Julian Priester

A fount of knowledge for the jazz community, the trombonist and living legend is shaping the next generation of Seattle musicians.

As a founder of Digable Planets and Shabazz Palaces, the Seattle rapper has pushed the limits of what hip-hop says and sounds like.

by Kemi Adeyemi / June 1, 2022

“I can’t explain it with words / I have to do it” may be Ishmael Butler’s personal mantra. It’s a bit ironic, given that he has made a career as a rapper, painting vivid pictures with words. The lyric comes from a song he released with the avant-garde Seattle hip-hop group Shabazz Palaces in 2011, nearly 20 years after he won a Grammy with the jazz-inflected, alternative hip-hop group Digable Planets. Butler has spent decades making music that pushes the limits of what hip-hop says and sounds like — but words can only do so much. Throughout his career he has created lush sonic environments meant to make us feel something, too.

Part of the long history of creative visionaries raised in Seattle’s Central District, Butler says his grandparents left the South for the same reasons as many Black people: “for exploration and work opportunities at Boeing.” The family left Louisiana for Bremerton before taking root in Yesler Terrace, Washington state’s first public housing complex — also the first racially integrated development in the U.S. They eventually bought a house in the historic Central District, where Butler was born in 1969.

At Garfield High School, Butler was a standout basketball player, who as a senior took the team to the state championships in 1987. He went on to play Division I basketball at the University of Massachusetts Amherst. He was always musical, though. “I learned saxophone jazz and classical from Wadie Ervin at Meany Middle School,” he says, noting the teacher who influenced generations of local musicians. “I got into production [by] going over to my friend Marcel Sanders' house and using his drum machine.”

Eventually, the pull of music led him to drop out of college. He caught a major break when he auditioned for Pendulum Records as “Butterfly” in the group Digable Planets, alongside Craig “Doodlebug” Irving and Mary Ann “Ladybug Mecca” Vieira. Their music was a bright spot in the jazz-inflected alternative rap music that was coming out of New York in the early 1990s. Their song “Rebirth of Slick (Cool Like Dat),” with its pluck of descending bass notes, harmonic horn line and punchy yet laid-back rapping, would score a 1994 Grammy.

Their next two albums didn’t quite capture that early success, however, and creative differences led the group to disband in 1996. Butler seemed to quietly disappear from the music scene, living what he describes as a “hermit life” in New York before returning to Seattle. But he didn’t entirely stop making music — he recorded solo albums that were never released; his 2003 debut as Cherrywine (with Seattle guitarist Thaddeus Turner and bassist Gerald Turner, as well as producer Bubba Jones) explored some neo-psychedelic sounds, but didn’t really make waves.

He continued to work creatively but, as he says in a 2014 interview with Complex, “My mom passed away and I was basically disoriented, disenchanted. I felt depressed. I didn’t really have any musical aspirations. I was mourning.” With the encouragement of friend and percussionist Tendai Maraire (whose father, Dumisani Maraire, is credited with bringing Shona music from Zimbabwe to the Pacific Northwest and across the U.S.), Butler launched into his third act.

Teaming up as Shabazz Palaces, Butler and Maraire have pushed hip-hop into new frontiers. Across two EPs and five albums, the group has perfected an off-kilter aesthetic: standard 4/4 beats are rare, and there are few, if any, A-B-A-B song structures — and even fewer catchy, radio-friendly hooks. Instead, the band experiments with creating balance out of contrasting textures: The warmth of live instruments — guitars, mbira, drums — plays against sharp and clattering digital beats, which are rounded out by cosmic loops and keyboards that are dragged through goopy filters.

These cacophonous sounds are smoothed out by Butler’s even musical delivery. His lyrics are a savvy blend of abstract imagery (“Forever that's the theme, it's never what it seems/Below the diamond showers above the purple clouds”) and plainspokenness (“Well I never was the type to live a sedentary life/I always had to get up and out,” both from 2020’s “Ad Ventures.”)

The paradoxical clarity of Shabazz Palaces’ dissonance shook up the Seattle music scene in 2009. The launch of the first EPs was shrouded in mystery. The CDs were packaged in cardboard sleeves featuring intricately embroidered patches. There were no liner notes or images of the artist(s) anywhere. In a 2022 podcast series devoted in part to his work, Butler says of this time, “It was never really about secrecy as much as it was about letting your music speak for you. … I wanted to lead with the music.”

It worked. Shabazz Palaces secured a deal with Sub Pop Records, and the full-length debut, Black Up, was released in 2011 to critical acclaim. Running at 36 minutes, the compositions are lit up with astral glitters and shimmers, as if “going deep into space,” says Seattle DJ Larry Mizell. He describes the sound as “getting bigger, weirder, deeper, harder.” Music critic Sasha Frere-Jones aptly describes the overall vibe as “high-resolution disorientation.”

The sonic and lyrical density of Shabazz Palaces may be at times disorienting, but its music injects moments of rest that allow the body to breathe and the mind to wander. Over the spare beat of the song “Recollections of the wraith,” Butler works to “clear some space out so we can space out.” That lyric, from Black Up, also speaks to Butler’s approach to music.

“Over the years I have shifted from very deliberate, mapped-out compositions to a freer, more instinctive method of capturing spontaneity,” he says, preferring this to “pursuing a predetermined result.”

For Butler, spacing out is an opportunity to clear his mind and be available to his instincts — which have always led him to make genre-bending music that never caved to the demands of the commercial music industry. It is perhaps no surprise that he has surrounded himself with other creative visionaries.

He is a founding member of the Black Constellation, a collective of Seattle musicians, visual artists, filmmakers and designers, which was recently chronicled in the KEXP podcast Fresh Off the Spaceship. The collective, which came together in the 2000s, has led to multiple music collaborations — Stas Thee Boss is featured on Shabazz Palaces albums, and Erik Blood mixed and engineered Lese Majesty (2014) — as well as exhibitions and live programming at art museums. In 2021, Butler was a resident artist in his own right at the Henry Art Gallery.

For someone who has long talked about the music industry as a young person’s game, Butler, now in his 50s, shows no signs of leaving it. His knack for drawing out multidimensional creative visions primed him for his current role as A&R (artists and recording) representative at Sub Pop, where he was instrumental in signing Seattle rapper Porter Ray. His skills as a tastemaker come from a rich life in the music industry, where he has experienced everything from the tedium of interning at a label, to the highs of receiving a Grammy, to musical dry spells.

The Northwest will continue to play an important role in his musical innovations — whether in Shabazz Palaces, in the artists he brings into Sub Pop or in the creative collaborations he dreams up along the way. “The rainy gray season in Seattle,” he says, “is a good time to shed, study, practice and learn new things while staying indoors.”

Black Arts Legacies Project Editor

A fount of knowledge for the jazz community, the trombonist and living legend is shaping the next generation of Seattle musicians.

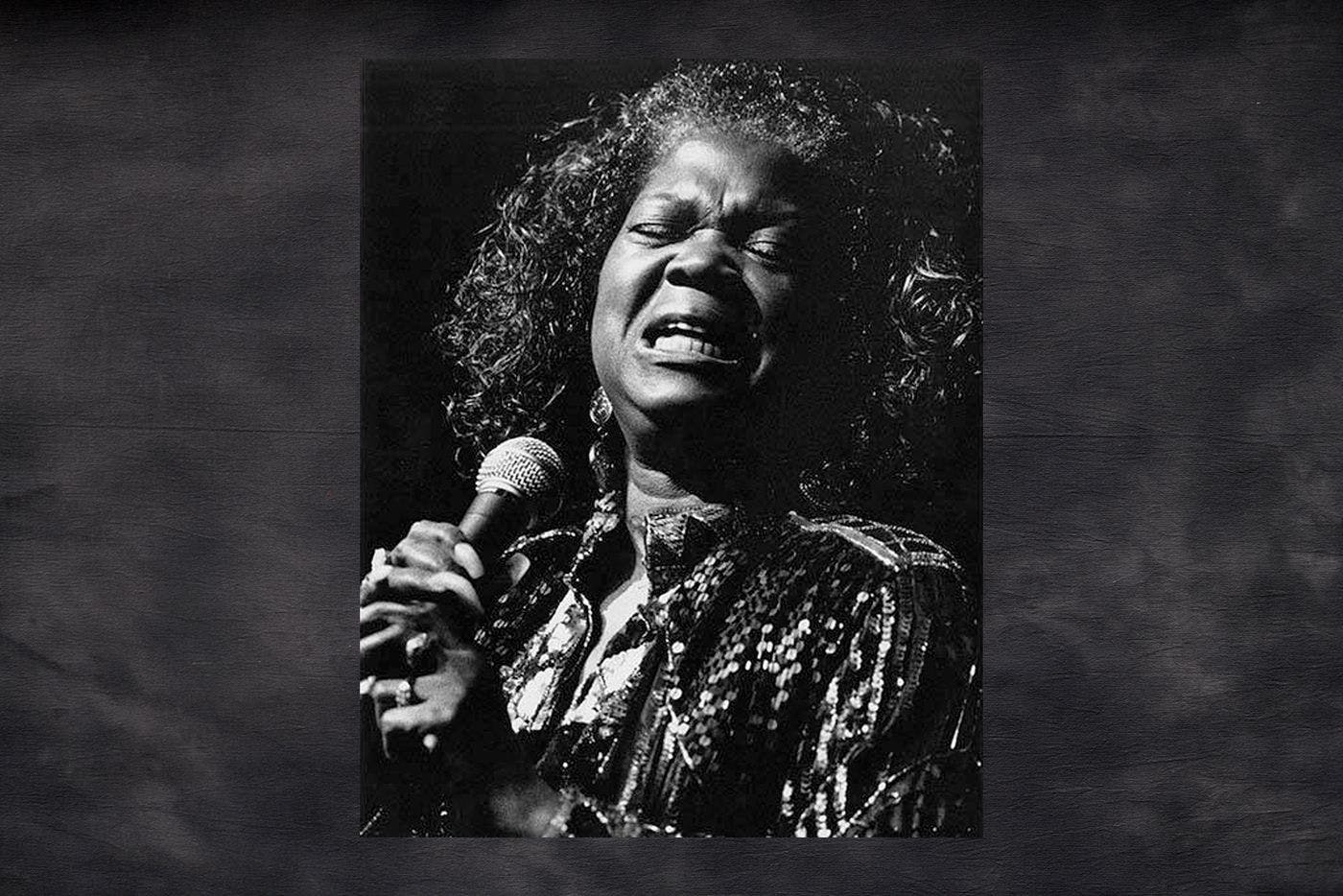

With a voice like ‘honey at dusk,’ the singer helped put Seattle’s early jazz and blues scene on the map.

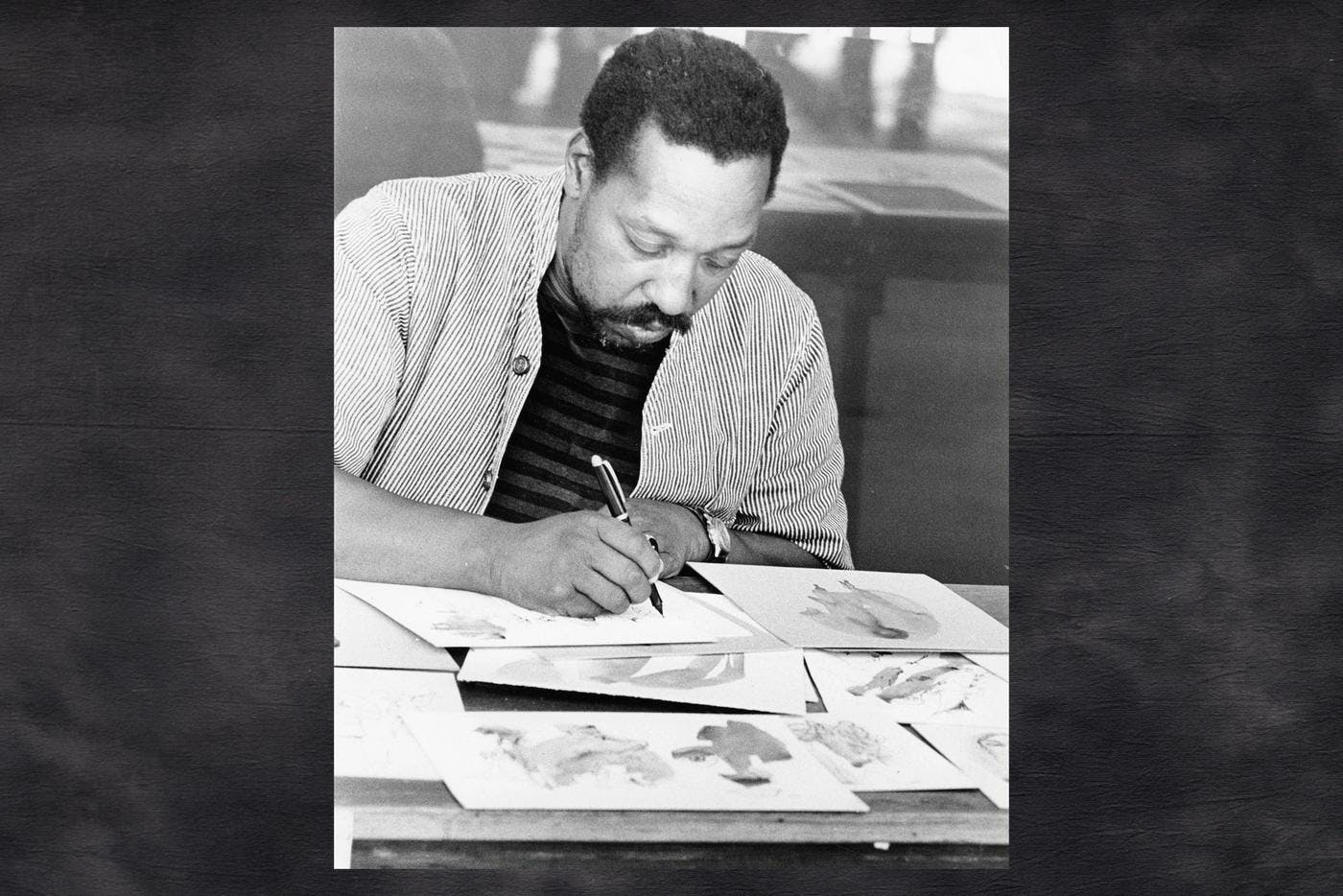

The first Black art instructor in Washington was an experimental artist ahead of his time.

For three decades, this Seattle DJ electrified the airwaves, paving the way for future Black radio personalities.

A poet at heart, this soul singer/songwriter is inspiring the next generation of Seattle musicians.

The Seattle rapper keeps his memories of the Central District alive with vivid lyrics and a jazz sensibility.

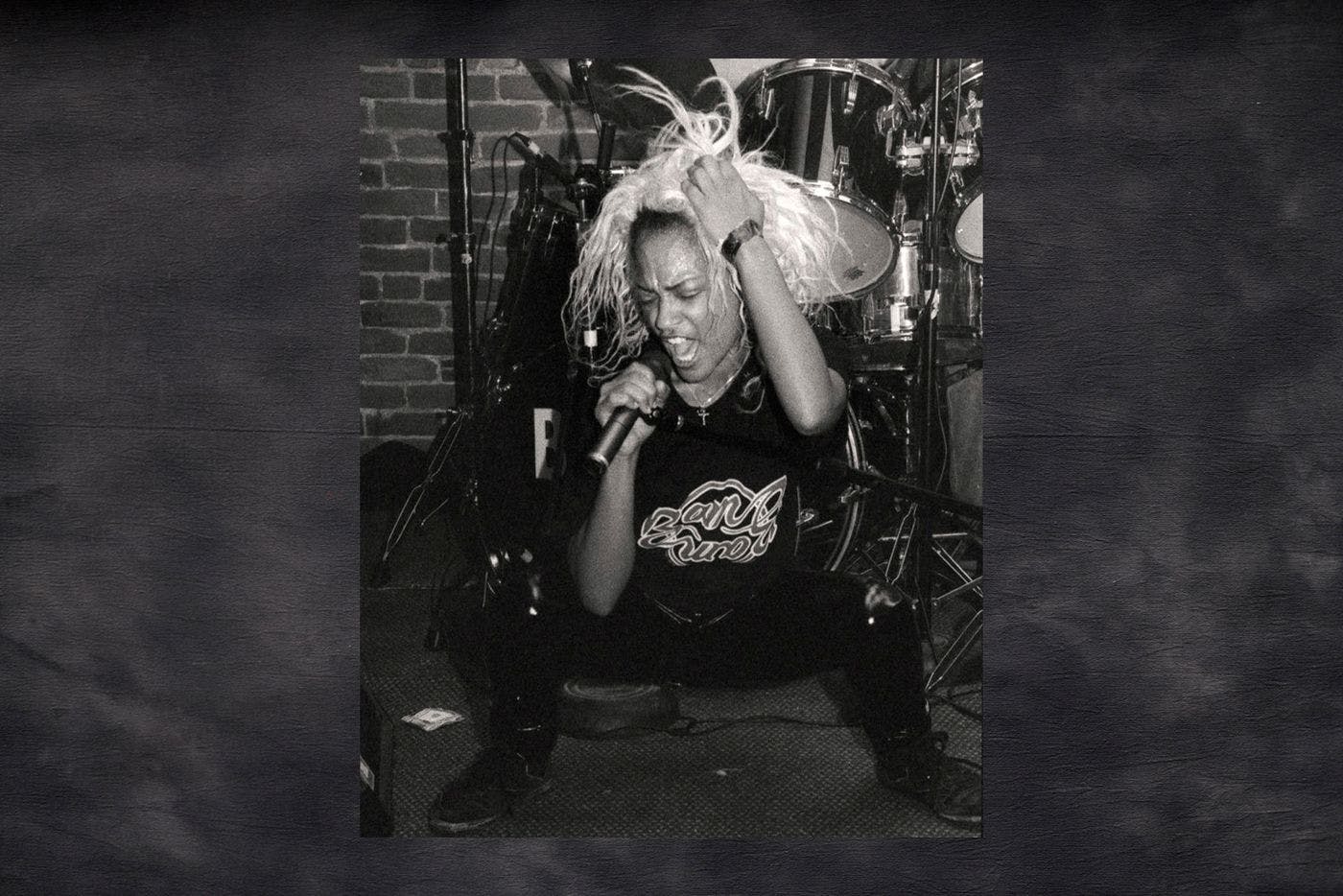

A pivotal figure in Seattle’s proto-grunge scene, the Bam Bam singer has been long-overlooked. Now, rock history is being rewritten.

The talented multi-instrumentalist uses music to string communities together.

Meet a Seattle music pioneer and the band carrying the legacy of Northwest rock forward.

This beloved Seattle DJ found his divine calling in music — and in sharing it with others.

Composing meditative music with a looping pedal, this Seattle cellist has charted her own sonic path.

Thanks to our Sponsors

Your support helps Crosscut create projects like Black Arts Legacies. Learn how you can help with a one-time donation or recurring membership.

Support Crosscut