Julian Priester

A fount of knowledge for the jazz community, the trombonist and living legend is shaping the next generation of Seattle musicians.

Composing meditative music with a looping pedal, this Seattle cellist has charted her own sonic path.

by Jas Keimig / May 21, 2024

Barefoot, Gretchen Yanover sits alone on stage with a looping pedal, sheet music and a microphone before her. A thoughtful silence fills the air of the Langston Hughes Performing Arts Institute as she readies the neck of a slim electric cello on her shoulder, raises her bow and begins to play. Solemn, yawning sounds erupt from her instrument. Slowly, she layers them into loops using her pedal, then lays a bright, effervescent melody on top — creating a symphony of one.

Fans and friends packed the house on this sunny spring afternoon in support of Yanover’s fifth and most recent album, Holding/Movement. Deeply inspired by the work of Seattle poets, Yanover turned lines from their poems into songs, giving their words her own contemplative spin in 10 instrumental tracks.

In “This Four-Walled Pasture,” Yanover echoes the melancholic rumination in Luther Hughes’ poem “Mercy” with a plucky, deliberate tenderness. In “At the End of Reason, I Am Locked in Place,” she draws from Quenton Baker’s “Dialectic,” transforming the poet’s claustrophobic and violent language into a tense, emotional composition. Other songs take their inspiration from works by Jourdan Imani Keith and Ally Ang.

The connection with local artists extends to the album’s cover. It’s a portrait of Yanover by artist Barbara Earl Thomas called “My Lady of the Cello,” originally made for Thomas’ 2022 show of large-scale portraits centered on creativity and the human body. Thomas first heard Yanover play at Seattle-Tacoma International Airport, where since 2014 the cellist has been on the roster of the live music program, playing tunes for weary travelers in the main concourse.

Thomas remembers the moment clearly: “There in the middle of the walkway was this beautiful person playing a cello. She seemed to be cloaked in the sound of her own music unbothered by the passersby. I stopped, listened and was made better for it. I left some money in her case and moved on,” Thomas wrote in a recent email. “When I returned maybe a week later, I entered the walkway and moved toward baggage claim, there she was again. Almost right where I left her! Still quietly playing her cello. The crowd moved around her as though she was a burnished stone in the middle of a river.”

For nearly 40 years, Yanover has dedicated herself to the art of the cello, composing ambient music for her solo work and playing in more classical modes with an orchestra. Her devotion to her craft has led her to chart her own path as a rare Black classical musician, as a cellist who dabbles in electronic music and as a composer with a bevy of collaborators.

To wit: In 2020, Yanover invited University of Washington dance teacher Noelle Price-Bracey to perform alongside her at a TedX talk. In 2019, she composed the soundtrack for the film Space Needle: A Hidden History, about how dancer Syvilla Fort may have influenced the design of the iconic Seattle structure. (Yanover’s swelling original music is layered with the sound of Jourdan Imani Keith’s voice reading a poem inspired by Fort and visuals of Nia-Amina Minor dancing.)

And last year, Pacific Northwest Ballet soloist Amanda Morgan choreographed several of Yanover’s pieces for the PNB Professional Division students, and Yanover performed one of those pieces with the students onstage at McCaw Hall.

“It has only been in the last decade that I feel like I’ve found connections and been embraced by the Black arts community,” Yanover reflects a few days after her concert. “I think there weren’t enough Black artist types to connect with in my younger days in Seattle.”

Born in 1972 and raised in Seattle’s Maple Leaf neighborhood, Yanover first picked up the cello as a sixth grader, when her parents signed her up for a beginning strings class at Eckstein Middle School in Greenwood. At her first lesson, she sat next to the only other Black student. “Everyone wanted to play violin,” Yanover remembers. “I didn’t want to be like everyone else.” Then the teacher asked both her and the student beside her if they wanted to play cello. The kid next to her nodded; Yanover followed, in solidarity.

“I did not actually know what a cello was,” Yanover admits, adding that she’d probably seen one on trips to the Seattle Symphony with her father and siblings.

But when she brought that first cello home, she was hooked. “It made an addicting sound,” she says. “With the cello, you rest it on your heart. I wanted to make sounds all the time. I would pluck it. We didn’t even use bows at the very beginning. I was very excited and became very obsessed.”

Yanover’s cello obsession carried her throughout middle and high school, as she immersed herself in classical music like Bach’s Suites for unaccompanied cello. When she matriculated at the University of Washington, she continued on her classical-music journey, graduating with a B.A. in musical education and performance in 1994. Then, after working on an education project for a year and a half, Yanover went back to UW and received her teaching certificate in 1998. She expected to spend most of her career in front of students, but her expectations changed almost immediately.

“The very first day that I taught at Meany Middle School, I also — later that morning — went and auditioned for Northwest Sinfonietta Orchestra, a regional chamber,” she recounts. She got the gig. “I actually started my professional classical music life and my school teaching career on the same day.”

As she balanced these two careers, Yanover also looked for ways to collaborate with other musicians. Since college, she’d experimented with cello in various genres. (Mainstream interest in the instrument had spiked during the mid-1990s following Seattle cellist Lori Goldston’s appearance on Nirvana’s iconic MTV Unplugged session.) In 1994, Yanover recorded and performed in Seattle with indie band Built to Spill on their There’s Nothing Wrong with Love album. Three years later, she played at the Seattle stop of k.d. lang’s orchestral tour.

But playing in an electrified band with an acoustic instrument was a “nightmare,” Yanover says, explaining that drums and amps make the cello’s strings vibrate, causing static-y feedback. Frustrated, she picked up an electric cello for the very first time in 2001.

That solved the feedback problem, but the real revelation came when Seattle trumpeter Chris C.D. Littlefield encouraged Yanover to try experimenting with different pedals. The Line 6 pedal proved transformative. It opened up a whole new world of layered sound.

“As a cellist, it’s not impossible to play chords, but we’re not really a chordal instrument the way a piano or a guitar is,” she says. “So being able to create my own harmonies and accompaniments in real time was totally mind-blowing.”

The looping pedal is integral to Yanover’s composing practice. She’s currently using the Boss RC-1, which not only helps her build her own harmonic accompaniment, it also suits her thoughtful, deliberate approach to musical composition. Looping allows her to improvise more easily and take her time constructing the various facets of a musical landscape.

“I marinate, not always on the cello,” Yanover says. “I might get some musical phrase stuck in my mind and I’ll wake up in the middle of the night and do a voice memo.”

Yanover calls herself a “slion” — a term her daughter made up, meaning “part snail, part lion.” “[A slion] is slow and powerful,” Yanover explains. “I know there’s people who can just pop stuff out, and it flows out of them quickly. But I’m on Tortoise Road.”

That pensive deliberation with the looping pedal informed her debut solo album, Bow and Cello, which she released in 2005 in the face of great personal tragedy: the death of her brother in a house fire. In the midst of her grief, Yanover says she quit nearly everything (except the orchestra) and cast her album to the wayside.

But her partner at the time picked up the pieces. “He got a graphic designer, he sent [the album] out to press, he made cover letters and sent the album to radio stations,” she says. “Because he planted all these seeds, that album kept having a little life of its own. It took me out of my hibernation.”

Yanover continued to teach music classes and perform with the NW Sinfonietta, but it would be nearly 10 years before she released her second album, Waves Wash Over Us, in 2014. It took a lot of encouragement from people like Steve Peters of the Chapel Performance Space and pianist Rachel Grimes, who rallied around her work. “I was terrified but I finally was ready to do it,” she said.

The mid-2010s marked a major shift in Yanover’s career trajectory. Requests for her solo work started to roll in, making it difficult to juggle teaching and playing. In 2015, Yanover gave up teaching completely to work as a full-time musician.

Her schedule has been jam-packed ever since. She’s composed and performed with LeVar Burton on the Seattle stop of his 2018 LeVar Reads Live tour (“a career highlight,” she says), served as an artist-in-residence with Shunpike in 2020 and Town Hall in 2021 and received composition commissions from the Seattle Symphony, Seattle Pacific University, and the University of Oregon. She also released three more albums: 2017’s Bridge Across Sound, 2020’s Cello Glow (a Christmas album!) and 2024’s Holding/Movement.

Along the way, Yanover’s collaborations also expanded. Her work with poets began after she met local writer Reagan Jackson at a performance in the Tri-Cities and composed a piece based on Jackson’s poem “On Being Black and a Butterfly.” And that appreciation wasn’t a one-way street — Jackson also felt moved by their connection. “It was phenomenal to have the opportunity to hear that energy translated through her body and through her cello,” says Jackson. “It gave me chills.”

Yanover’s ability to channel external energy into music is exemplified by one of her many regular gigs — playing at SeaTac.

For her 2024 song “Bisoux,” Yanover drew on that experience, inspired by the airport’s boisterous noises and sounds. The piece loops one note to resemble the beeping of tiny carts zooming up and down the hallways at Sea-Tac, which Yanover overlays with wispy, wistful melodies that recall the transience of the airport. It embodies what makes her music so distinctive, its recurrent themes mimicking the cyclical nature of life.

“My music can be meditative,” she reflects. “It has this continual circling around.”

Black Arts Legacies Season 3 is made possible in part thanks to support from 4Culture.

Black Arts Legacies Writer

A fount of knowledge for the jazz community, the trombonist and living legend is shaping the next generation of Seattle musicians.

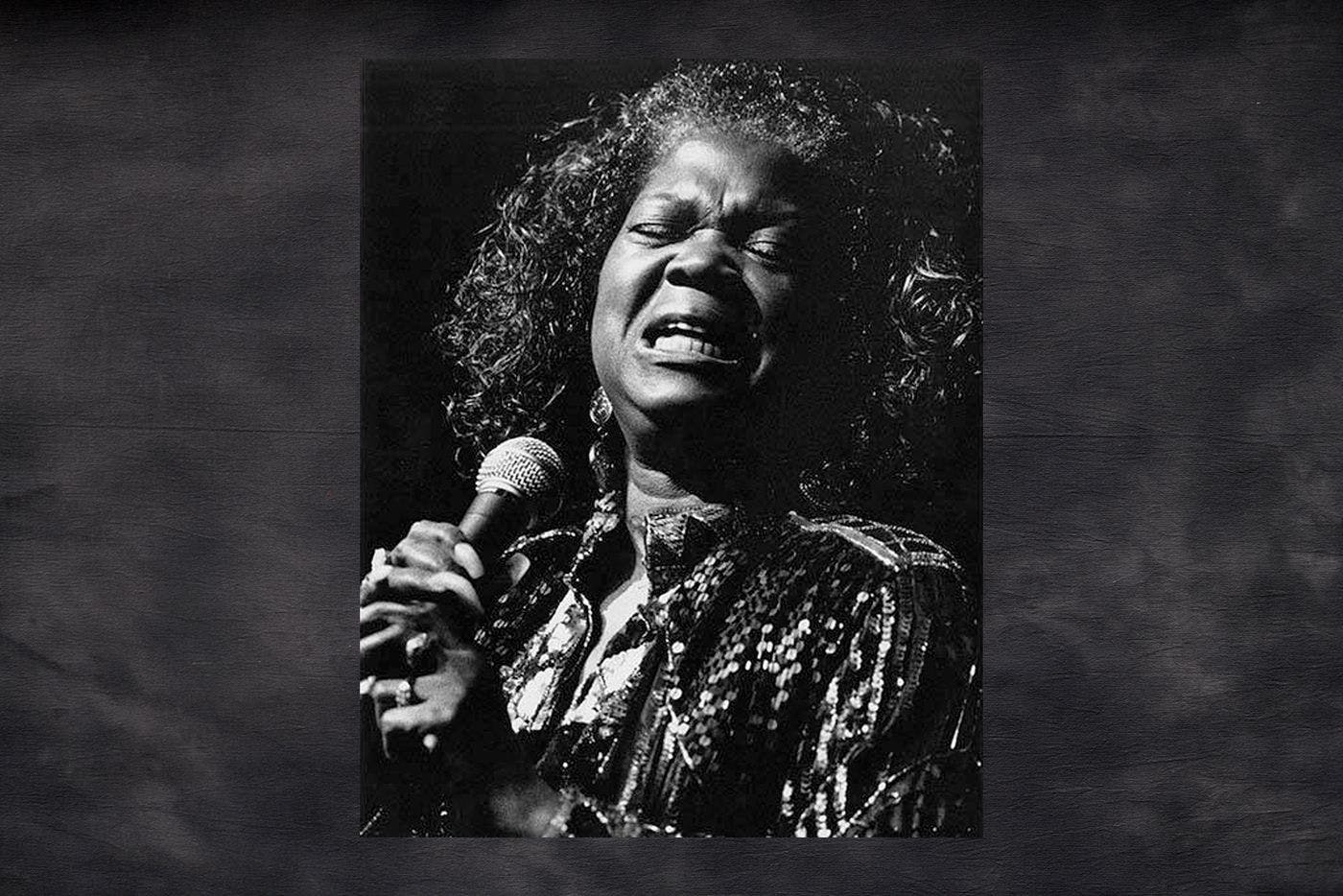

With a voice like ‘honey at dusk,’ the singer helped put Seattle’s early jazz and blues scene on the map.

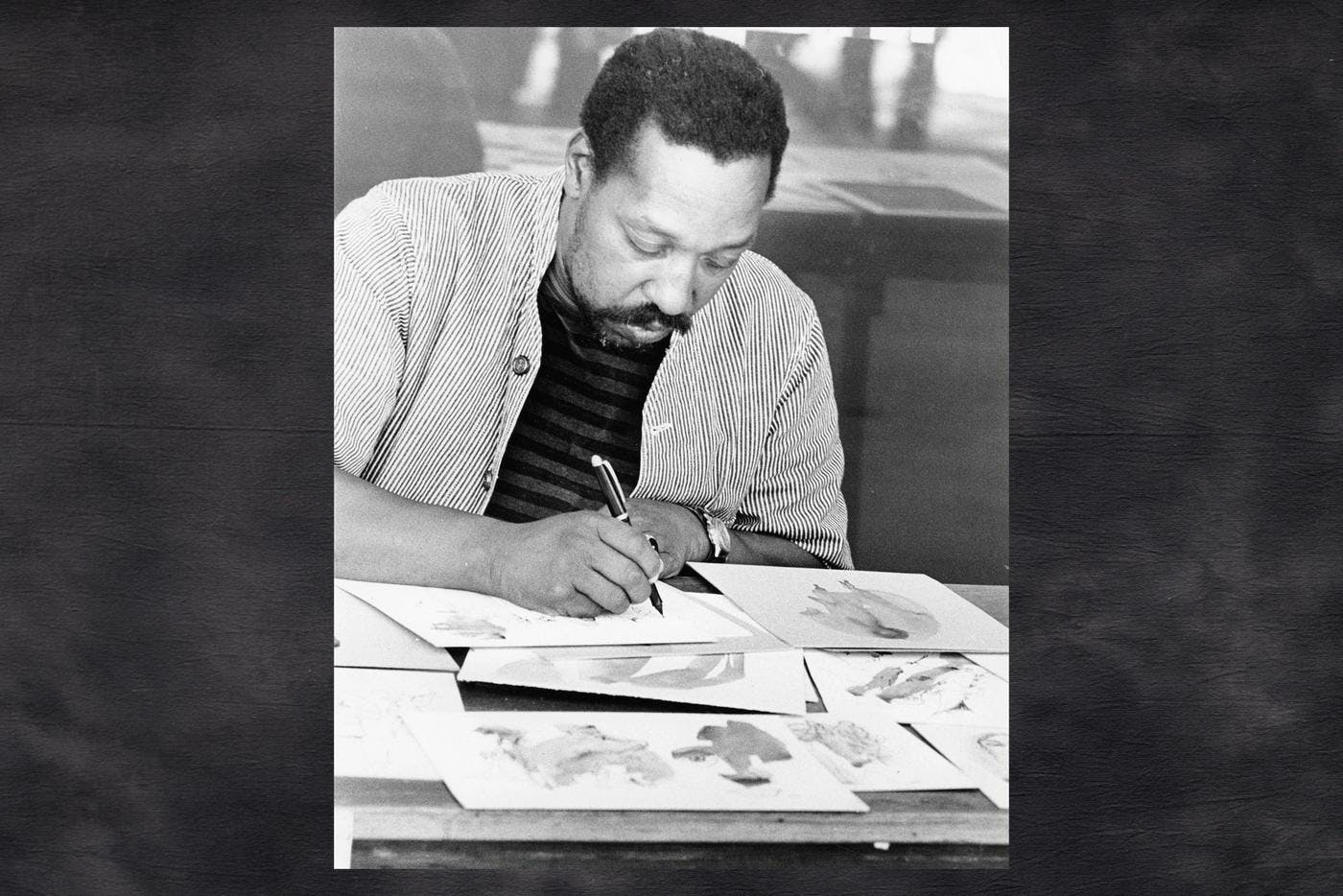

The first Black art instructor in Washington was an experimental artist ahead of his time.

For three decades, this Seattle DJ electrified the airwaves, paving the way for future Black radio personalities.

A poet at heart, this soul singer/songwriter is inspiring the next generation of Seattle musicians.

As a founder of Digable Planets and Shabazz Palaces, the Seattle rapper has pushed hip-hop to the outer limits.

The Seattle rapper keeps his memories of the Central District alive with vivid lyrics and a jazz sensibility.

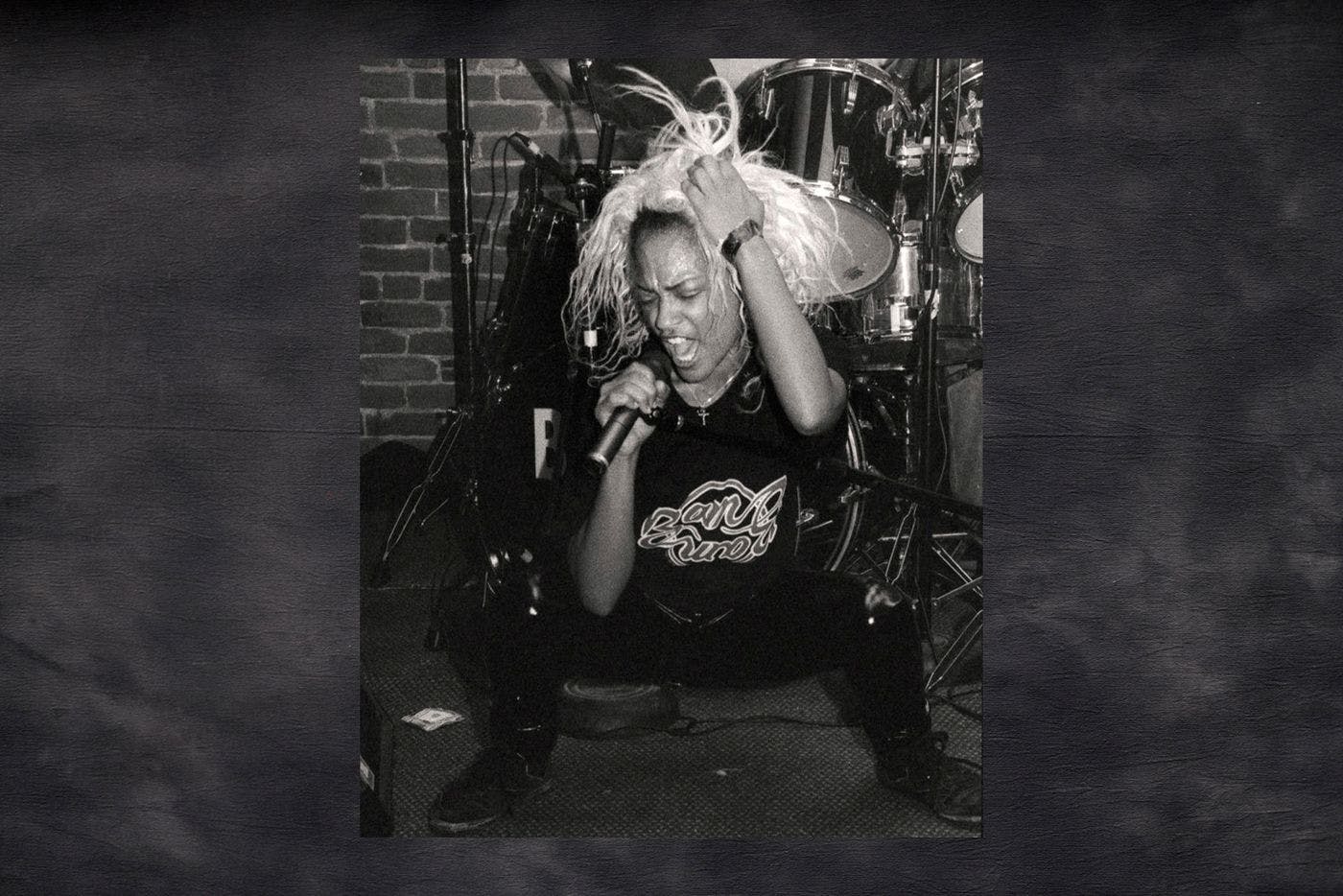

A pivotal figure in Seattle’s proto-grunge scene, the Bam Bam singer has been long-overlooked. Now, rock history is being rewritten.

The talented multi-instrumentalist uses music to string communities together.

Meet a Seattle music pioneer and the band carrying the legacy of Northwest rock forward.

This beloved Seattle DJ found his divine calling in music — and in sharing it with others.

Thanks to our Sponsors

Your support helps Crosscut create projects like Black Arts Legacies. Learn how you can help with a one-time donation or recurring membership.

Support Crosscut