’s Black community.

by Jas Keimig / May 9, 2023

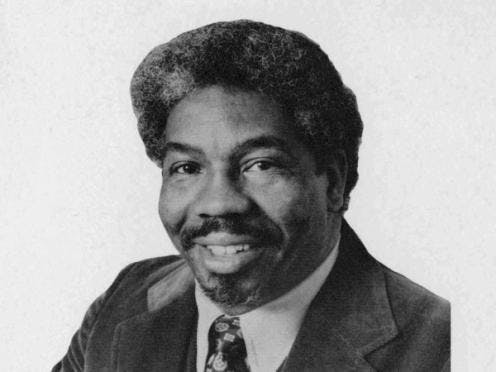

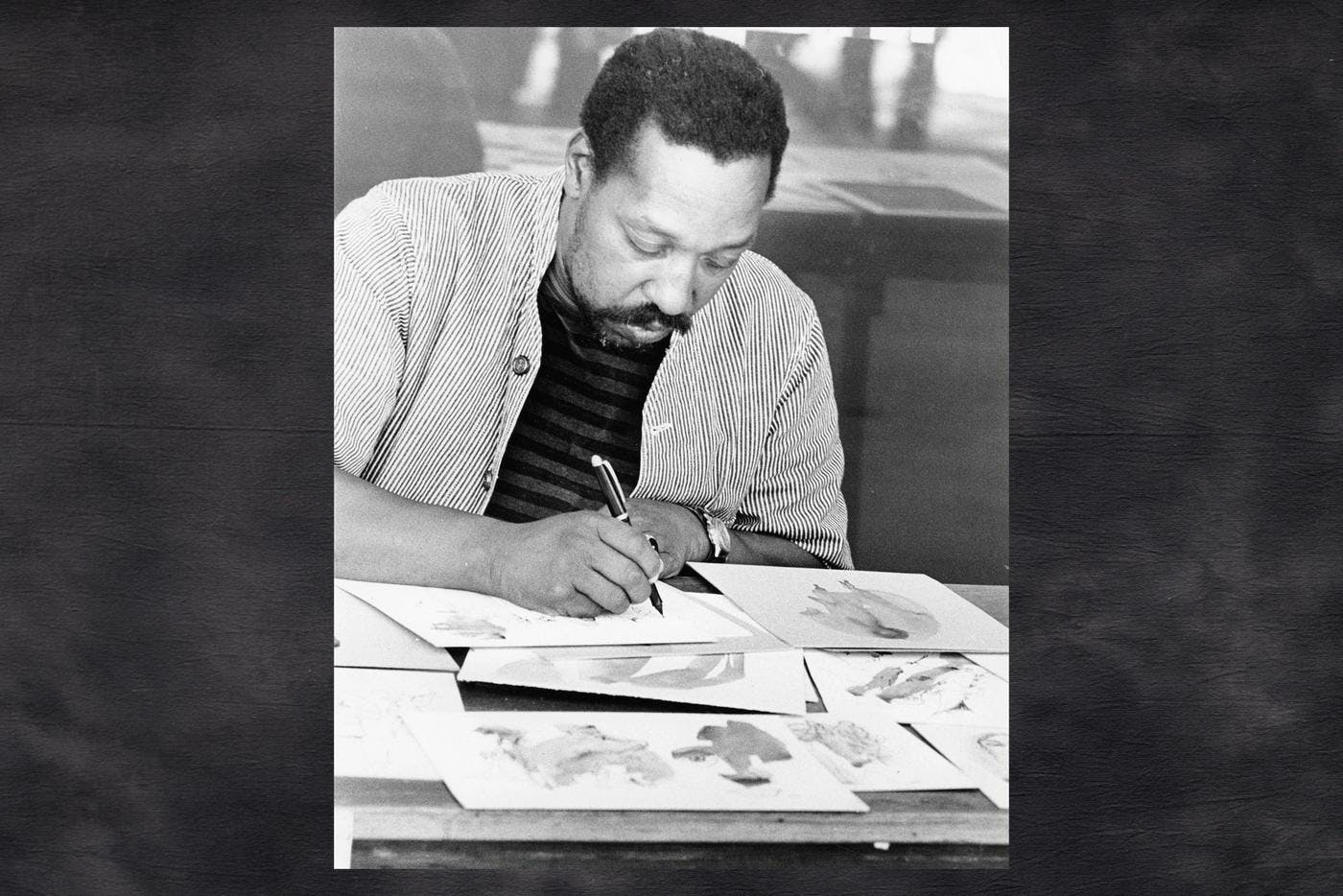

In a Hollywood conference room in 2003, Black folks from around the country gathered to honor Nate Long, the director, producer, stuntman, community advocate, teacher, karate and judo black belt, and giant of Seattle’s Central District who had touched each of their lives.

“I want to set the record straight: Nike says they coined the phrase ‘Just do it’ — that is a lie,” joked Tony Hopkins, Long’s former judo student who later helped him shape the video production curriculum at Seattle Central Community College. “Nate Long would say, ‘I don’t wanna hear somebody talk about wanting to do something — let’s just do it.’”

Throughout his nearly 40 years in media — from his military retirement in the mid-1960s until his death in 2002 at age 72 — Long did just about everything he set his mind to. But his greatest passion was teaching Seattle’s Black youth to harness the representative power of film and television.

“I am convinced that, over a period of time, if we as Black Americans do not see or learn anything about ourselves, we begin to take on the attitudes, concerns and the cultures of the dominant society,” Long wrote in 1981.

In the 1960s, riots rocked Black communities like Watts and Detroit. Prominent Black leaders like Martin Luther King, Jr. and Seattle activist Edwin Pratt were brutally assassinated. Long — then in his 30s — watched TV news coverage of these events, observing the unique power of media to shape perception of the Black community. He also noted how few Black journalists were on screen or behind the camera to guide and contextualize the narrative.

Soon after, Long decided to teach Seattle’s Black youth how to break into that lily-white field. The fact that he didn’t know anything about video production didn’t matter — he simply taught himself how to film and edit, determined to pass those skills on to the young people he knew would shape the future.

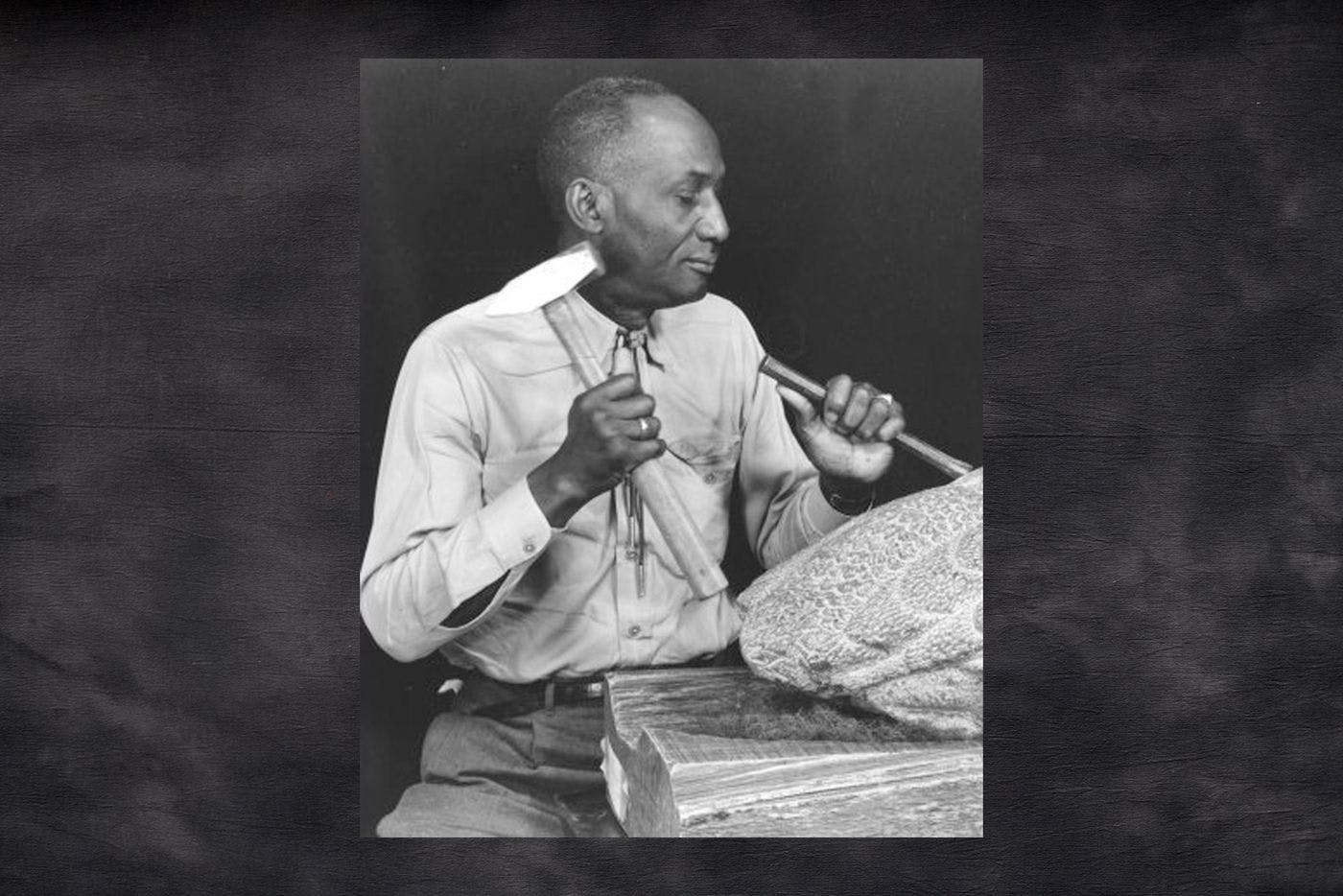

Born in Philadelphia in 1930, Long bounced among foster homes before escaping into the U.S. Air Force in 1948. In 1951, while stationed in Japan, he found judo, “the most influential thing in my life,” Long told the Seattle Post-Intelligencer in 1971. Years of intensive judo training formed the basis of his life philosophy: the attitude, he said, “which says I’m as good as you, and with some training I can excel in whatever field I try.”

Just out of the Air Force and inspired by The Jungle, a 1967 film made by Philadelphia teens about that city’s Oxford Street gang, Long’s first foray into film production was 1968’s Black Summer, created by Seattle-area youth and made possible by a donation of 10,000 feet of film from KING-TV’s news director Jeff Schiffman.

In 1969, buoyed by minimal funding from organizations including Seattle Model Cities, Long converted his Judkins Park martial arts dojo into a classroom and launched Oscar Productions, Inc., a media company dedicated to teaching Black young people technical video production skills.

The company’s first major show was Action: Inner City, a weekly KOMO-TV news program that ran from 1970–1980, hosted by Black youth and covering everything from mental health to Black Christmas traditions to the future of education in the Central Area (as the Central District was then called).

“I want to show pro-Blackness, the good things that are happening in the community,” Long said in 1971. “If a guy hates our show because we are trying to develop some kind of unity in our community, he’s going to have to hate us, because we’re sure trying to do that.”

Airing on a major network didn’t mean the series’ students and producers couldn’t have fun in front of the majority-white audience. As part of Action: Inner City’s programming, Long and Oscar Productions also created the cheekily titled AGGIN News, a weekend afternoon program that aired monthly on KOMO.

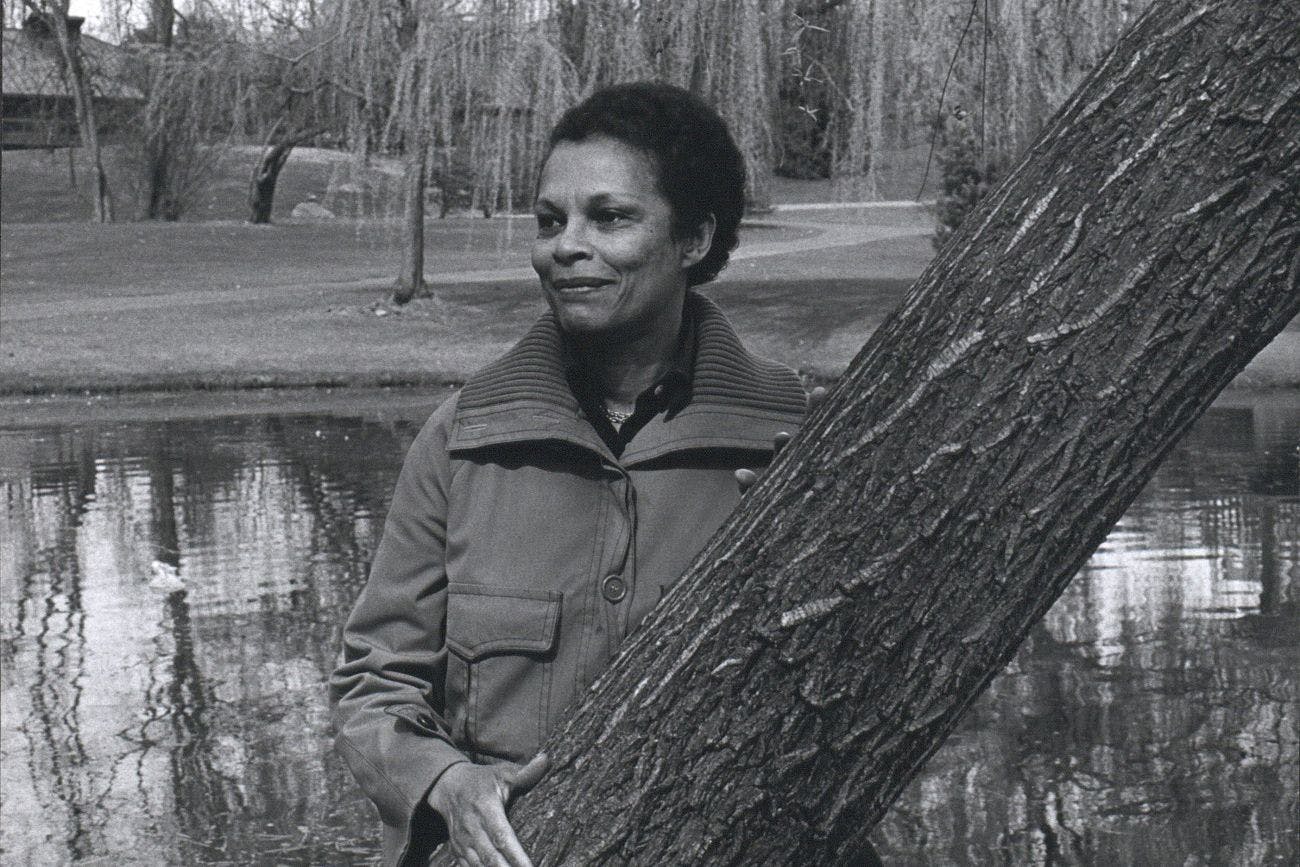

“AGGIN. What does that spell backwards?” Vivian Phillips joked in a 2018 interview. The now-influential Seattle arts advocate worked on the show in 1972, in her late teens. “We were on the ABC affiliate with the AGGIN News and nobody was none the wiser.”

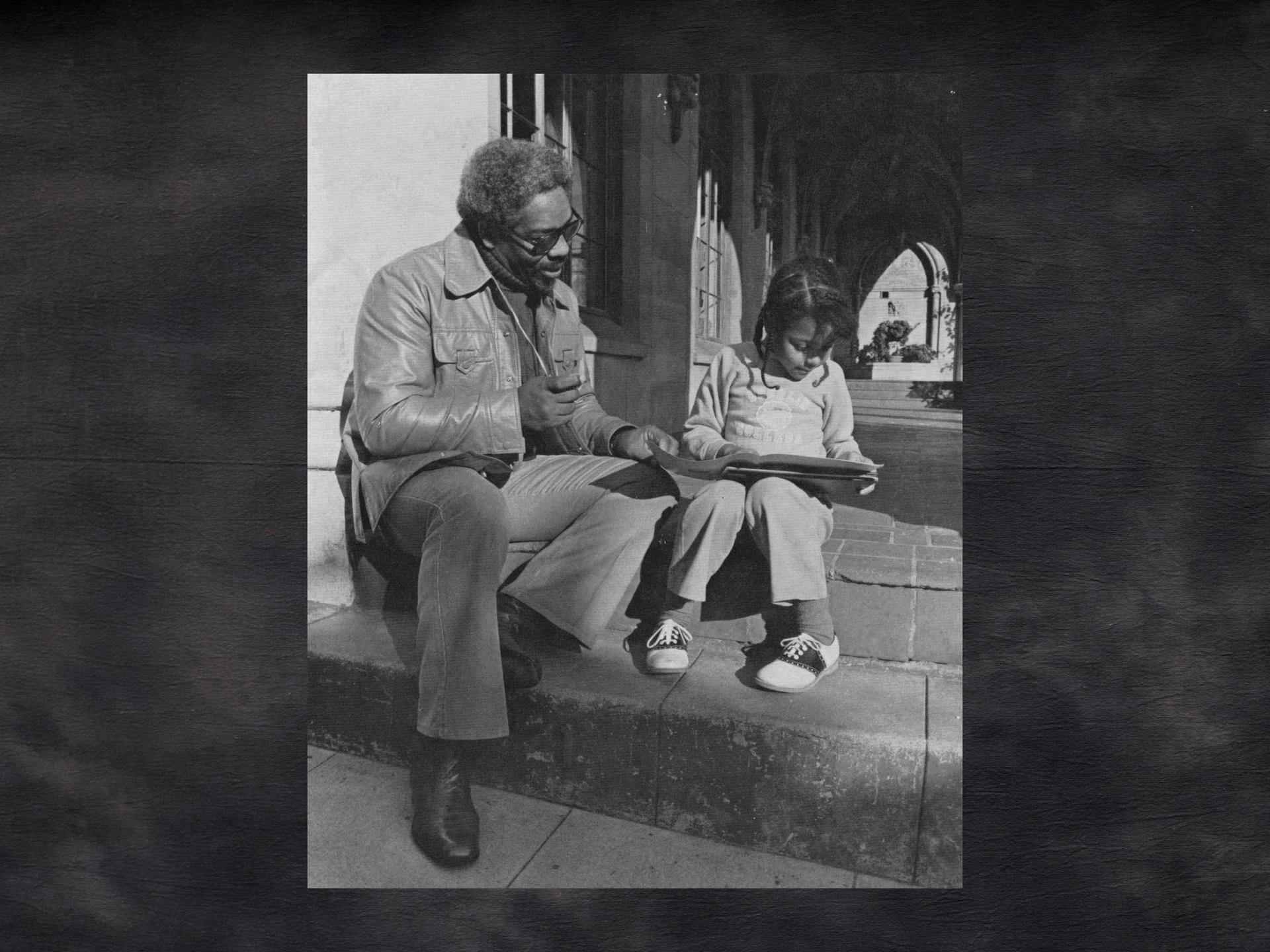

Long’s reputation for producing excellent content about the Black experience grew. In the mid-’70s, Washington State University and KWSU tapped him to produce a groundbreaking five-part docudrama called South by Northwest — starring John Amos, Esther Rolle, Bernie Casey and Rosalind Cash, among many other famous Black actors of the day — which told the stories of Black pioneers in the Pacific Northwest.

Intending it for a middle school audience, Long hoped the program would help foster “a better understanding of the racial mix that comprises this nation,” he wrote in 1981, particularly “Blacks as contributors to this country’s growth and development.”

In 1976, South by Northwest debuted on PBS and more than 80 commercial stations across the country, and went on to win a Corporation for Public Broadcasting Award and a New York Film Festival Award.

To further his industry expertise, Long also worked in Hollywood as an actor, assistant director, gofer, and stuntman throughout the ’70s and ’80s. As always, his previous experience (or lack thereof) didn’t matter. “I wanted to get to know as much about production as possible so I was willing to do anything with any production they’d hire me for,” he told The Seattle Times in 1974.

“Nate Long was a genius and a man before his time. He got into Hollywood to produce and be part of the scene. Even though he didn’t see himself reflected there, he knew he could do those things,” says Beatrice Butler, a former Seattle Central Community College student of Long’s and later a friend.

Using his judo philosophy, Long simply applied himself and did the damn thing, whether that was choreographing Jim Brown’s fight scenes in The Slams (1973), performing stunts in White Line Fever (1975) or playing the fuzz in the Seattle-set crime film Scorchy (1976). Long so impressed Hollywood crews that he wound up assistant-directing several films, becoming the first Black second-unit director on a Disney film with 1982’s Tex.

Long seems to have made an impression everywhere he went. South by Northwest star and former NFL player Bernie Casey — one of the many Black media stars who claim him as an influence — described him as “an old-fashioned, no-nonsense, your-word-is-your-bond, steadfast guy” during Long’s 2003 memorial service. Activist Eddie Rye Jr., singer Joan Houston, and broadcast journalist Lee Carter all got their start as anchors on AGGIN News. Longtime KOMO weatherman Steve Pool and former Fannie Mae CEO Franklin Raines were both part of Action: Inner City early in their careers.

“If I named three people or four people who were instrumental in shaping who I was, [Long] would be one of them,” says former Seattle Mayor Norm Rice, who met Long in 1969 when Rice was 26, working for KOMO and writing his University of Washington master’s thesis on minority access to electronic media for the Urban League.

One of Long’s most lasting marks on Seattle was the two-year video production program he helped found and design at Seattle Central Community College in 1985, intending to make the tools of media representation more accessible to people of all backgrounds. He later established similar programs at Texas Southern University and Texas A&M University.

“He just wanted to add to the creativity and the luster of the way stories were told,” says Cleven Ticeson, a multiple Emmy Award winner with KCTS 9 who studied at Oscar Productions in his youth. “[Nate] knew that it was more than about a college degree. It was about the ability to impart the level of creativity that heretofore was not imparted up here in Seattle.”

Long never slowed his roll in advocating for his PNW community. Throughout the ’80s and ’90s, as vice president of Seattle Community Cablevision, he fought to get cable access for the Central District. In 1992, he founded Seattle’s African American Film Festival. Above all, Long proved that bettering one’s community was just a matter of doing whatever needed doing.

“He had a universal outlook but really believed in the potential of those that look like him,” Ticeson says. “Especially those who were willing to step up to the plate.”

Black Arts Legacies Writer

ARTIST OVERVIEW

Director, producer

(1930-2002)

After landing on the stage unexpectedly, this Seattle actor/director’s 50-year career played a major role in the city’s Black theater scene.

With art, puppetry and real talk, this television pioneer prioritizes children of color.

A pioneer of glass techniques, this renowned creator is one of the few Black female artists in her medium.

An influential member of the noted Northwest School, the Central District sculptor turned his home into a community center for artists.

As a direct connection to the Harlem Renaissance, this often overlooked painter inspired generations of Seattle movers and shakers.

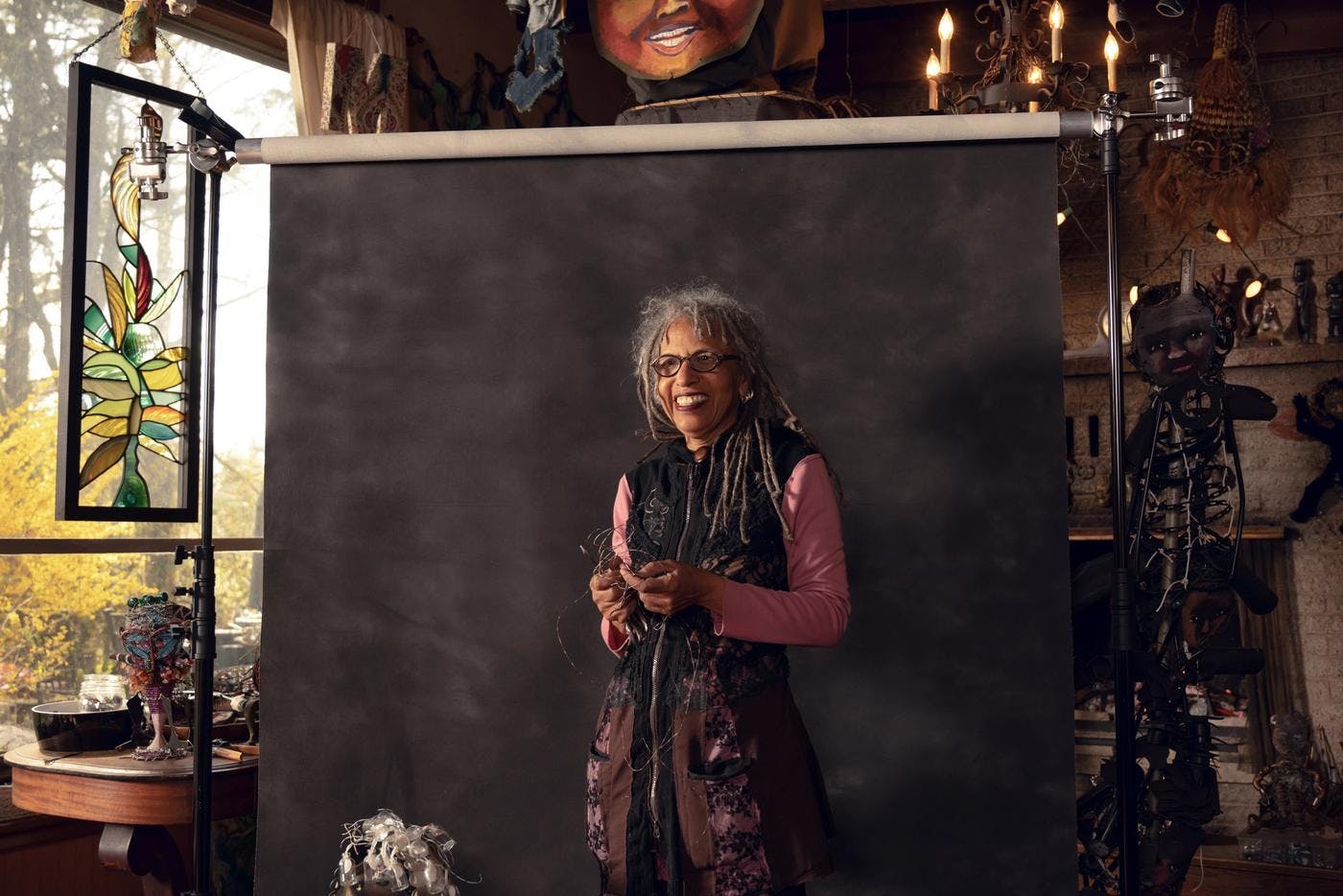

Salvaging old cloth and scrap metal, the longtime Seattle sculptor finds beauty in what’s discarded.

This Seattle artist channels his personal history and activism into vibrant murals and abstract paintings.

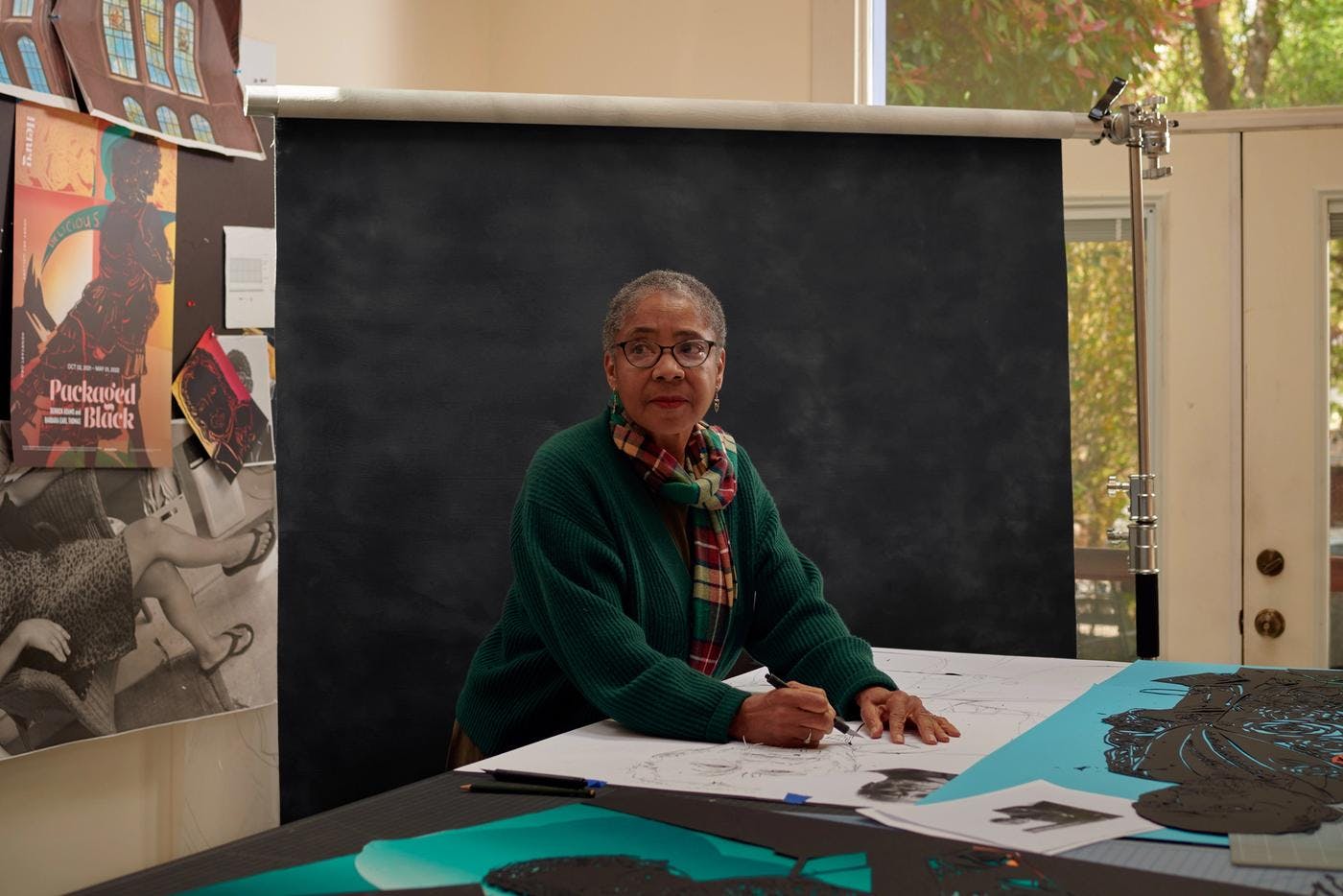

With meticulous skill and a communal approach, the longtime Seattle artist has cut her own path.

The first Black art instructor in Washington was an experimental artist ahead of his time.

Two curators separated by decades turn homes into galleries to support artists.

The influential art teacher uses books, found objects and photography to provoke thought and shift perception.

The late couple's house is now a cultural center that inspires the next generation.

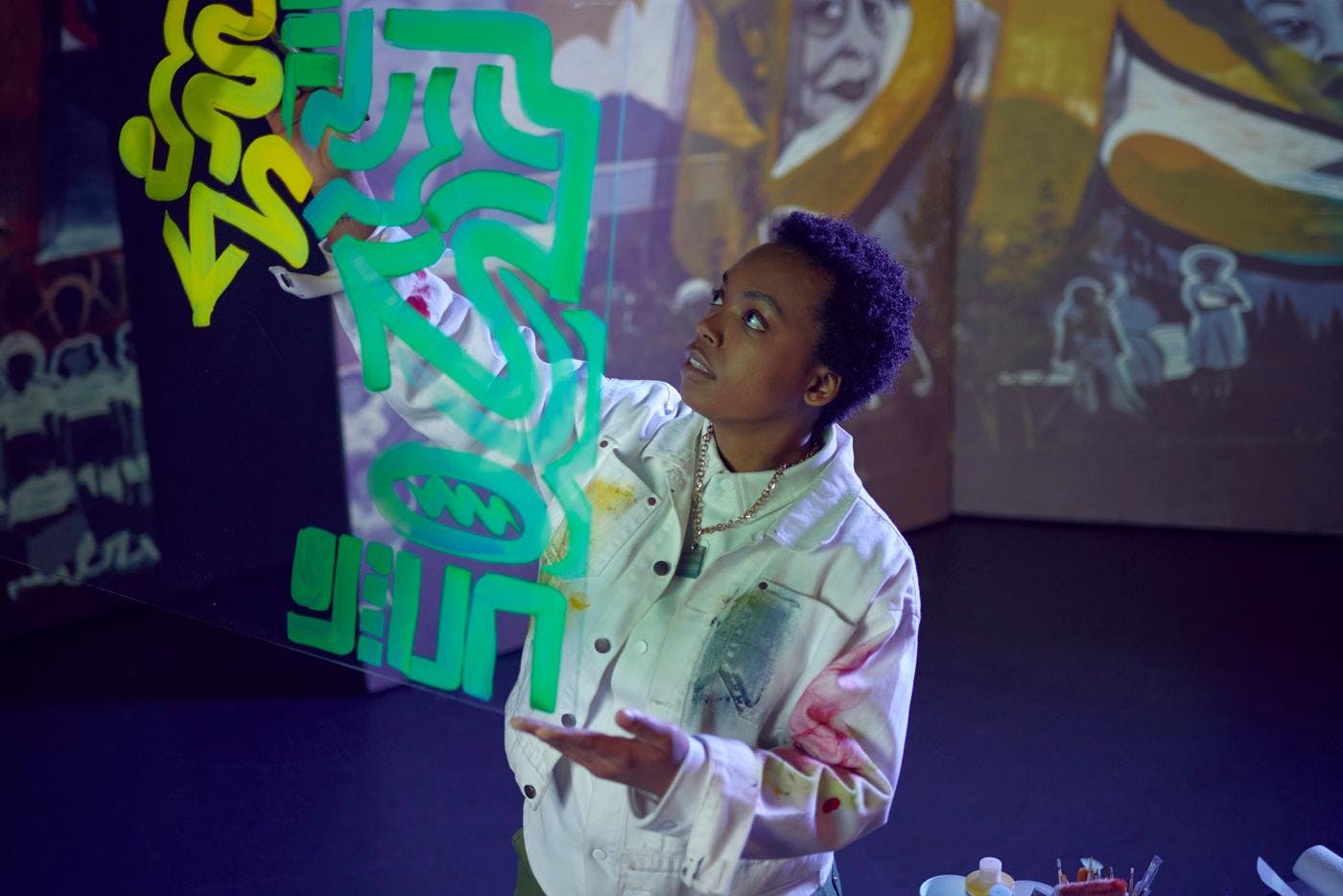

Through public murals, collaborative projects and custom sneakers, this artist is leaving her footprint on Seattle history.

The curator, gallerist and artist is resisting the art establishment with bold immersive experiments.

From intricate portraits to multistory murals, the artists bring Black history and bold color to the cityscape.

Through ceramics, sculpture, jewelry and public art, the multifaceted artist makes Black history tactile.

Thanks to our Sponsors

Your support helps Crosscut create projects like Black Arts Legacies. Learn how you can help with a one-time donation or recurring membership.

Support Crosscut