Watch: Debora Moore

A pioneer of glass techniques, this renowned creator is one of the few Black female artists in her medium.

As a direct connection to the Harlem Renaissance, this often overlooked painter inspired generations of Seattle movers and shakers.

by Jas Keimig / April 23, 2024

A young Black woman rendered in creamy tones of brown looks down and over her shoulder. She floats against a background of abstract blue, green and purple shapes, a pink shawl fluttering around her shoulders as her curly jet-black hair falls down her back, out of view. Her face is inscrutable. Is she gazing back at something sadly? Lost in her own dreams?

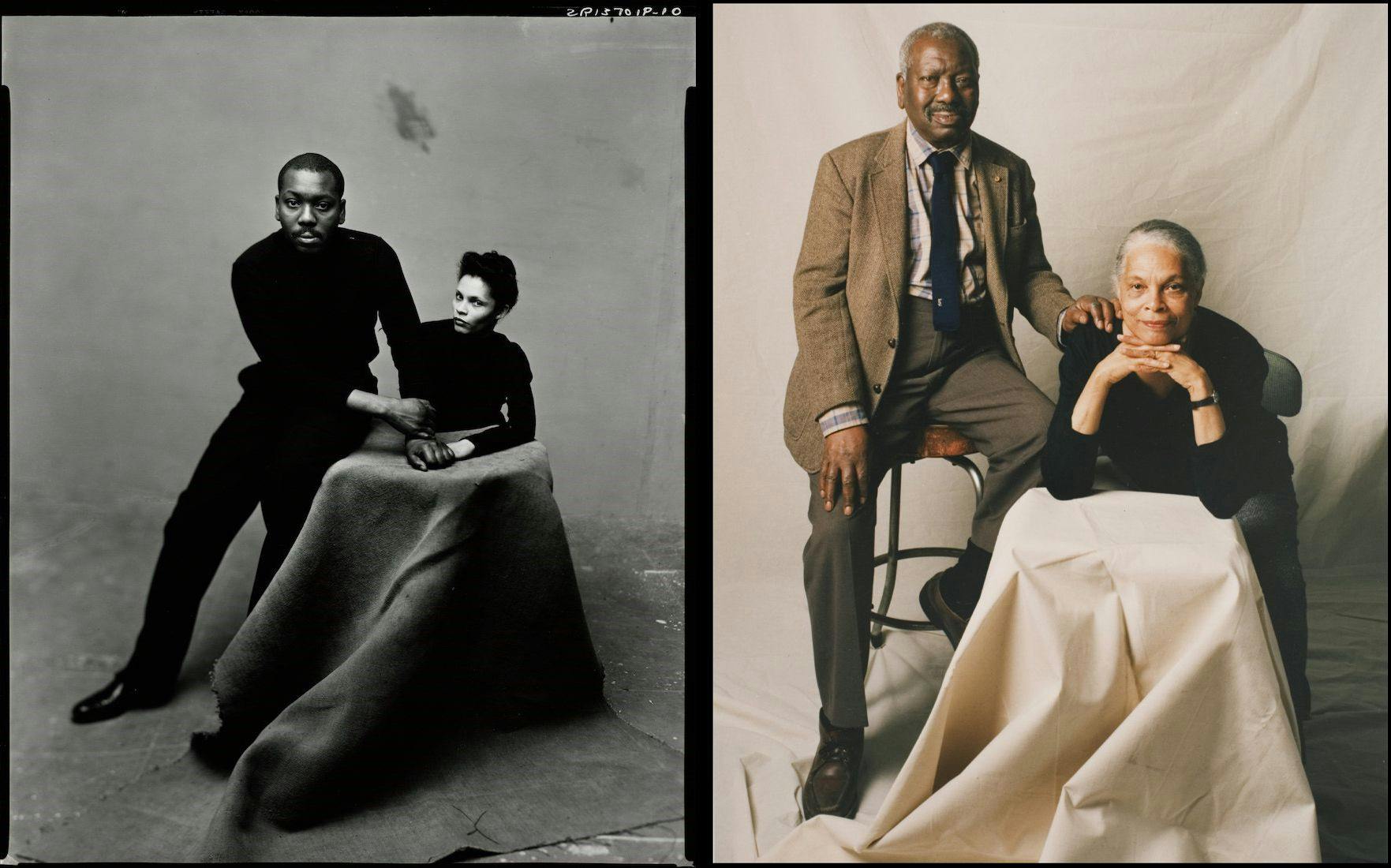

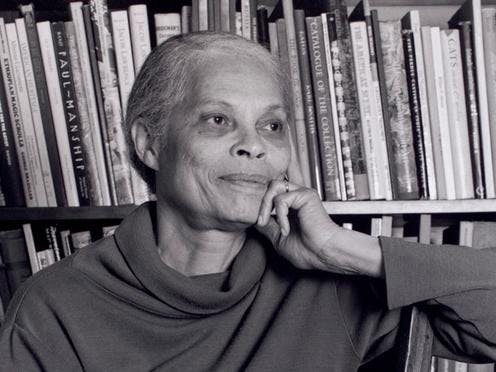

Distinctive cheekbones and a determined pout give away the identity of the young woman in this 1940 painting, “Portrait of a Girl.” She is the artist herself, Gwendolyn Knight Lawrence, at age 23. The emotional quality of this work — the gaze, the moody colors, the otherworldliness of its background — shows Knight’s signature attentiveness, the great care she afforded all of her subjects.

“I like to do portraits because I like faces,” she said in 1988. “When I do a portrait, I want to get the feeling of the person.”

Like her husband, legendary painter Jacob Lawrence, Knight’s long, storied career began in New York City during the Harlem Renaissance and ended in early 2000s Seattle. The couple landed here in 1971 after Lawrence accepted a tenured professorship at the University of Washington. Expecting to stay only a few years, Knight and Lawrence made Seattle their home for nearly three decades. They became fixtures in the city’s intellectual and cultural firmament, alongside the likes of playwright August Wilson and writer Charles Johnson, shaping generations of artists through their teaching and support of the city’s artist community.

While Lawrence’s immediate and universal acclaim launched him into the stratosphere early in his career, Knight’s years of consistent output — painting, print, sculpture — went largely overlooked in her lifetime, despite her immense impact on Seattle’s Black community. To Knight, though, her lack of recognition was simply a matter of attitude.

“I wasn’t really concerned with exterior motivation; it wasn’t necessary for me to have acclaim. I just knew that I wanted to do it, so I did it whenever I could,” she told African American literary magazine Callaloo Journal in 1988. “I guess my temperament is such that I don’t depend on outer stimulation. I like it — I like the support — I like it when people like what I’m doing. But even if they didn’t I wouldn’t simply say I’d stop, even though it would maybe be a little disappointing.”

Born in Bridgetown, Barbados, in 1913, Knight lived on the island until age 7. “I know that from the time I was a little child, I liked to do portraits,” she remembered to Callaloo. “I used to do portraits of everybody.”

In 1920, Knight’s widowed mother sent her to St. Louis, Mo., to live with close family friends. Six years later, Knight’s adoptive family moved to Harlem — the newly dubbed “Negro capital” — where the artistic renaissance was in full swing: Langston Hughes reflecting the Black experience in his poetry, Duke Ellington leading the house band at the bumping Cotton Club and kids Lindy Hopping the night away at The Savoy. Knight’s family lived in the Seventh Avenue building that also housed jazz greats Billy Strayhorn and Ethel Waters. As a lover of opera, dance and theater, Knight spent her teens immersed in the cultural activities of Harlem and New York City.

After graduating from Wadleigh High School — one of the city’s few integrated schools — in 1930, Knight attended Howard University. During her time there, she was taught and supported by the great painter Loïs Mailou Jones, whose joyful approach to color and empathetic portraiture no doubt influenced Knight’s work. Also a guiding force: influential graphic artist and printmaker James Lesesne Wells, whose bold and emotive prints often graced the cover of Black magazines.

But Knight was a woman and an artist, which meant most people at Howard did not take her seriously.

“Most people looked at women artists as if they were merely china painters or painters on velvet,” she reflected of the time. “So they weren’t really serious about pushing women artists. A woman artist would have to push herself and I haven’t that kind of temperament.”

Pressing financial concerns forced Knight to leave Howard after two years in 1932. Returning to Harlem, she found a new community in which she could flourish as an artist. She joined renowned sculptor Augusta Savage’s workshop, the Savage Studio of Arts and Crafts, where Savage helped nascent Black artists develop their artistic skills.

Savage’s studio became a home away from home for Knight. There, she brushed shoulders with the major Black artists of the time, including painter and sculptor Charles Alston, writer Claude McKay and poet Langston Hughes. A spirited and encouraging teacher, Savage took a liking to Knight and became her mentor. Knight later said Savage was “probably the strongest influence in my life as a visual artist.” (Savage even made a plaster bust of a young Knight in the mid-1930s; it’s in the permanent collection and currently on view at the Seattle Art Museum.)

And it was at the Harlem Community Arts Center in the mid-’30s where Knight met the love of her life, Lawrence — then a quiet, focused young painter with his eye on Black history. After years of friendship, they grew close and eventually married in 1941.

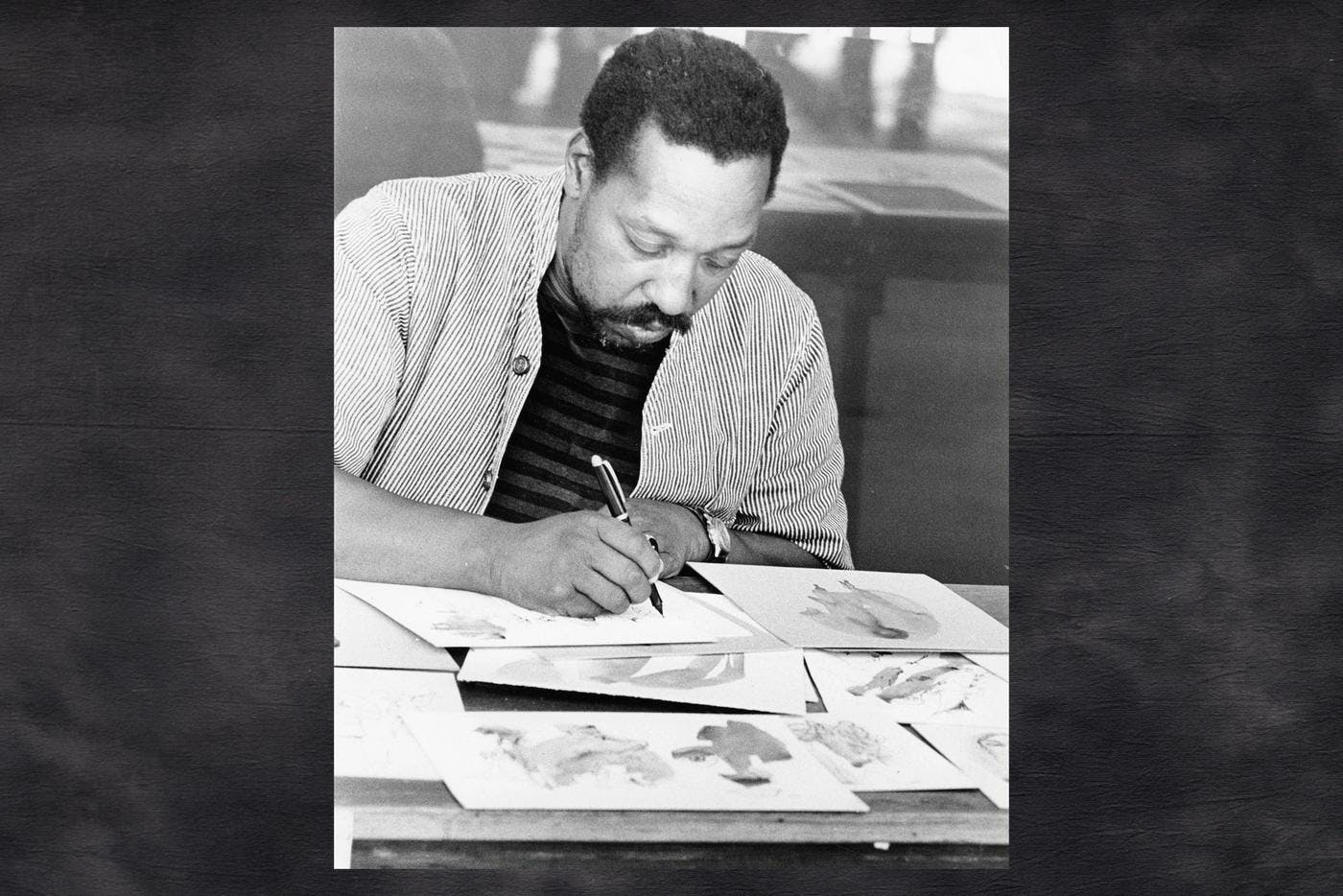

As artists, they supported and pushed one another. Their studios weren’t even that far apart: Lawrence painted in the kitchen while Knight painted in the bedroom. Both were figurative painters, but Lawrence focused on historical subjects like the Great Migration or the life of Haitian Revolutionary leader Toussaint Louverture while Knight consistently depicted her friends, dancers, horses and still lifes rendered in dreamy pastels.

“She’s very romantic in her painting, entirely different from me. Her feeling for color is very lyrical and her work has a certain kind of rhythm,” Lawrence said in a 1987 interview.

The first 30 years of their marriage brought lots of movement and growth. During the summer of 1946, Knight traveled with Lawrence to the socially progressive Black Mountain College in Asheville, N.C., at the invitation of prominent abstract artist Josef Albers. As a lover of dance, ballet especially, Knight had been studying movement in New York, learning Martha Graham’s technique from some of Graham’s dancers; Knight shared what she knew with the Black Mountain students while her husband taught art.

Back in NYC, she continued her arts studies: dance with the New Dance Group and design at The New School of Social Research. She then spent the 1950s working in Condé Nast’s library and magazine archives, giving the couple some financial stability as Lawrence mainly held temporary teaching positions. Lawrence’s artistic career was gaining momentum and Knight focused on supporting her husband’s work over her own.

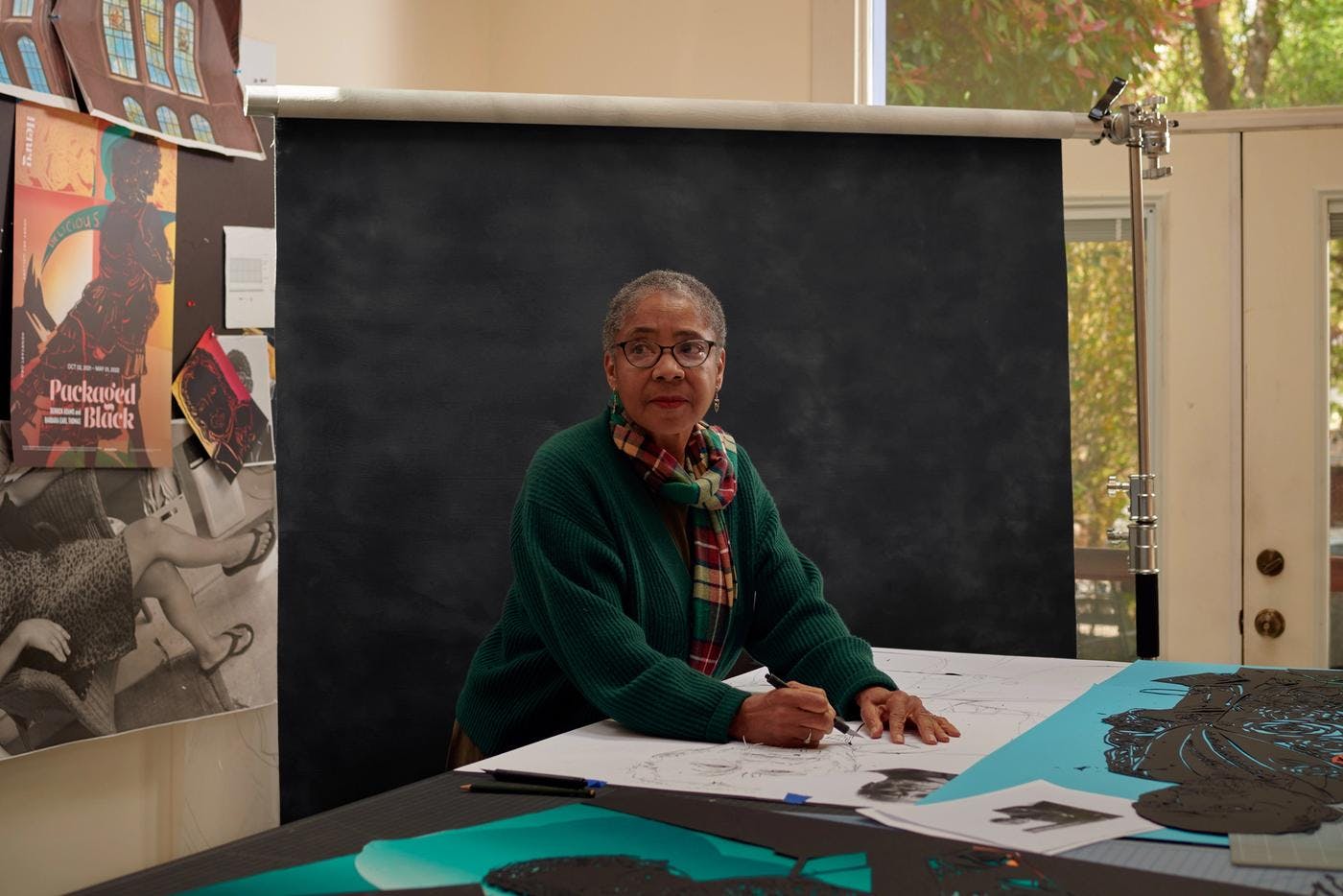

“Gwen never, ever thought of herself as being in a position where she was not respected,” says Seattle artist Barbara Earl Thomas, a close friend of the couple. “She just said plainly it was hard enough for one person to make it and both people had to be in service of one of them making it. So that’s what she did.”

After an influential sojourn in Nigeria in the mid-’60s and another five or six years in New York City, the couple headed west in 1971 for the mossy promises of Seattle.

As Lawrence took on his professorship at the University of Washington and they settled into a house in Laurelhurst, Knight had more time to create work — warm portraits of Augusta Savage, expressive still lifes of African masks, energetic black-and-white monoprints. Thomas, who met Knight as a UW college student, remembers, “She never had huge amounts of work, but she always had a constant flow of work.”

Respected art dealer Francine Seders represented and routinely showed Knight’s work (along with that of other UW art professors and their wives) at her gallery on Greenwood Avenue.

“I admire her grace and style, her assurance and independence,” Seders wrote in a catalog of Knight’s 1988 exhibition at the Virginia Lacy Jones Gallery in Atlanta. “These traits are apparent in her work – she paints what she wants in the way she wants without reference to current trends.”

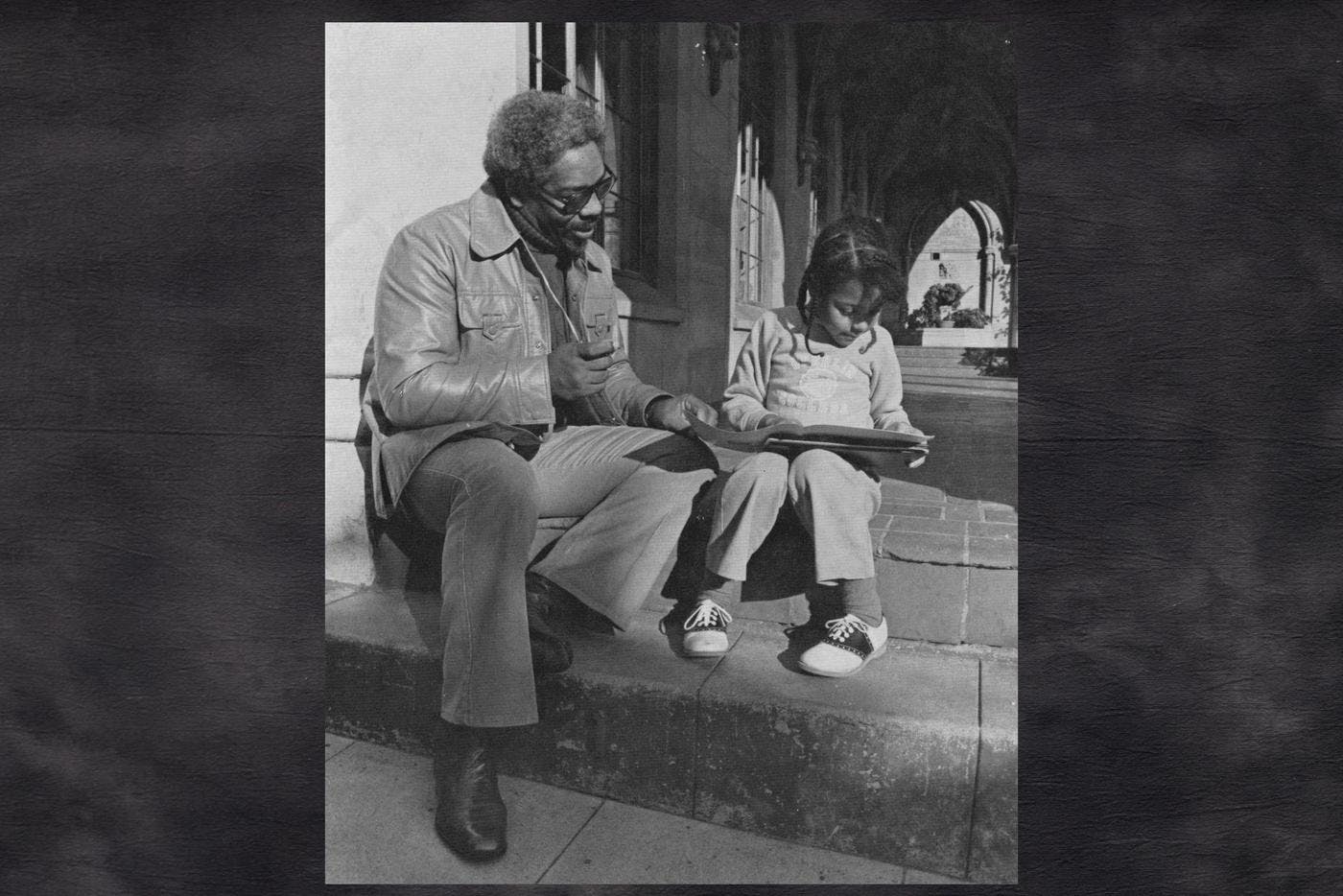

Because both Knight and Lawrence’s art careers were so profoundly shaped by their mentor Augusta Savage, they knew the importance community played in lifting up artists of all backgrounds. Both Knight and Lawrence were heavily involved in the arts community in Seattle. They showed their work at the Urban League’s art shows, popped up on juries both large and small, and even spoke with grade schoolers about art.

“They were always supportive of anybody who was doing anything,” Thomas says. Knight took her civic duties seriously and served on the King County Arts Commission, the Urban League and the Seattle Chapter of the Links, a nonprofit run by and for women of African descent.

Knight and Lawrence spent as much time as they could holding up artists through their service and instruction, but often it was the fact of these two giants of the Harlem Renaissance simply being here that grounded Black artists in Seattle.

“They lived history in a way that I’ve only read about,” Micki Flowers, groundbreaking KIRO journalist and friend of Knight and Lawrence, recalls. “It was an amazing thing to be able to sit down, have a conversation and hear history firsthand.”

After Lawrence died in 2000, Thomas and other community members collaborated to put on a giant solo exhibition of Knight’s work: the 2003 show Never Late for Heaven at the Tacoma Art Museum, which included decades’ worth of Knight’s paintings and prints and came with a catalog of essays by Thomas and curator Sheryl Conkelton.

“[Knight] was appreciative and she liked it, but it wasn’t what made her life. Her life was already made,” Thomas says. “It was something I felt was very important that she have before she died. And I think it was probably more interesting for me than it might have been to her.”

When Knight died in 2005 at age 92, Seattle lost an important connection to the past. Although Knight’s work was never as widely exhibited or seen as Lawrence’s, her legacy is more nuanced than “woman artist overshadowed by husband’s career.” Knight and Lawrence were a unit and built each other up — one’s work was not possible without the other’s total support and care.

“Their love affair, their marriage was so tight it was a beautiful thing to see. There was no competitiveness, no anger. They co-lifted each other,” reflects Dr. Constance Rice, Seattle Art Museum’s current board chair. “I would go to U Village, drive out to 24th Avenue Northeast and see the two of them standing hand in hand waiting for a bus.”

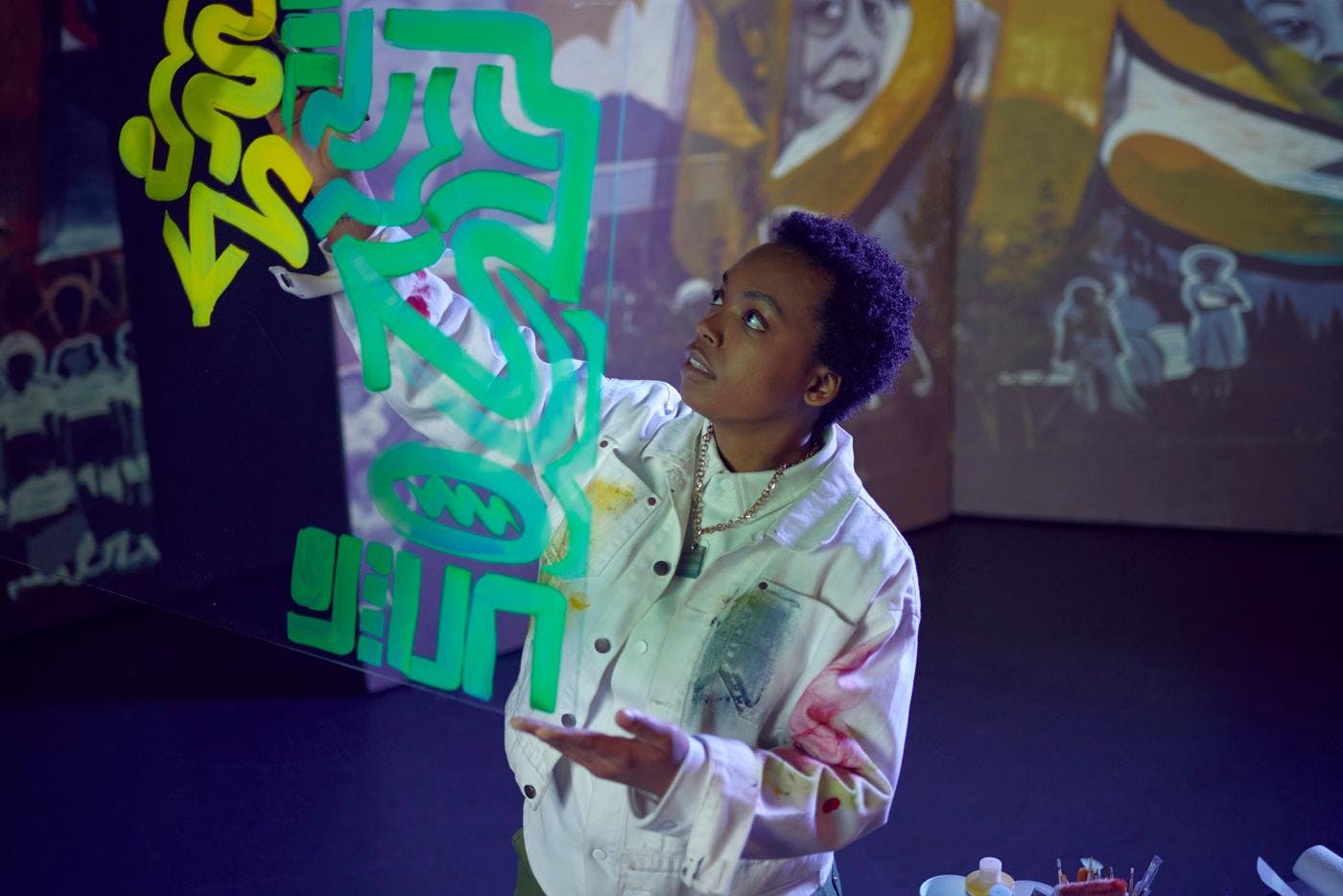

Concrete examples of the legacy Knight leaves in Seattle include SAM’s Jacob Lawrence and Gwendolyn Knight Prize, given biannually to an early-career Black artist (including recent recipients Lauren Halsey and Aaron Fowler). But in the lives Knight directly touched, her and her husband’s spirit and influence continues in the work ethic and groundedness of artists and other community members’ approach to doing generative work.

“What they showed me was that you work regardless. You make [something] and people think it’s wonderful — great,” says Thomas. “But if you’re not working and you’re not demonstrating this privilege that you have of creating, then you’re missing the boat.”

Black Arts Legacies Season 3 is made possible in part thanks to support from 4Culture.

Black Arts Legacies Writer

ARTIST OVERVIEW

Painter, visual artist

(1913–2005)

A pioneer of glass techniques, this renowned creator is one of the few Black female artists in her medium.

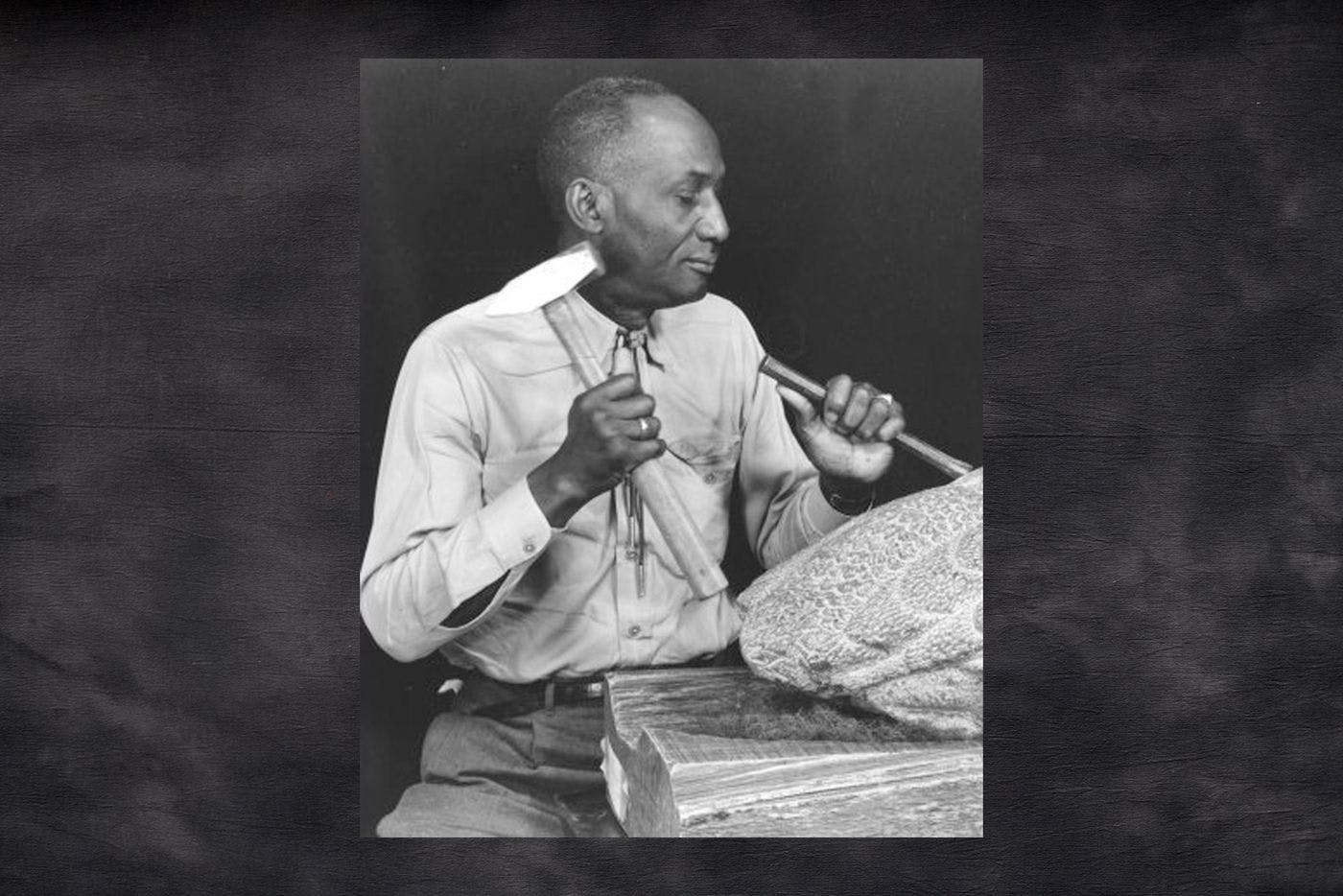

An influential member of the noted Northwest School, the Central District sculptor turned his home into a community center for artists.

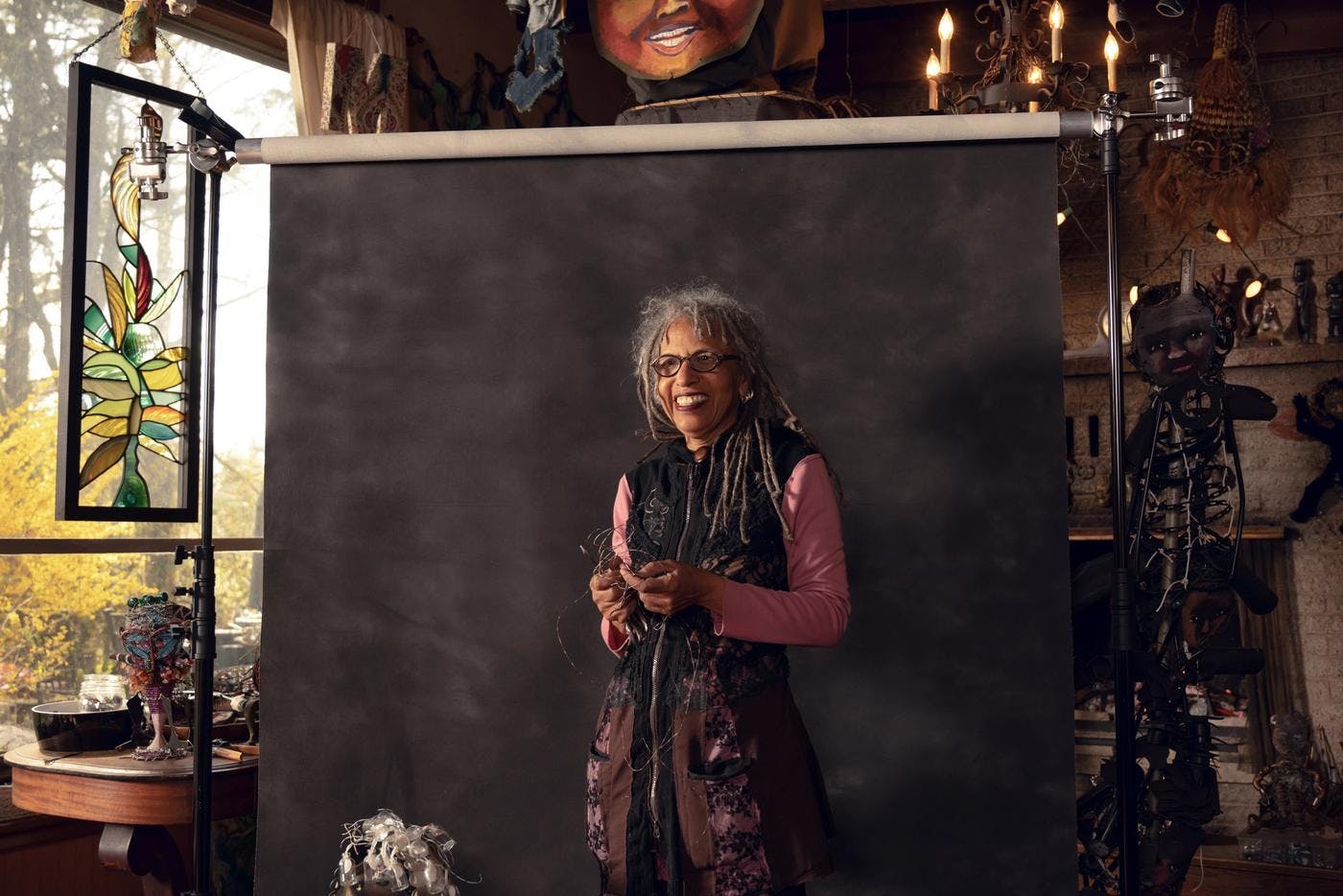

Salvaging old cloth and scrap metal, the longtime Seattle sculptor finds beauty in what’s discarded.

This Seattle artist channels his personal history and activism into vibrant murals and abstract paintings.

With meticulous skill and a communal approach, the longtime Seattle artist has cut her own path.

The first Black art instructor in Washington was an experimental artist ahead of his time.

Two curators separated by decades turn homes into galleries to support artists.

The influential art teacher uses books, found objects and photography to provoke thought and shift perception.

The late couple's house is now a cultural center that inspires the next generation.

The late director, producer, stuntman and teacher used film and video production to lift up the voices of Seattle’s Black community.

Through public murals, collaborative projects and custom sneakers, this artist is leaving her footprint on Seattle history.

Born and raised in Seattle, this self-taught photographer captured Black life in the city for much of the 20th century.

The curator, gallerist and artist is resisting the art establishment with bold immersive experiments.

From intricate portraits to multistory murals, the artists bring Black history and bold color to the cityscape.

Through ceramics, sculpture, jewelry and public art, the multifaceted artist makes Black history tactile.

Thanks to our Sponsors

Your support helps Crosscut create projects like Black Arts Legacies. Learn how you can help with a one-time donation or recurring membership.

Support CrosscutLoading...