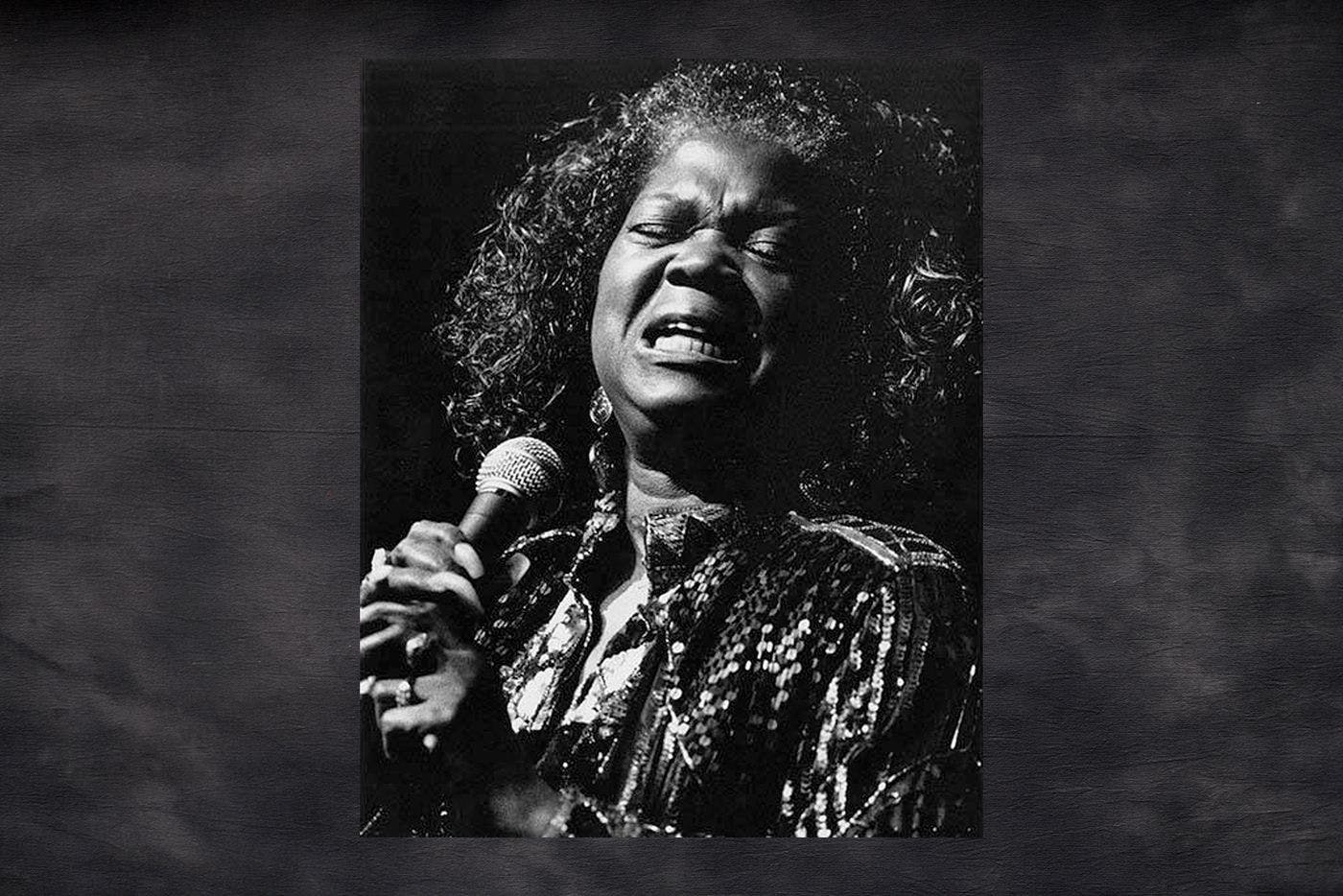

Ernestine Anderson

With a voice like ‘honey at dusk,’ the singer helped put Seattle’s early jazz and blues scene on the map.

A fount of knowledge for the jazz community, the trombonist and living legend is shaping the next generation of Seattle musicians.

by Jas Keimig / June 19, 2023

Amid the acrid smell of coffee and the creak of folding chairs, a small but devoted crowd has gathered in the basement of the Langston Hughes Performing Arts Institute for the March 2023 installment of “Julian Speaks.” Every other month this year, 87-year-old trombonist Julian Priester guides a listening session through his extensive and influential musical catalog.

Today the complicated rhythms of Herbie Hancock’s “Hidden Shadows,” from the experimental 1973 album Sextant, emanate from the speakers.

“One, two, three, four, onetwothree, fourone, two three, fouronetwothreefour,” Priester says, counting out the beat of the funky, far-out song. The audience tries to nod along with him. He may have recorded “Hidden Shadows” 50 years ago, but Priester remains sharp as ever.

“You must have rehearsed it a lot before you played it in public,” says trumpeter Thomas Marriott, a founder of Seattle Jazz Fellowship, the organization behind these events.

The trombonist gives him a sly smile, then shakes his head.

“No,” he laughs. The response of a legend.

Priester’s career has followed the path of American jazz history from the mid-20th century to the present. Throughout his six decades in the music business, the Seattle-based trombonist has worked with the pantheon of music innovators of the past hundred years: Sun Ra, Muddy Waters, Duke Ellington, John Coltrane, Bo Diddley, Abbey Lincoln, Buddy Rich, Herbie Hancock and Dinah Washington, to name just a few.

Since the late 1970s, Priester has been connecting generations of Seattle jazz musicians to that lineage, primarily through his role as a Cornish College of Arts professor from 1979 until his retirement in 2011.

But Priester resists being labeled a local. “It diminishes my hold, ‘local’ — there's no excitement there. Somebody comes to Seattle from New York and then everybody gets excited,” he says. “I love living here, but I don't like being three hours behind.”

Nevertheless, he’s left an indelible mark on the city as both a player and a teacher.

“If you’re playing and you look out in the audience and Julian is sitting there — a man who’s been on the stage and was friends and roommates and bandmates with all of your heroes — you’re not gonna be bullshitting,” Marriott says of Priester’s stature.

The two met playing jam sessions when Marriott was a teen and have grown close in recent years. “It’s important for people like Julian to be out in public, playing or not, because it keeps everybody honest.”

Priester was born in Chicago in 1935, the youngest of six children. Growing up in the segregated city, he got introduced to jazz as a child by his older brother James, who’d play jazz records with his friends. “The names of the players were like science fiction,” Priester recalls. “Bird, Miles, Duke, Hawk.”

He quickly developed an ear for music and could recreate on piano the tunes from his brother’s records. At DuSable High School, Priester studied under distinguished instructor Capt. Walter Henri Dyett and picked up the trombone after more popular classes like piano and trumpet had waiting lists. It was love at first slide.

In the early 1950s, the young trombonist joined Sun Ra’s Arkestra after being connected to the influential bandleader through a friend, saxophonist Charles Davis. “[Playing the Arkestra] was a wonderful experience that helped me grow and expand my knowledge and my ability to play my instrument,” Priester says. “Because in Chicago, if you weren’t ready, you’d be embarrassed.”

Over the next two decades, Priester bounded around the country working with some of jazz’s top brass. He toured with Lionel Hampton in 1956 (“He had a habit of hiring young people so he didn’t have to pay them like he had to pay older musicians," Priester notes, "but for me that was heaven”), then with Dinah Washington in 1958 (“There’s no comparison — she was really passionate,” he says).

In 1959 he settled down in New York with Max Roach’s crew, eventually releasing his first records as bandleader — Keep Swingin’ and Spiritsville — before leaving Roach in the early ’60s to work as a sideman on projects like John Coltrane’s Africa/Brass and with musicians like Duke Ellington, Andrew Hubbard, Booker Little and Clifford Jordan.

“His trombone playing is part of the collective sound of what we think of when we think of jazz because he's been a part of so many important musical projects and groups since the ’50s,” Marriott says. “It’s difficult to come up with an original style, especially when you play an instrument that's been well-defined by others before you. And Julian is one of those people that has a unique and identifiable way of playing the trombone.”

Praised by Jazz Times as “astonishing in his ability to get around the horn at top speed and low volume,” Priester is also known as “a trombonist with an amiable, misty tone and an inquisitive instinct,” according to The New York Times, who “has been flouting the divide between jazz’s mainstream and the avant-garde since before that line was drawn.”

In 1970, Hancock drafted Priester for a sextet that would become known as the Mwandishi group after their eponymous first album together. To reflect a greater consciousness of their African heritage and bring them closer as a family, all the group’s members took on Swahili names, which is how Priester got the title Pepo Mtoto — “spirit child” — a name he’s still known by today.

The project combined elements of funk, electronic, and classical music. With its trilling horns, groovy bass lines, bombastic percussion and experimental time signatures, the improvisational record is a far-out, Afro-futuristic vision of what jazz could be.

“The Herbie Hancock experience, for me, is a memory that stays fresh in my mind after 53 years. It was like it was yesterday,” Priester says of that expansively creative period. “That's how much of a life-changing experience it was. I relive it daily.”

After the Mwandishi group disbanded in 1973, Priester landed in San Francisco and supported himself by teaching and playing. But in 1979 he was invited to join the music faculty at Cornish.

Seeking stability, the trombonist and his young family (Priester had recently married his wife Nashira, and they’d had their first child) packed up to Seattle and landed on south Beacon Hill. He’s lived here ever since, now in the Central District.

When he arrived, Priester’s knowledge of the local jazz scene began and ended with the Seattle jazz greats he’d known and played with, including Ray Charles, Quincy Jones and Ernestine Anderson.

If you learn how to listen — and it does take some doing — you’ll get more out of the experience.”

But after settling in, he got to work collaborating with other local talents like vocalist Jay Clayton, percussionist Jerry Granelli, pianist Stanley Cowell, bassist Gary Peacock and pianist Wayne Horvitz, as well as releasing his own recordings. He even popped up on Seattle drone band Sunn O)))’s song “Alice” (from 2009), in honor of Alice Coltrane.

While Priester continued to perform on a national stage with musicians like Dave Holland, Charlie Haden and Sun Ra, Seattle provided him space to grow his art form.

“Without Cornish I’d probably be in L.A. doing studio work with no artistic expression whatsoever,” he told the Seattle P.I. in 1981. “My heart lies in performing and writing. I can concentrate on those things here. I guess I should say Seattle has been great for me.”

As an instructor, Priester incorporated all the wisdom passed down to him by his stellar mentors and collaborators like Sun Ra and Hancock.

“I made [my students] aware of sound. I told them to listen. There’s music all over. You listen, concentrate, and play what you hear,” he says. “When you learn by the book, the output is not fresh, it’s not creative on a higher level. If you learn how to listen — and it does take some doing — you’ll get more out of the experience.”

Steve Moore, who met Priester as a 15-year-old trombonist and has looked to him as a mentor for 30 years, says Priester is totally focused on musical excellence.

“There’s the nuts and bolts of playing your instrument, and we did talk about that stuff. But Julian has a pretty advanced perspective on the philosophy and mental aspect of music,” Moore says. “That sort of approach to improvisation and musicality as a way of life — he imparted that [philosophy] in his work as a teacher at Cornish and as a musician on the stage.”

“He's very gracious, patient and gentle,” adds pianist Dawn Clement, one of Priester’s Cornish students and a member of his band Priester’s Cue. “I think he draws out of you something that is super-authentic and in the moment. I am who I am because of him.”

Since the pandemic hit, Priester has reduced his public performances, but still picks up his trombone to play at home. He hails from a generation of jazz giants, and in his decades of teaching he’s planted the seeds of that knowledge in his students and mentees.

“I would love to pass on the true history of this art form we call jazz. I just want to reveal the importance of sound in our lives because we walk around hearing but we don’t listen,” Priester says. “No one really knows what jazz is. It’s a connection to the soul. It’s healing.”

Black Arts Legacies Writer

With a voice like ‘honey at dusk,’ the singer helped put Seattle’s early jazz and blues scene on the map.

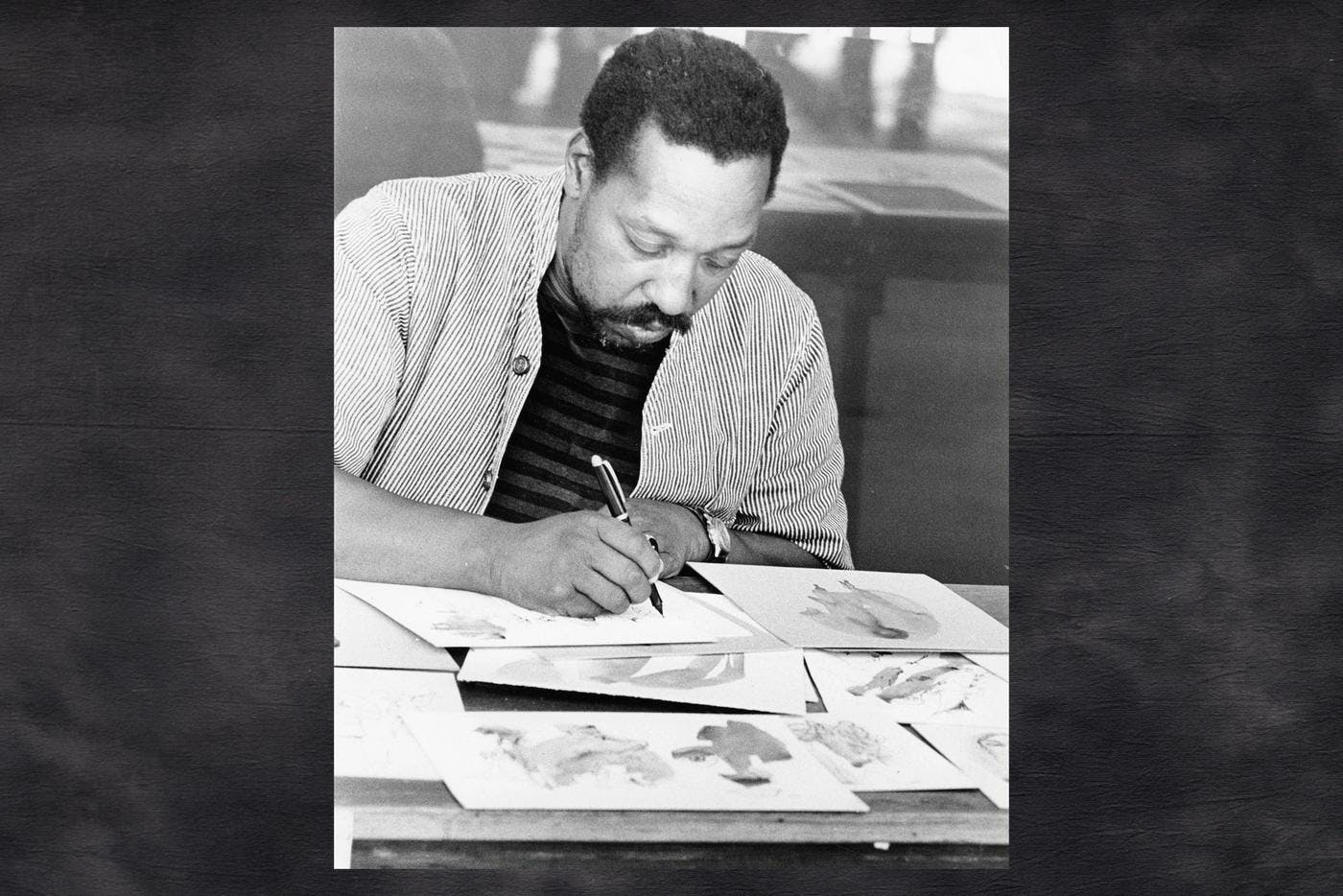

The first Black art instructor in Washington was an experimental artist ahead of his time.

For three decades, this Seattle DJ electrified the airwaves, paving the way for future Black radio personalities.

A poet at heart, this soul singer/songwriter is inspiring the next generation of Seattle musicians.

As a founder of Digable Planets and Shabazz Palaces, the Seattle rapper has pushed hip-hop to the outer limits.

The Seattle rapper keeps his memories of the Central District alive with vivid lyrics and a jazz sensibility.

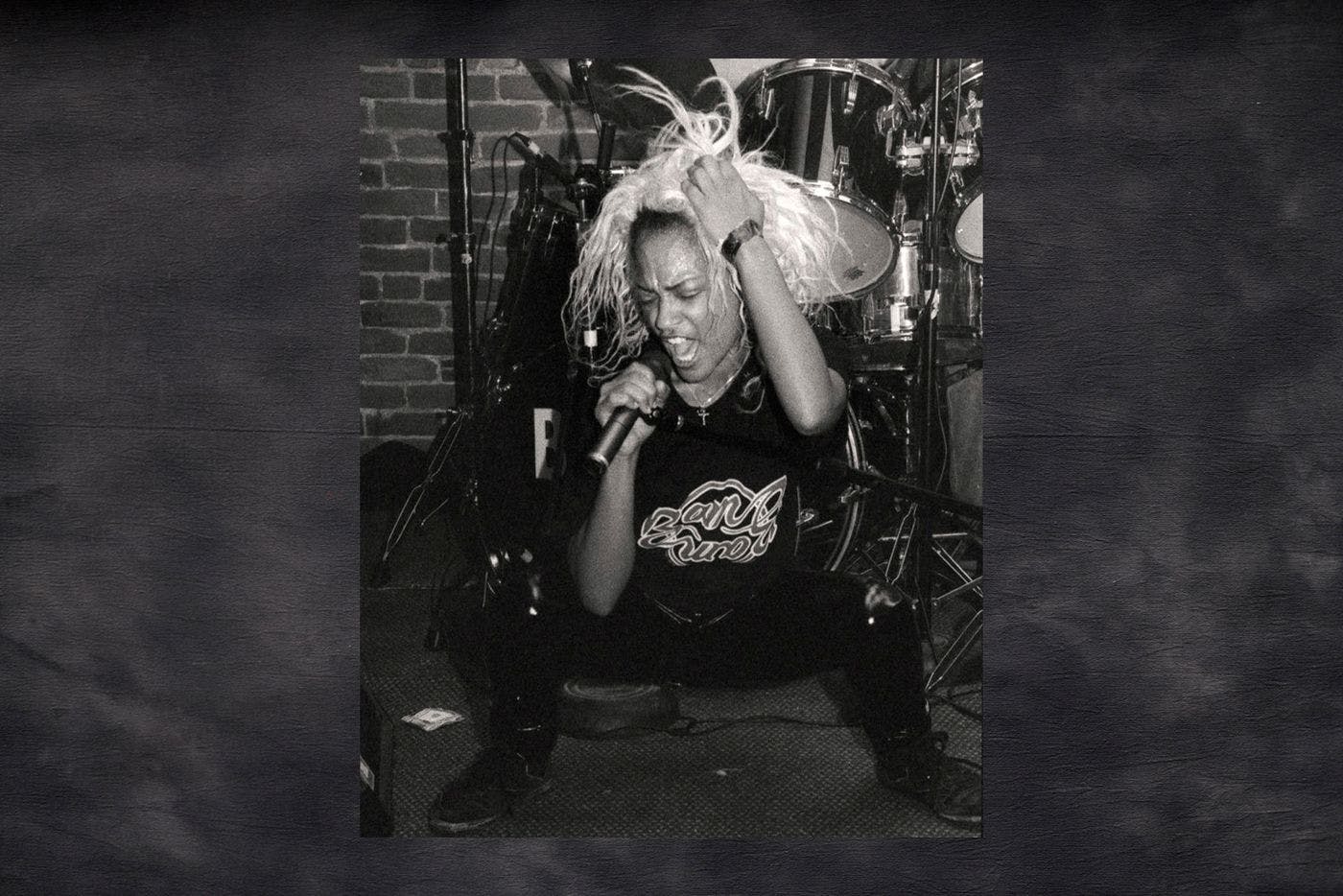

A pivotal figure in Seattle’s proto-grunge scene, the Bam Bam singer has been long-overlooked. Now, rock history is being rewritten.

The talented multi-instrumentalist uses music to string communities together.

Meet a Seattle music pioneer and the band carrying the legacy of Northwest rock forward.

This beloved Seattle DJ found his divine calling in music — and in sharing it with others.

Composing meditative music with a looping pedal, this Seattle cellist has charted her own sonic path.

Thanks to our Sponsors

Your support helps Crosscut create projects like Black Arts Legacies. Learn how you can help with a one-time donation or recurring membership.

Support Crosscut