Julian Priester

A fount of knowledge for the jazz community, the trombonist and living legend is shaping the next generation of Seattle musicians.

The talented multi-instrumentalist uses music to string communities together.

by Jas Keimig / May 23, 2023

On a sunny spring afternoon, a group of Seattleites packed into the Central District home-turned-arts space Wa Na Wari to catch the final act of Berette Macaulay’s roving performance, UN-[TITLED].

As three dancers twirled around the wood-floored living room, Benjamin Hunter sat off to the side watching them bend and sway through the space. Alternating between a guitar and a violin, the Seattle musician strummed in perfect harmony with the performers, their movement and his pensive music in conversation.

“My favorite way of making art is in collaboration with other folks who know music is only made richer with dance,” Hunter says later in a phone interview. “They go hand in hand.”

Since moving to Seattle more than 15 years ago, Hunter has used music to build space and community for local artists of many genres. And boy, has he been busy.

Hunter has built a robust solo practice as a violinist, string player and composer, performing and writing pieces for works like UN-[TITLED] and choreographer Dani Tirrell’s celebrated Black Bois.

He’s toured the globe with Joe Seamons as half of a roots-music duo; founded and directed multiple community-focused arts organizations and spaces; was artist-in-residence at On the Boards in 2020-2021; and currently serves as artistic director of Northwest Folklife.

In every role, Hunter remains focused on building the Seattle arts scene in an ambitious and holistic way.

“[My connection] just keeps getting deeper and deeper. You meet more people and you are connected to more of the community,” he says. “As somebody that didn't grow up here — and I think there's quite a few of us Black folks that didn't grow up here — Seattle is my home now.”

Born in Lesotho, Hunter spent his childhood in locales from Phoenix, Arizona, to Harare, Zimbabwe. “My mom valued travel more than anything,” he says. “I think it’s guided a lot of the work that I do as an adult.”

At age 5, Hunter picked up the violin, and the instrument has since accompanied him to whatever corner of the world he has found himself in. His globe-trotting youth informed the music he felt drawn to: oldies and Motown CDs his mother put on in the car; mariachi and Central American tunes played around Phoenix; the sounds and rhythms of performances by West African musicians at the university in Zimbabwe where his mom worked.

I want to be inspired by it all — past, present and future.”

“It’s not just the music, it was the architecture, it was the pace of different cities, it was the food,” he says. “All of the things that converge which influence each other. I could see all the intersections so clearly when put into a world, non-monolithic perspective.”

He received a degree in violin performance from Whitman College in Walla Walla on a full-ride scholarship, but nurtured a love for music found outside of academic and fine-art institutions. The kind of music that’s played in community with other people and in accordance with their culture. That plucky, multitudinous word: folk.

“To me, folk is everything,” says Hunter, now 38. “Hip hop is folk, classical is folk. Whatever, wherever people find community, and an opportunity to share and shape an identity with people around you, I think, is folk.”

After college, Hunter wanted to find more freedom and fluidity in his musical practice. “One of the hardships for classical musicians is breaking away from the stranglehold of reading what’s on the page,” he says. He followed that impulse to Seattle in 2007 and sought jam sessions where he could play his violin — most of which were devoted to bluegrass and old-time music.

Diving into the rollicking strains of string-band music opened Hunter to the lineage of the violin in American music. At festivals like Fiddle Tunes and the Acoustic Blues Festival, hosted by Centrum in Port Townsend, Hunter connected with even more musicians and genres: the blues, ragtime, traditional jazz, string band and vaudeville. The experience proved crucial to his formation as an artist.

“[Centrum] really helped open my eyes to the possibilities of violin and, ultimately, my style of music,” Hunter says. “I had to create my own sound.”

Built on a soulful singing voice and deft, energetic fiddle-playing across genres, his mellifluous sound has propelled his music career. It has taken him to places like Cuba, as part of a cultural-exchange delegation of Seattle musicians, and the TEDx stage, where he played and spoke to the communal power of folk.

And Hunter not only talks the talk of community, he walks the walk, working to build ambitious arts collaborations in Seattle.

In 2011 he launched Community Arts Create, an organization dedicated to bringing artists together across cultures and generations to make art for art’s sake, be it mural painting, music performances, even cooking experiences. “I wanted to create a space that looked at shared experiences, collective achievement and how to bring people together through their inherent connection to artists.”

Finding a physical home for Community Arts Create led him to his next project, the Hillman City Collaboratory, a “social change incubator” dreamed into reality by Hunter and co-founder John Helmiere in 2013.

Since the beginning, HCC served many purposes: a co-working space, an event and art-show venue, a performance space, a business hub, a spot for the community to gather and use however it needed to.

After making it through the height of the pandemic by the skin of their teeth, Hunter and his partners were forced to permanently close the HCC in 2021 after the building’s landlord raised the rent. Although Hunter and Helmiere were able to fundraise enough money to buy the building, they were unable to reach an agreement with the property owner. “It really was a unique place,” laments Hunter.

In the present, Community Arts Create operates in a much more low-key fashion, acting as what Hunter calls a “clandestine arts investor advocate,” dispensing funding to arts organizations and artists that need it rather than programming their own events. Despite losing the Collaboratory as a gathering hub, Hunter’s work in the community continues to build on itself, particularly as it uplifts Black and brown communities in Seattle.

That’s what led him on the now-seven-year journey of opening Black & Tan Hall in Columbia City with co-founders Tarik Abdullah and Rodney Herold.

Naming it in tribute to the historic Black & Tan Club, a popular integrated jazz club in Chinatown-International District that operated from 1922 to 1966, Hunter and his co-founders conceived the cooperative as an opportunity to center community needs and challenge the neighborhood’s gentrification.

“Since I have known him, Ben has been about collaboration and making sure that people are in the room to bring not only art forward, but humanity,” says choreographer Dani Tirrell, who worked with Hunter on Tirrell’s Seattle-produced dance piece Black Bois.

Tirrell says Hunter’s efforts to bring Black and Tan Hall to life speak to “his investment in making sure people have a space to gather in Seattle and to also make sure displacement does not happen.”

In conceiving the Black & Tan project, Hunter felt particularly animated by Seattle’s history of Black radicalism and liberation movements, especially in how Black artists reflected those ideas.

“Jimi spoke about this [history] in his music, and it was definitely front and center in his playing. Tina Bell exemplified that in her sound. Barbara Earl Thomas and Valerie Curtis Newton are doing it with visual art and theater,” says Hunter.

“To me, it's not just the music,” he adds. “It’s the entire culture. Which is why I find myself tentacled to so many things, because it’s all connected and I want to be inspired by it all — past, present and future.”

While Hunter is staying mum on when exactly Black & Tan will open — there have been a lot of legal and building hoops to jump through since the journey began in 2016, and he doesn’t want to speak too soon — he’s clear about its aims.

“I'm not gonna buy it, flip it, sell it,” he says. “Rather, I'm gonna nurture it, care for it, and steward it.”

That sense of stewardship also permeates his work as Northwest Folklife’s artistic director, a role he stepped into in 2021. Alongside his longtime friend and managing director Reese Tanimura, Hunter advocates for a robust creative ecosystem in the city.

“It’s really good to have somebody who’s willing to reach for the stars,” Tanimura says of working with Hunter. “He brings deep personal connections to people in the community and a willingness to make more of those connections.”

Hunter hopes to help Folklife “stretch its legs as an organization that’s more than just a festival” and to partner with organizations and businesses beyond the Seattle Center Campus for more year-round programming.

Part of that work includes shifting the popular understanding of “folk” away from the white hippie stereotype and toward his expansive definition, which includes more genres, more communities and more understanding of how people come together around music.

“There's a lot of preconceptions about what folk [music] is… that has prevented [certain] communities from participating or engaging in Folklife,” Hunter says. “One of my big missions is to knock down, in whatever way I can, that stigma so that we can make the concept and definition of folk something that is a lot more inclusive and inviting.”

Black Arts Legacies Writer

A fount of knowledge for the jazz community, the trombonist and living legend is shaping the next generation of Seattle musicians.

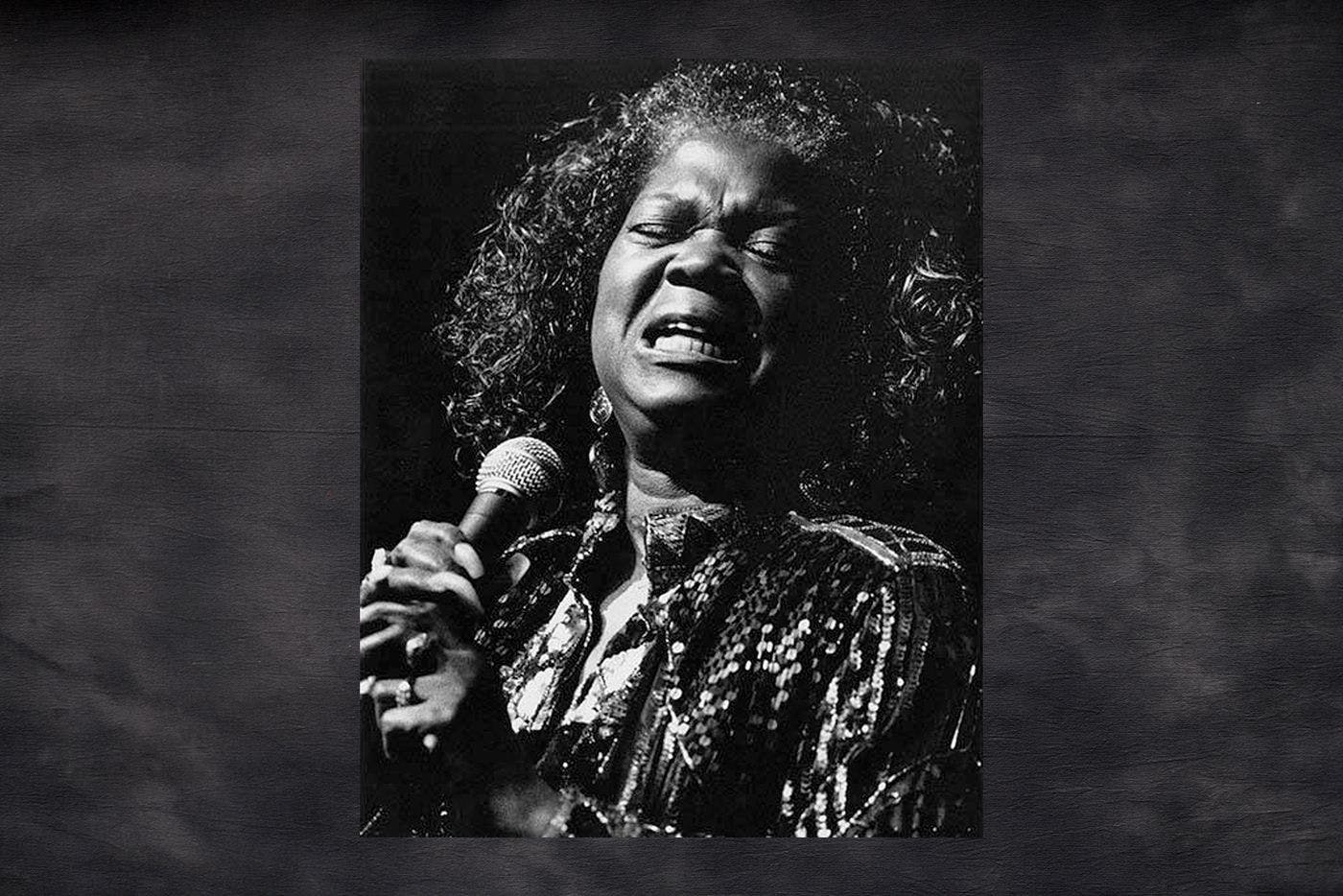

With a voice like ‘honey at dusk,’ the singer helped put Seattle’s early jazz and blues scene on the map.

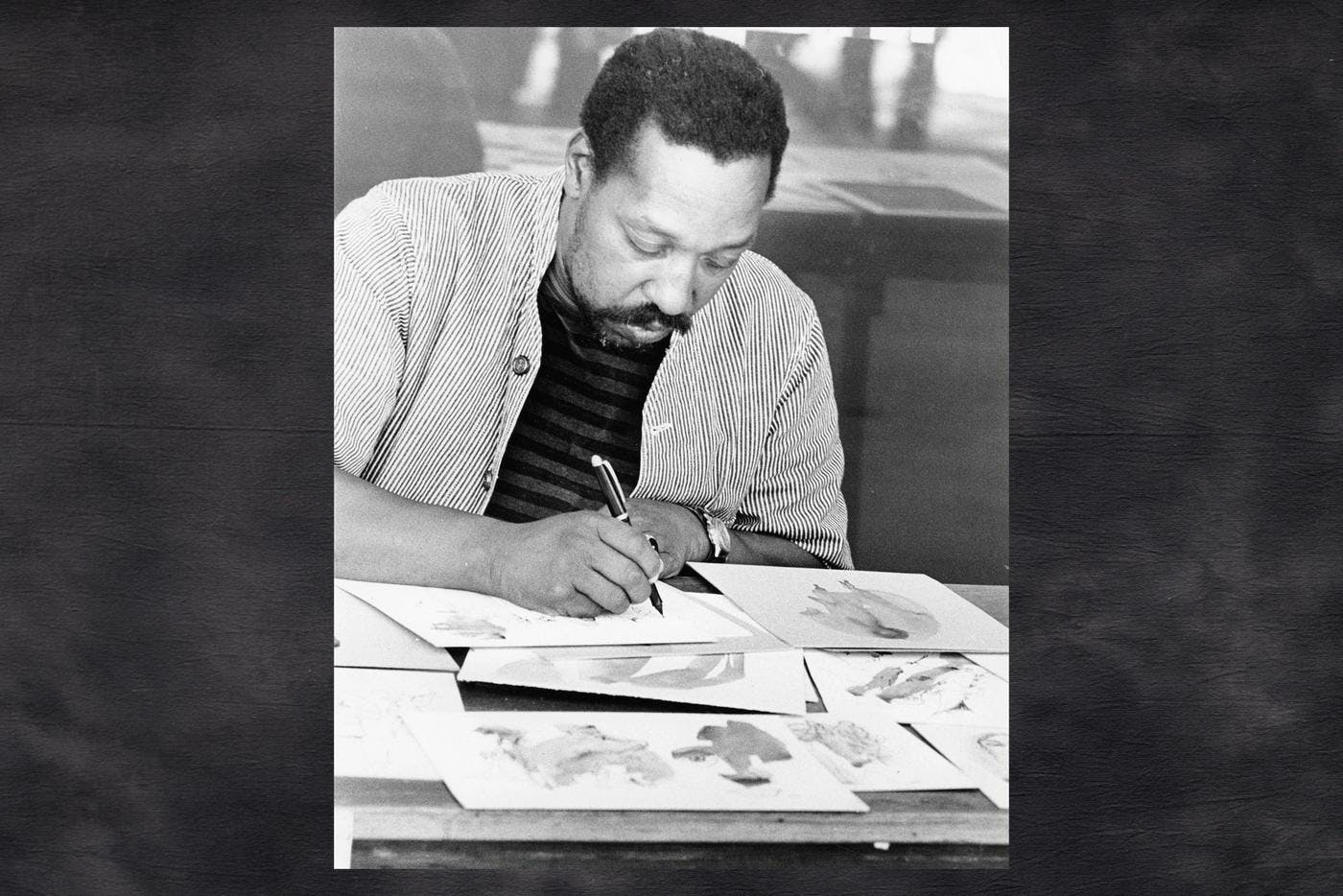

The first Black art instructor in Washington was an experimental artist ahead of his time.

For three decades, this Seattle DJ electrified the airwaves, paving the way for future Black radio personalities.

A poet at heart, this soul singer/songwriter is inspiring the next generation of Seattle musicians.

As a founder of Digable Planets and Shabazz Palaces, the Seattle rapper has pushed hip-hop to the outer limits.

The Seattle rapper keeps his memories of the Central District alive with vivid lyrics and a jazz sensibility.

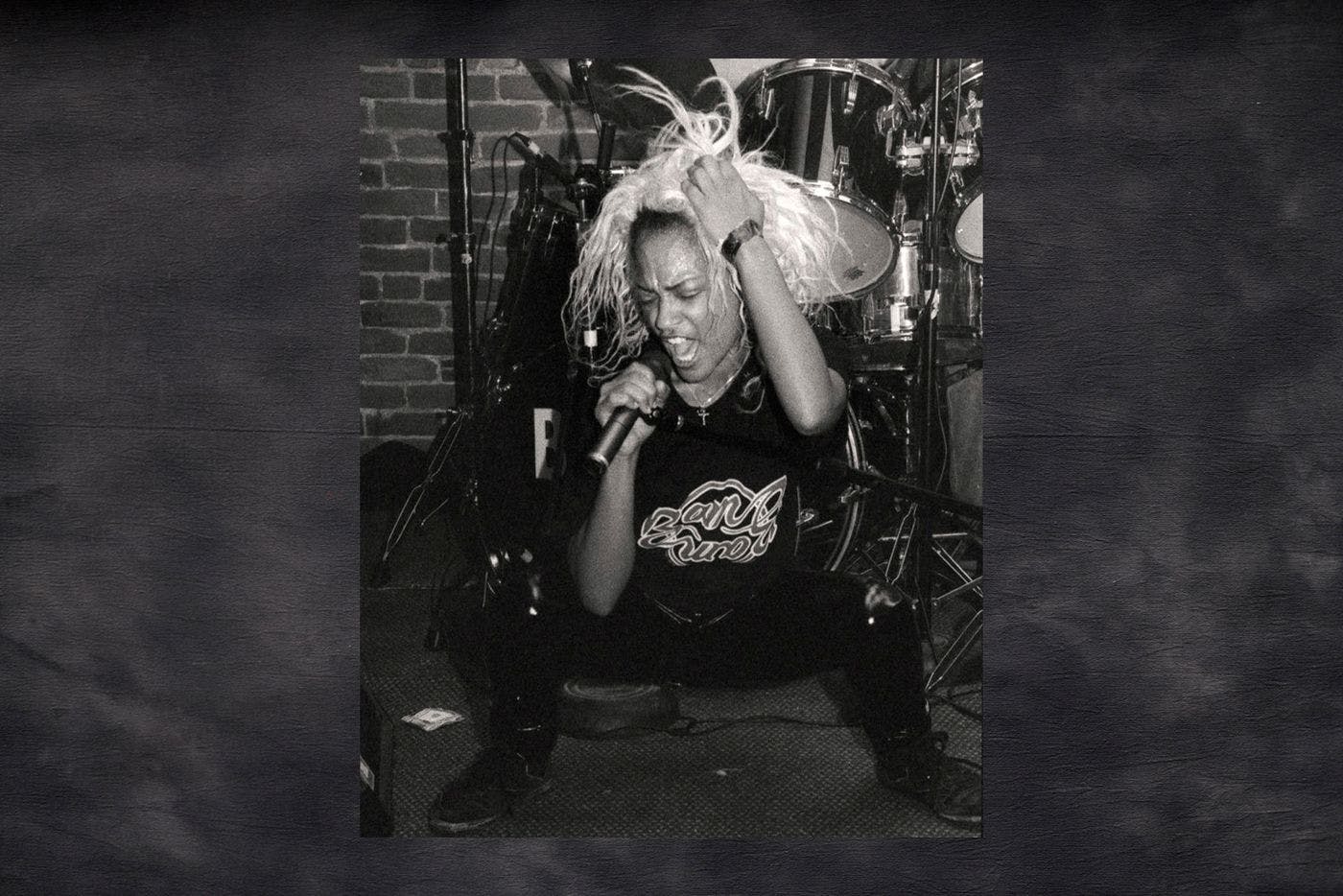

A pivotal figure in Seattle’s proto-grunge scene, the Bam Bam singer has been long-overlooked. Now, rock history is being rewritten.

Meet a Seattle music pioneer and the band carrying the legacy of Northwest rock forward.

This beloved Seattle DJ found his divine calling in music — and in sharing it with others.

Composing meditative music with a looping pedal, this Seattle cellist has charted her own sonic path.

Thanks to our Sponsors

Your support helps Crosscut create projects like Black Arts Legacies. Learn how you can help with a one-time donation or recurring membership.

Support Crosscut