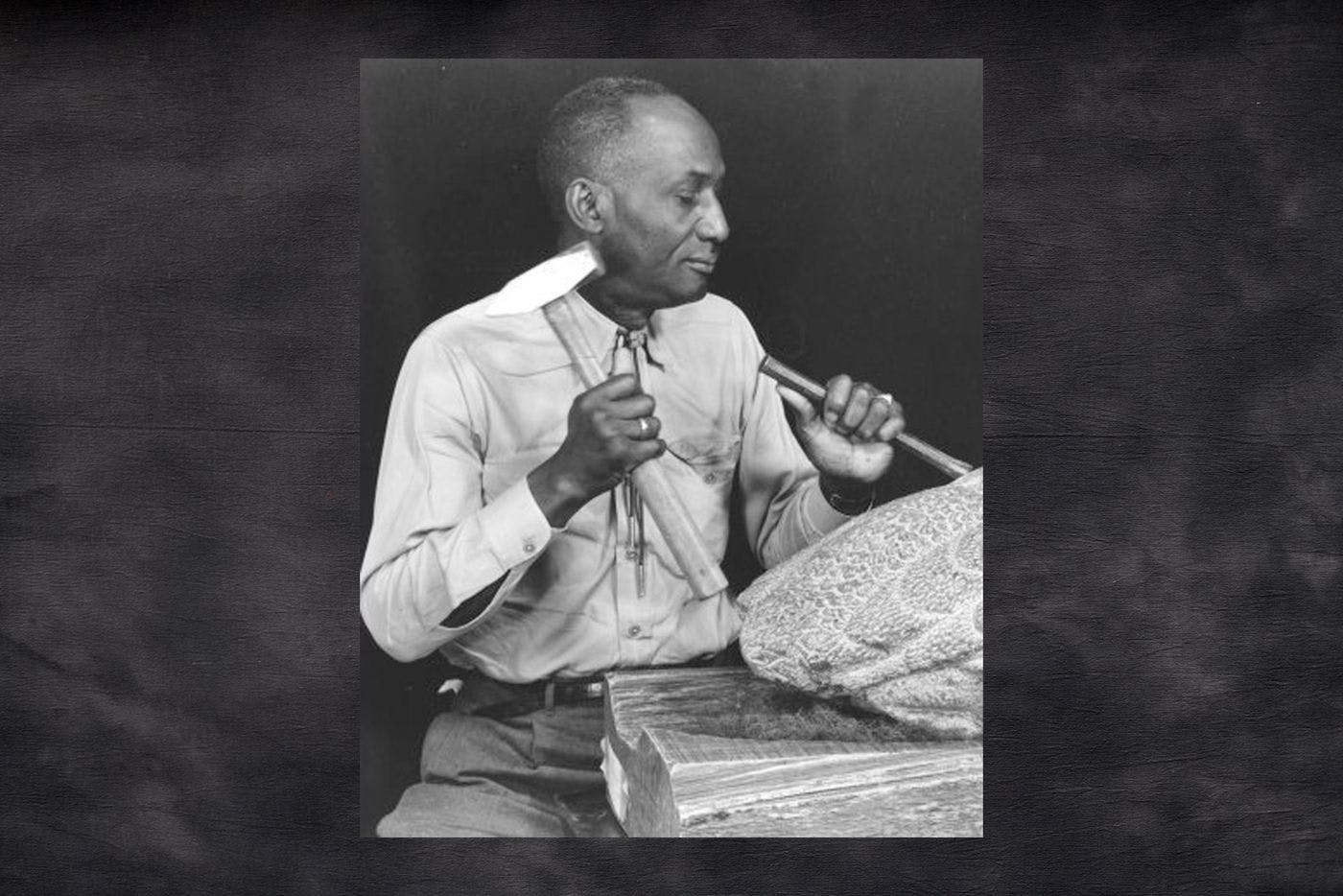

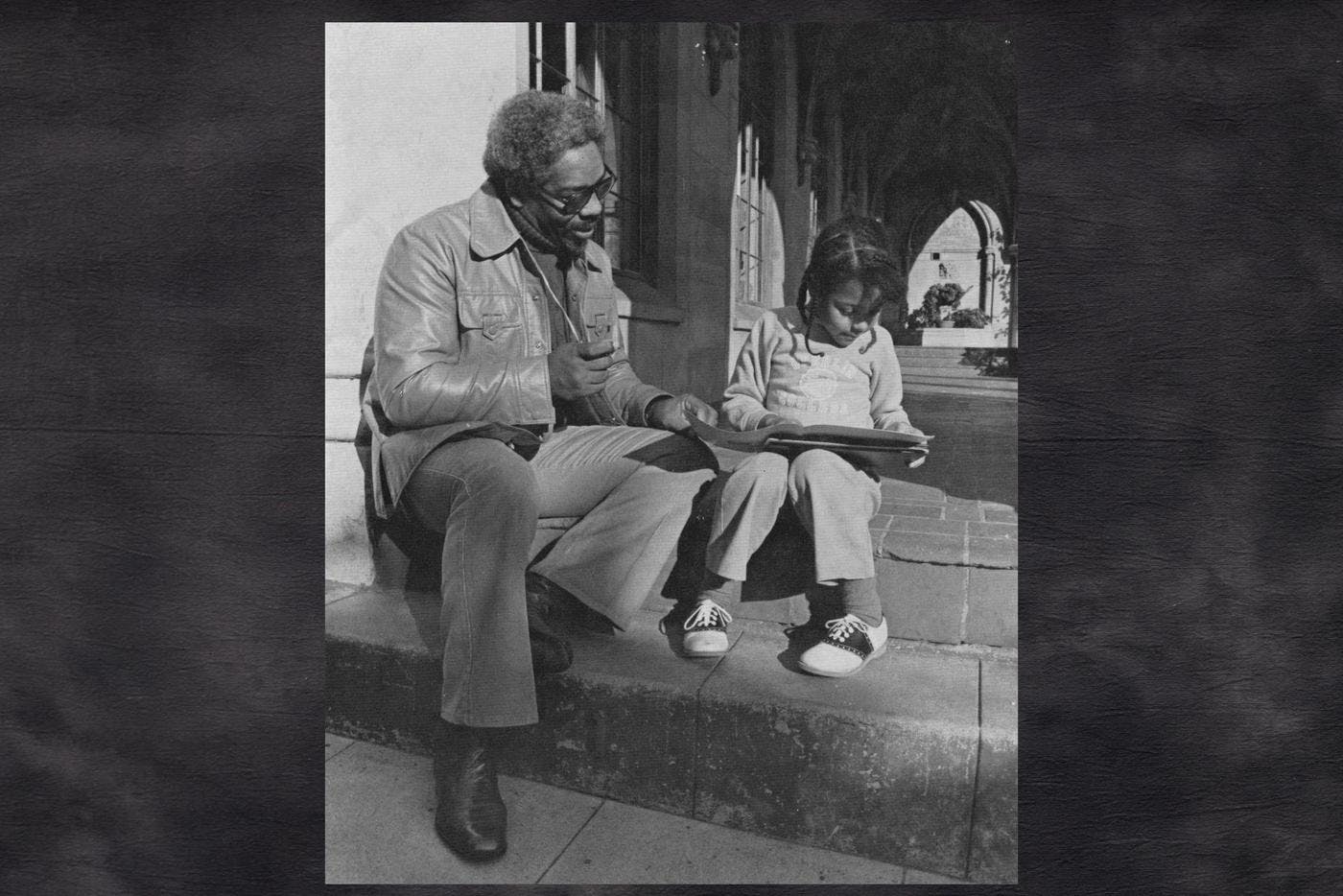

James W. Washington Jr.

An influential member of the noted Northwest School, the Central District sculptor turned his home into a community center for artists.

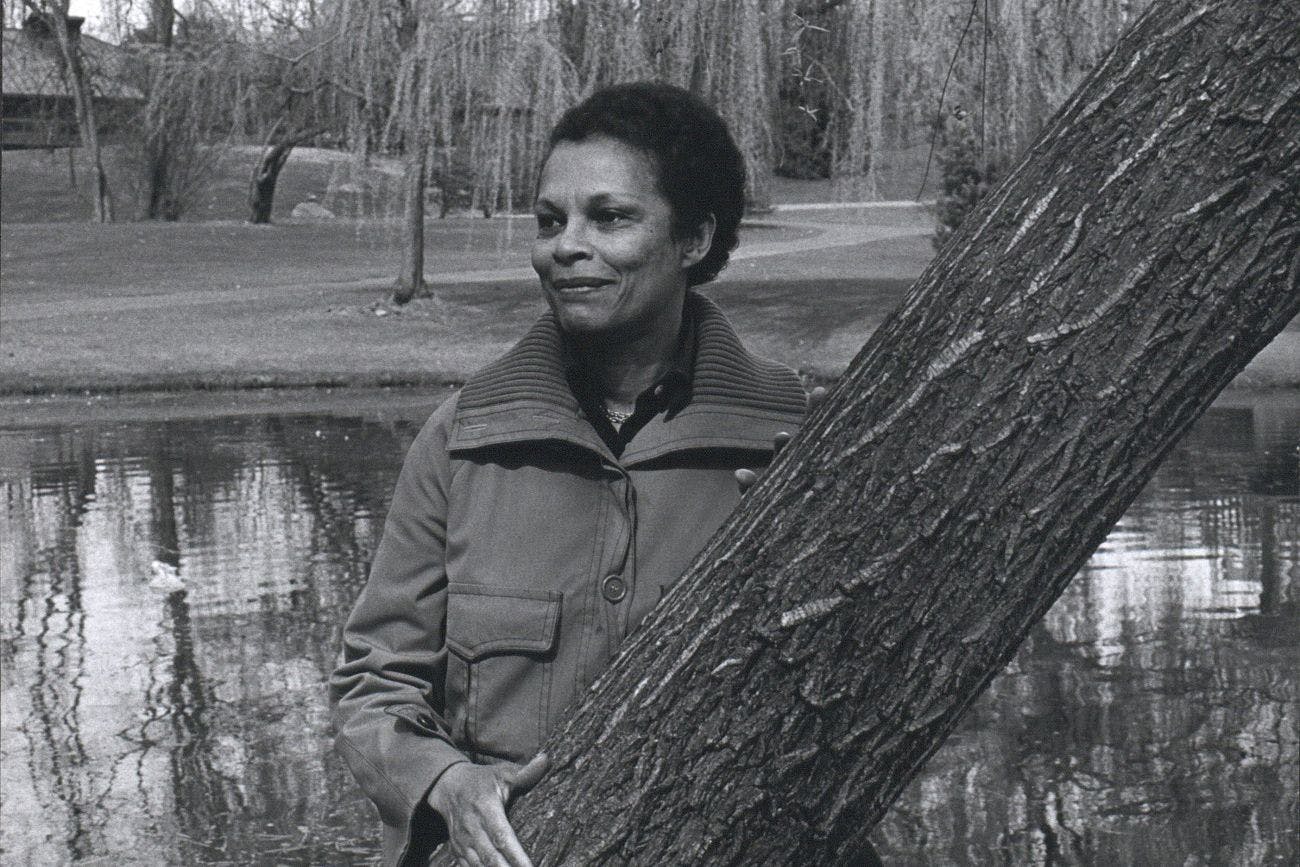

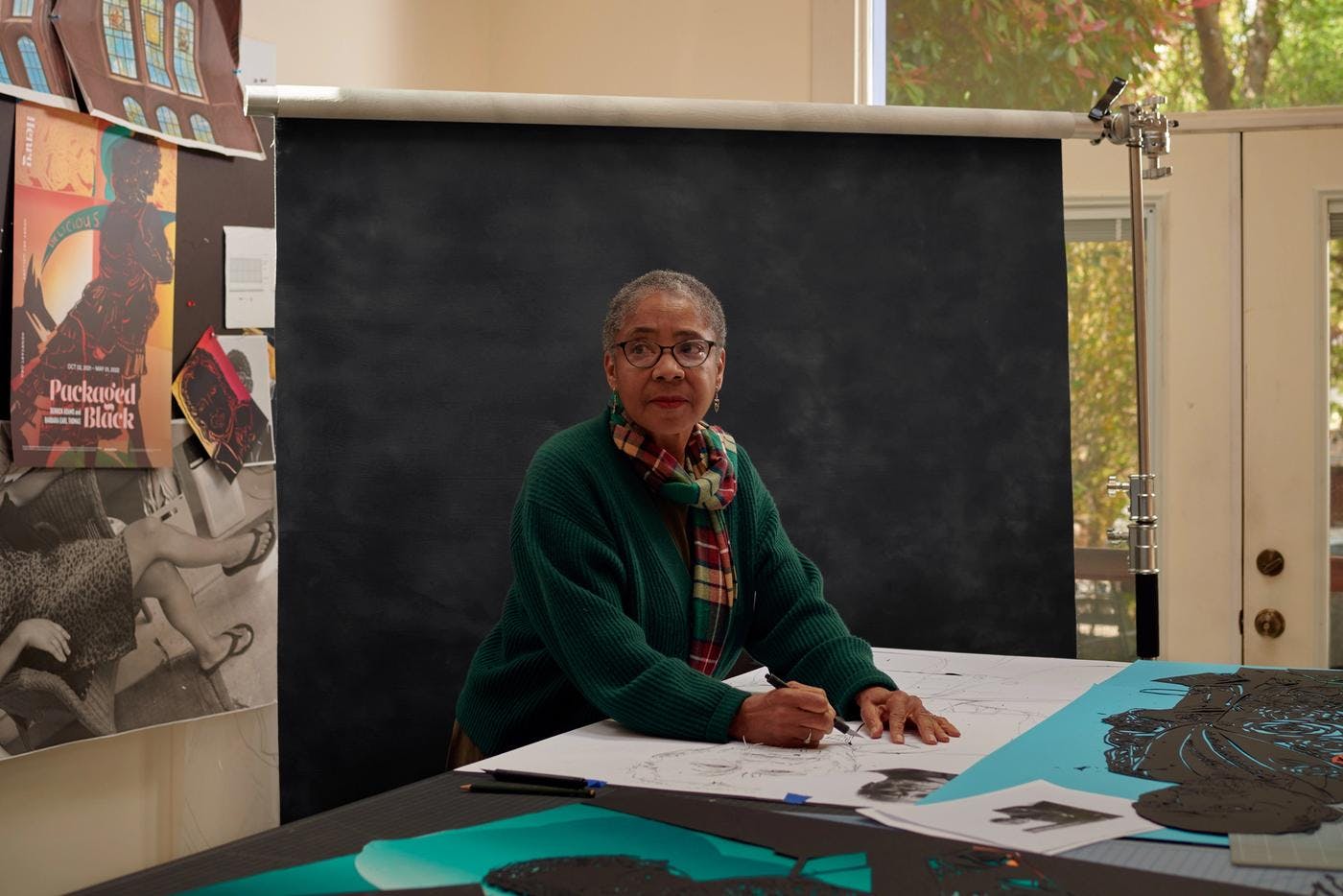

A pioneer of glass techniques, this renowned creator is one of the few Black female artists in her medium.

by Jas Keimig / June 14, 2024

On a recent spring morning in an open-air hot shop behind an old wood house in Seattle’s Chinatown-International District, a furnace glowed red in contrast to the gray day.

Glass artist Debora Moore sat in front of the flames, dressed in jeans, a black T-shirt and black shades. She attended to the cooling glass at the end of her rod, shaping the substance into petals, leaves and disc florets: a sunflower. Moore is known for such delicate, lifelike botanicals and her wild, skillful facility with color and pattern. Crafting this sunflower is basically muscle memory for her.

“My husband gave me the shop to do whatever I wanted and experiment,” says Moore, referring to her late husband, Benjamin Moore, a giant in the American studio glass movement who passed in 2021. He bought the old wood house in front of the hot shop back in 1985. (From the mid-1940s to the late ’60s the building had simultaneously served as a Baptist church and a brothel.) The facade still bears his name, and Moore continues to use it as her studio.

“I didn’t want to make what everybody else makes,” Moore says of her flora. “I make what I want to make and how I see it. There’s no books or anything to tell you how to make glass flowers; everybody makes them in their own different way, and I just came up with my own way.”

Since the late 1980s, Moore has established herself as one of the best botanical glass artists in the world, with a resume that stretches from Seattle to Italy. She worked in Dale Chihuly’s studio as an assistant and colorist; cut her teeth as a glassblower at Ballard’s Glass Eye Studio (the largest privately owned hot shop in the U.S.) and taught at the vaunted Pilchuck Glass School in Stanwood. In 2005, she became the first woman and first Black artist-in-residence at the legendary Abate Zanetti School of Glass on the island of Murano in Venice.

“The community has become more diverse since I started blowing glass 30 years ago,” Moore says. “First of all, there were no women, and no Black women at all. … As an African American woman being gaffer,” she recalls, “some men [didn’t] want to take instructions from me, and that happened to me quite a bit.” Moore proved herself with her artwork and persistence, becoming a respected figure in the international glass scene.

Eschewing the cool, smooth nature of glass, Moore manipulates the molten substance to create shapes and textures that resemble organic matter — moss, tree bark, frost, the soft flesh of flower petals. She has built flowering, free-standing wisteria, magnolia, cherry and winter plum trees covered in powdery lichen and ripe blossoms, rendering them in exquisite detail over weeks of finely attuned glass-blowing processes.

Despite how lifelike her creations appear, fidelity to nature isn’t Moore’s goal.

“My whole thing is to capture the essence of whatever I’m studying that I wanna make,” she says. “It doesn’t have to be true to life, it doesn’t have to be a scientific embodiment. It’s just my vision and how I interpret what I’m seeing.”

Born on an Air Force base outside of St. Louis, Mo., in 1960, Moore spent most of her childhood and late teens shuttled from military base to military base, and served as an interpreter for her deaf mother. As a teenager, she moved with her family to Seattle, where she cared for her nieces and nephews while nursing a love of ceramics before taking her first glass class at the Pratt Fine Arts Center in the early ’80s. She immediately fell in love with the medium and applied her interest in nature to her craft.

“Glass is so malleable — it can move and do things and then you can just freeze it instantly. I found that glass was a perfect medium for what I was trying to say. It transmits and reflects light. It’s transparent, you can see through it. It’s viscous and malleable,” Moore reflects. “I thought it was a perfect medium for sculpting botanicals.”

Moore is a tinkerer. With 24/7 access to her hot shop, she spends hours perfecting and experimenting with new glass-blowing techniques. (How It’s Made is one of her favorite TV shows, and she’s often inspired by the manufacturing of things like golf clubs, steering wheels and chandeliers.) To create frost on her winter plum trees, she played around with crystal glass at different temperatures over different colors before finding the perfect combination to give it the right frostiness.

Orchids, one of the oldest flowering plants on the planet, fascinate Moore. “There are over 25,000 species of orchids, and I’ll never make all of the orchids that are out there,” she says. “Every time you study one orchid, there’s another to come.”

Much of her work renders them in astoundingly complex detail. For “Moth Orchid,” she manipulated the colors to react with one another, creating spider-like veins and imperfections like the ones found on real orchids. In “Blue Lady Slippers,” the bulbous orchid — Moore’s favorite — is a searing cobalt blue, its petals serenely drooping toward the ground. And in her “Red Moth Orchid” sculpture, the eponymous flower is a streaky white color with a burst of red in the middle, perched serenely on an equally patterned bit of bamboo.

Moore’s interest in orchids and other plant life has taken her around the world, from Jamaica to Antarctica, to understand how flowers, trees and moss all live together in the wild, growing and enmeshing with one another. Orchids, for instance, latch onto trees and bamboo so that they can have adequate access to sunlight and moisture. That organic interdependence is echoed in Moore’s relationship with glass art, fueling her experimentation and pushing the medium forward.

Moore is still sitting with the grief of losing her husband and another family member, but she’s slowly finishing a pre-pandemic project for the U.S. embassy in the Bahamas and planning future exhibitions. She remains an artist to her core.

“I have to make something,” Moore says. “It’s within me to create.”

Black Arts Legacies Season 3 is made possible in part thanks to support from 4Culture.

Black Arts Legacies Writer

An influential member of the noted Northwest School, the Central District sculptor turned his home into a community center for artists.

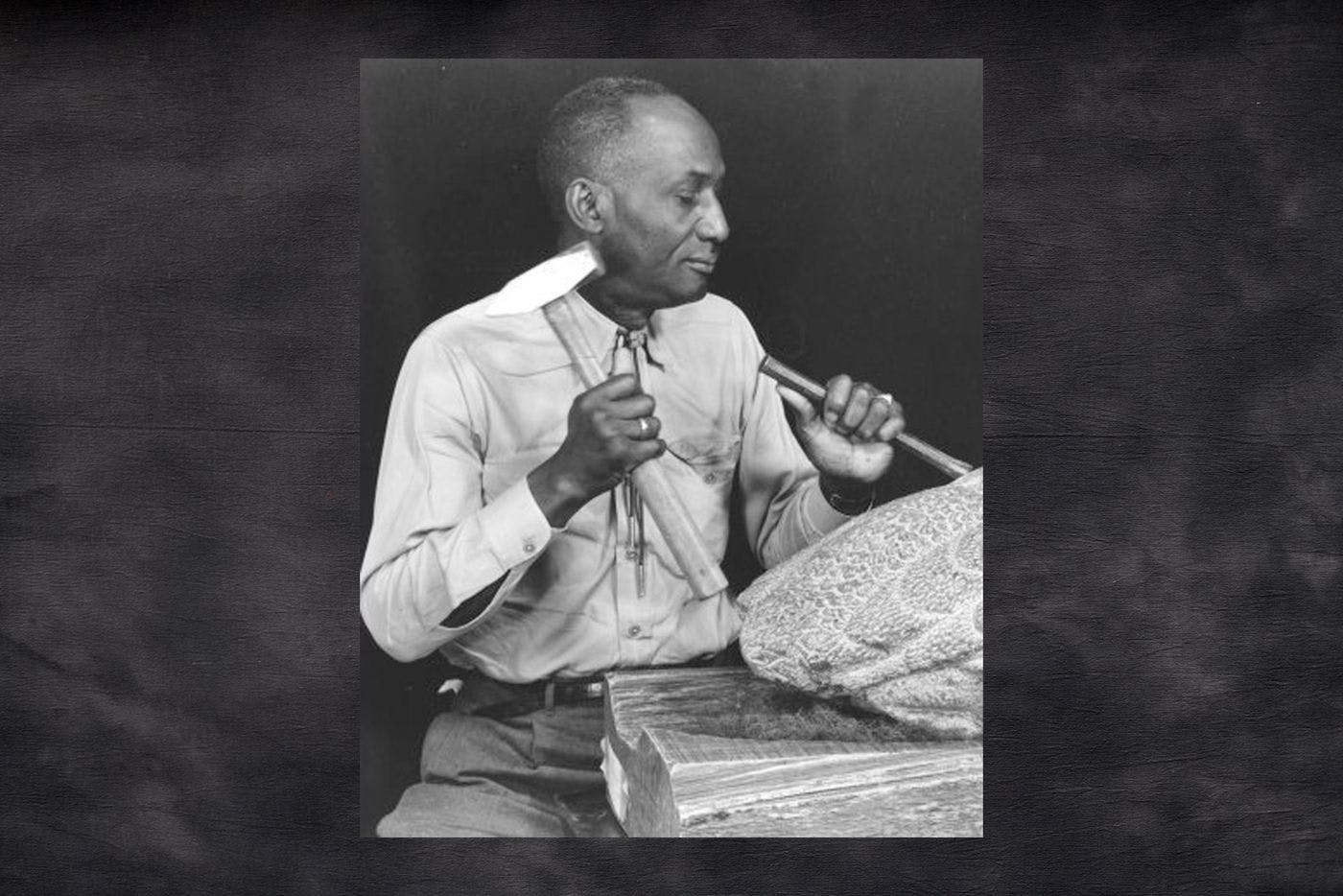

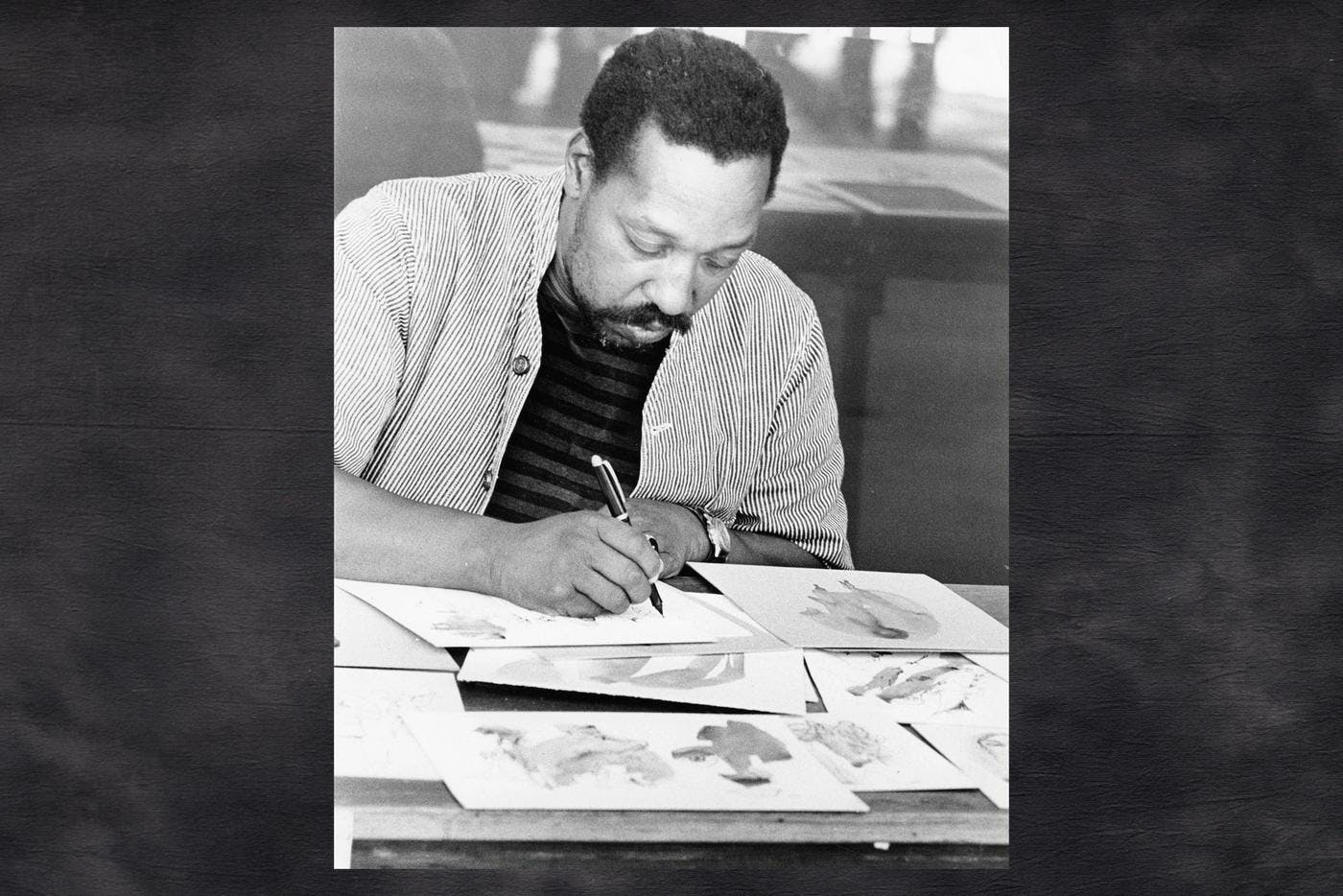

As a direct connection to the Harlem Renaissance, this often overlooked painter inspired generations of Seattle movers and shakers.

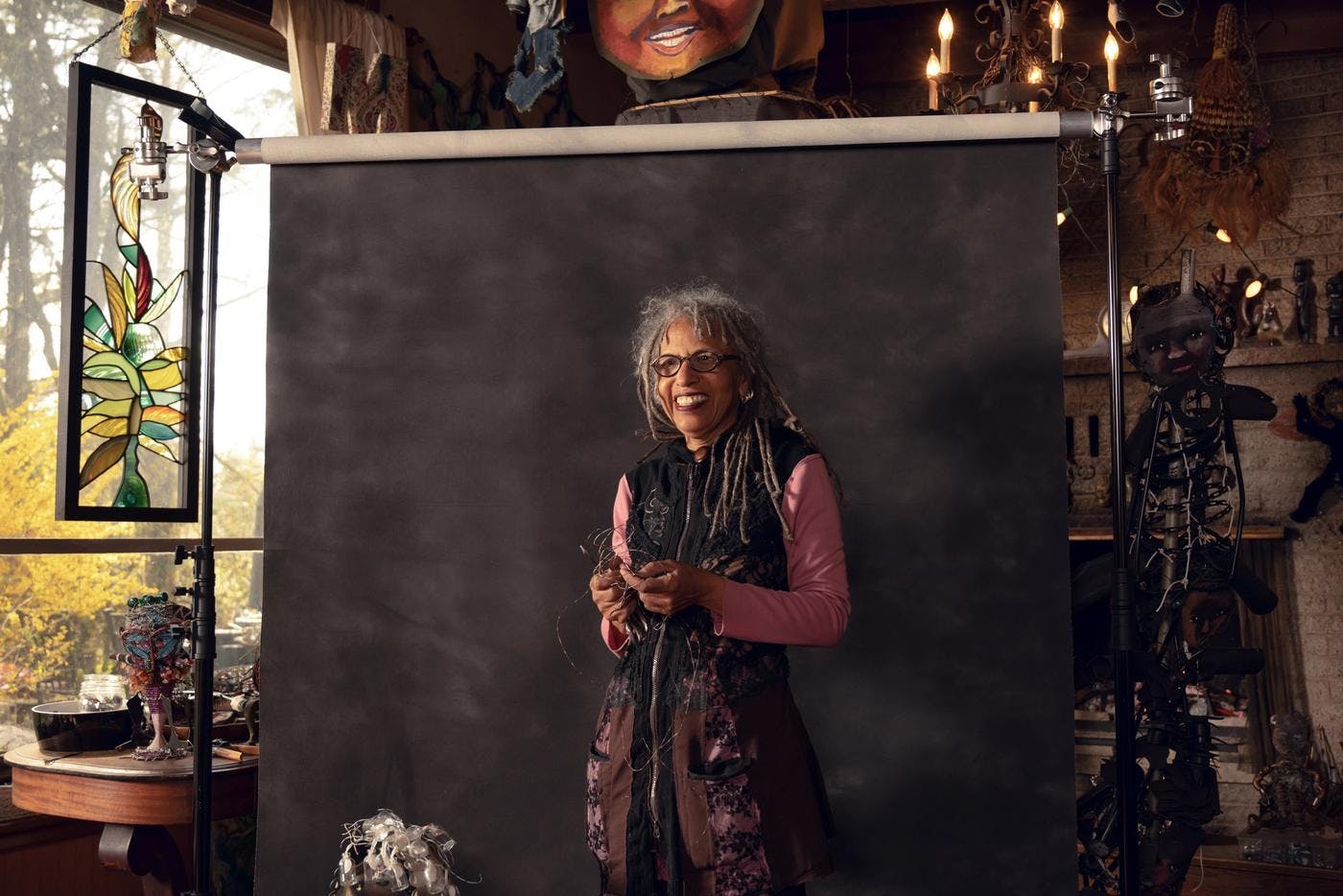

Salvaging old cloth and scrap metal, the longtime Seattle sculptor finds beauty in what’s discarded.

This Seattle artist channels his personal history and activism into vibrant murals and abstract paintings.

With meticulous skill and a communal approach, the longtime Seattle artist has cut her own path.

The first Black art instructor in Washington was an experimental artist ahead of his time.

Two curators separated by decades turn homes into galleries to support artists.

The influential art teacher uses books, found objects and photography to provoke thought and shift perception.

The late couple's house is now a cultural center that inspires the next generation.

The late director, producer, stuntman and teacher used film and video production to lift up the voices of Seattle’s Black community.

Through public murals, collaborative projects and custom sneakers, this artist is leaving her footprint on Seattle history.

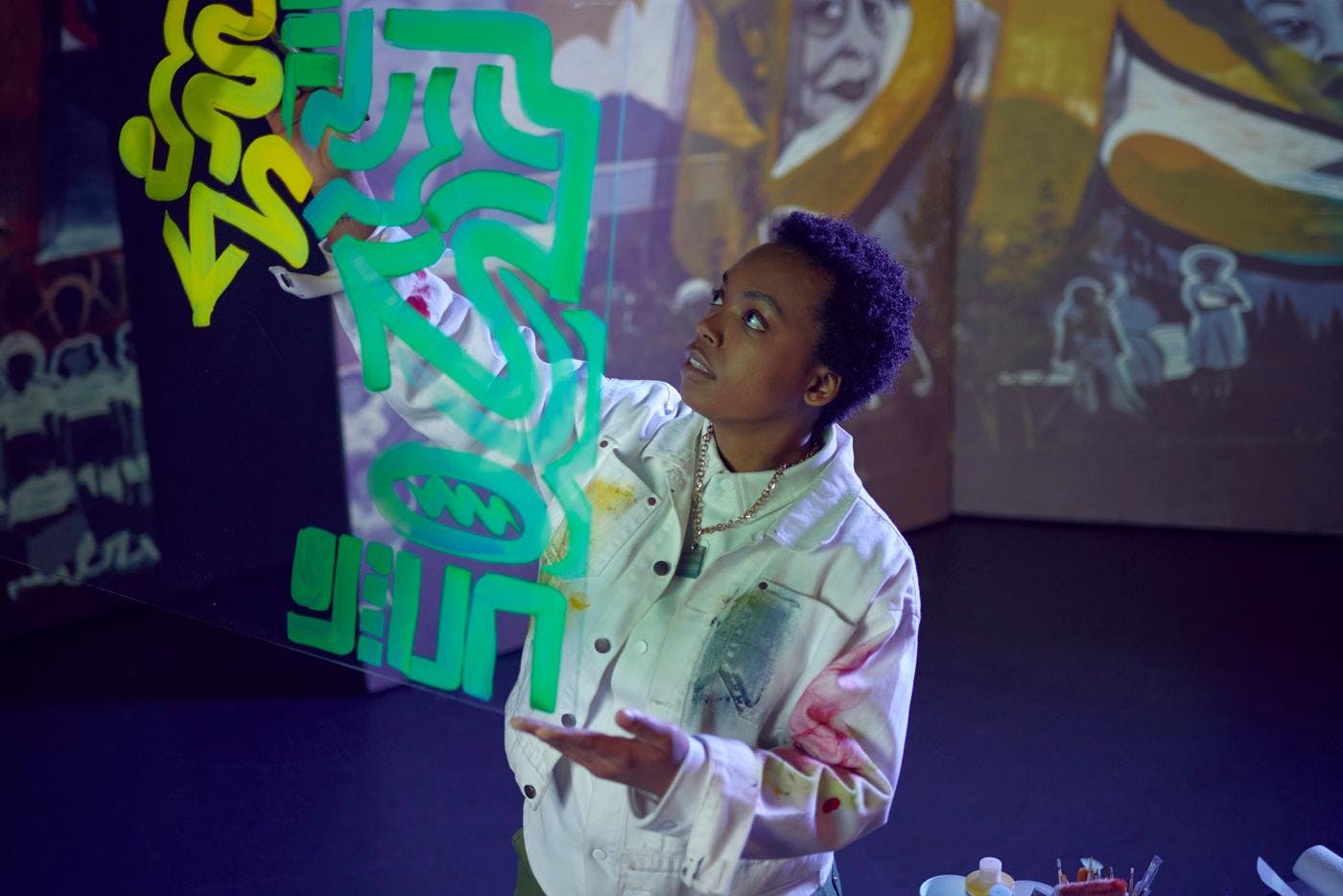

The curator, gallerist and artist is resisting the art establishment with bold immersive experiments.

From intricate portraits to multistory murals, the artists bring Black history and bold color to the cityscape.

Through ceramics, sculpture, jewelry and public art, the multifaceted artist makes Black history tactile.

Thanks to our Sponsors

Your support helps Crosscut create projects like Black Arts Legacies. Learn how you can help with a one-time donation or recurring membership.

Support Crosscut