Julian Priester

A fount of knowledge for the jazz community, the trombonist and living legend is shaping the next generation of Seattle musicians.

This beloved Seattle DJ found his divine calling in music — and in sharing it with others.

by Jas Keimig / June 7, 2024

The dance floor and church aren’t all that different.

Both serve as places of community, connection, personal enlightenment and poetic beauty. Electronic music and gospel speak to the spirit, and souls are lost and found on the grimy club floor just as often as they are between church pews.

No one understands this better than Riz Rollins, 70, who’s been DJing in Seattle for nearly half his life, serving as both parson and disc jockey for devotees of his club sets and KEXP radio shows. As a queer man who grew up in a religious family on Chicago’s South Side during the ’60s, Rollins knows more than a little about hellfire, devotion, divinity and music. But before he took up the mantle of DJ in the mid-’90s, he thought his life would turn out a lot different.

“I’m supposed to be a preacher,” says Rollins. “That’s what everybody expected in my grandmother’s church. They expected I was gonna be not just a preacher, but a pastor.” However, he was certain his sexuality would get in the way of that. “I knew when I was a young boy that I liked other boys — but I wasn’t supposed to,” he reflects. “I wanted to go steady, I wanted to have a boy I could go to the movies with."

For three decades, Rollins has been behind the DJ pulpit in clubs across Seattle as a venerated fixture at gay, hip-hop and electronic dance music parties, including “Flammable,” the world’s longest-running weekly house night, which started at Re-bar and is now at Chop Suey. Regardless of what he’s playing — be it funk, soul or house — whenever Riz is on deck, the dance floor turns into a place of communal liberation: Dancers aren’t simply two-stepping to the beat, they’re moving and grooving through whatever emotions or experiences they brought to the club, together.

Known for his mischievous air and warm soul, Rollins has been spinning records at KEXP since 1989, back when the call letters were KCMU. In 1995 he started the long-running Sunday night show Expansions, which started as a celebration of trip-hop and acid jazz and now features a broad mix of genres that skews underground and is hosted by a rotating set of KEXP DJs.

These days he’s also the selector on deck every Monday evening during drive time. Rollins also hosts live remote broadcasts every Martin Luther King, Jr. Day and Juneteenth, playing records alongside other Black DJs on two Black holidays. The music selection for these events is idiosyncratic, ranging from goth to funk.

“To me, it’s not so much about centering Black folks and Black music but to come to grips with the fact that all music is Black music,” he reflects. “We can play anything.”

Listening to a DJ Riz radio set is an ecstatic, amorphous experience — audiences are just as likely to hear the psychedelic stylings of the Grateful Dead as they are sexy club music by chanteuse Grace Jones. On all occasions, Rollins makes his broadcasts feel deeply personal, as if he and his listeners are just chilling in his living room.

“Somebody wrote in saying, ‘I don’t know what the theme is,’” Rollins says of a recent show on which he played the Altman Brothers, Beyoncé and Glen Campbell. “Ain’t no theme — get into it.”

Born in 1954, Rollins says his mom listened to jazz greats like Charlie Parker and Sonny Rollins when he was growing up. “Back in the day when Negroes couldn’t afford art, we put album covers up,” he remembers. “She had an album by Nina Simone called Pastel Blues and I was just totally transfixed by it. I don’t know how long it took before I actually played it, but I played it. I thought, ‘I’ve never heard anything like it.’”

His grandmother would take him to church during gospel’s heyday in Chicago, and every Sunday Rollins would listen to the church choir praise God accompanied by congas and a Hammond B3 organ. As a high schooler, he sang in the Operation Breadbasket Choir — an organization dedicated to improving the economic conditions of Black people and led by Reverend Jesse Jackson. As a participant, he listened to Jackson preach and met greats like Roberta Flack, who was a visiting guest of the choir.

After starting Bible college, Rollins eventually dropped out, then left Chicago at 25 when his family moved to Atlanta. He bopped around, spending time in Oregon before landing in Seattle in the early ’80s. For six years, Rollins did a whole lot of nothing, he says, feeling more than a little lost. An avid record collector since his teens, he worked in record stores and thought about his higher purpose.

“I was doing as much nothing as I possibly could. When I was 30, I looked toward heaven and told Jesus — ’cause a lot of this is really grounded in the way I was raised spiritually — ‘I’m too old for this. I’m a failure at 30.’ And God said, ‘Cool.’ I said, ‘Is it all right with you?’ He said, ‘Yeah, sure.’ ‘Is it all right if I do nothing?’ ‘OK,’” says Rollins. “So I did nothing and worked at Orpheum Records on Broadway. I had no aspirations. I really didn’t. There’s an old doctrine that says that when you’re empty like that, then the divine can fill you up.”

And the divine did indeed fill him up. In 1989, when Rollins was 35, a friend named Paula was promoting a night at Re-bar, a closed but still beloved gay bar in the Denny Triangle. She asked Rollins to DJ after seeing him play records at James Brown birthday parties he hosted at his friend Elaine Bonow’s Belltown studio (and continues to host annually, 35 years later). Around the same time, KCMU music director Don Yates asked Rollins to DJ on the radio.

At first Rollins demurred both offers; he’d never played a club nor on the radio. But eventually he accepted both gigs. He would go on to spin at Re-bar regularly until its 2020 closing and continues to DJ on KEXP to this day, broadcasting mostly from his home in Hillman City.

As an elder DJ who still gigs and routinely has to stay up until 2 a.m. in clubs packed with sweaty bodies itching to dance, Rollins has to do a different sort of preparation for a show than when he was in his 30s — a disco nap is imperative, for one. But he intends to keep spinning records over the radiowaves and in the club for as long as possible. Rollins does, after all, have a higher power on his side.

“When you adopt a jazz model of creativity, then longevity is different,” says Rollins. “Not only can you do it for the rest of your life, you could do it beyond and in a certain sense, you can get better. All the jazz greats, John Coltrane, Miles Davis, Sarah Vaughan, Ella Fitzgerald, got better. They could perform until they went home to be with the Lord. That’s the longevity that I claim.”

Black Arts Legacies Season 3 is made possible in part thanks to support from 4Culture.

Black Arts Legacies Writer

A fount of knowledge for the jazz community, the trombonist and living legend is shaping the next generation of Seattle musicians.

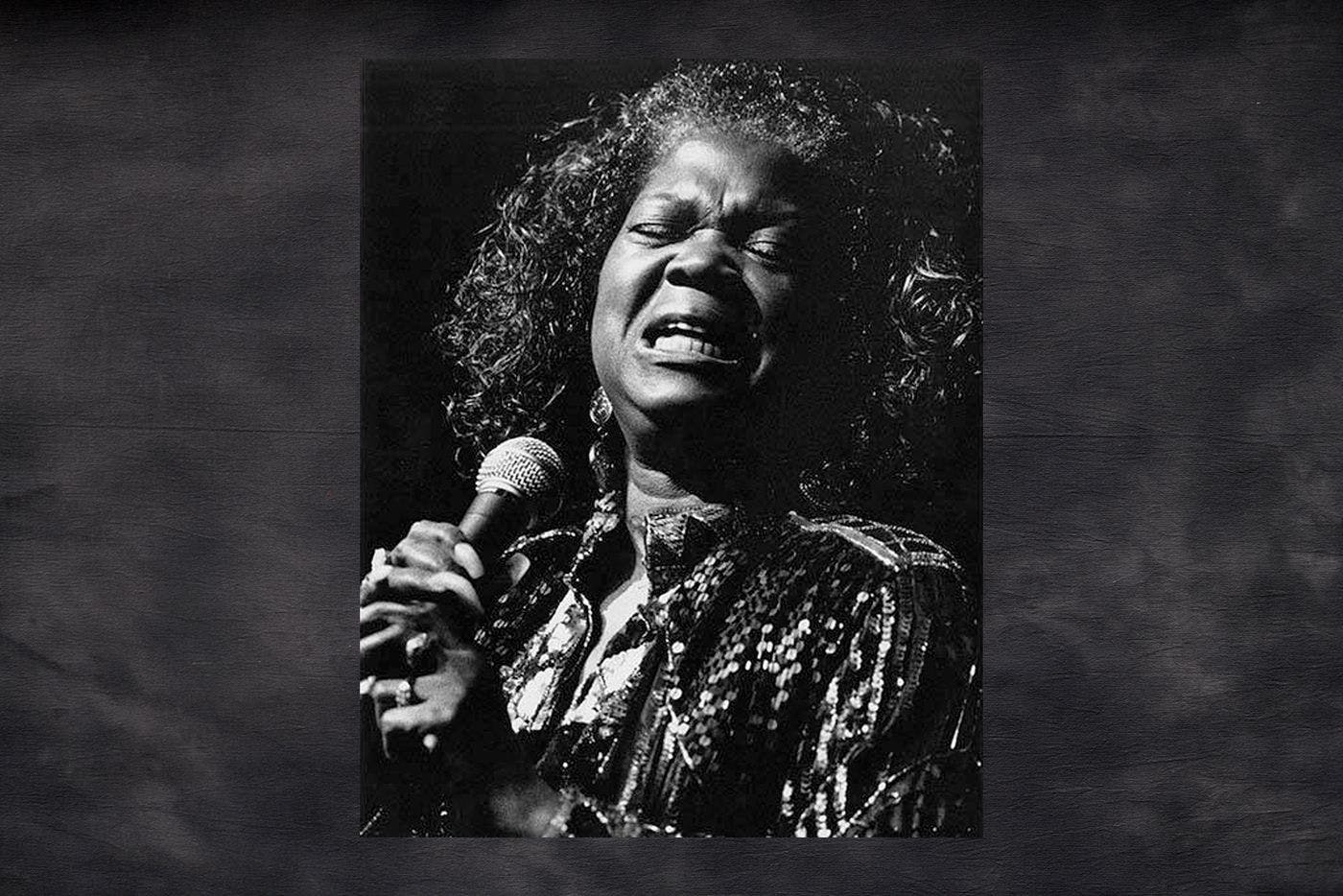

With a voice like ‘honey at dusk,’ the singer helped put Seattle’s early jazz and blues scene on the map.

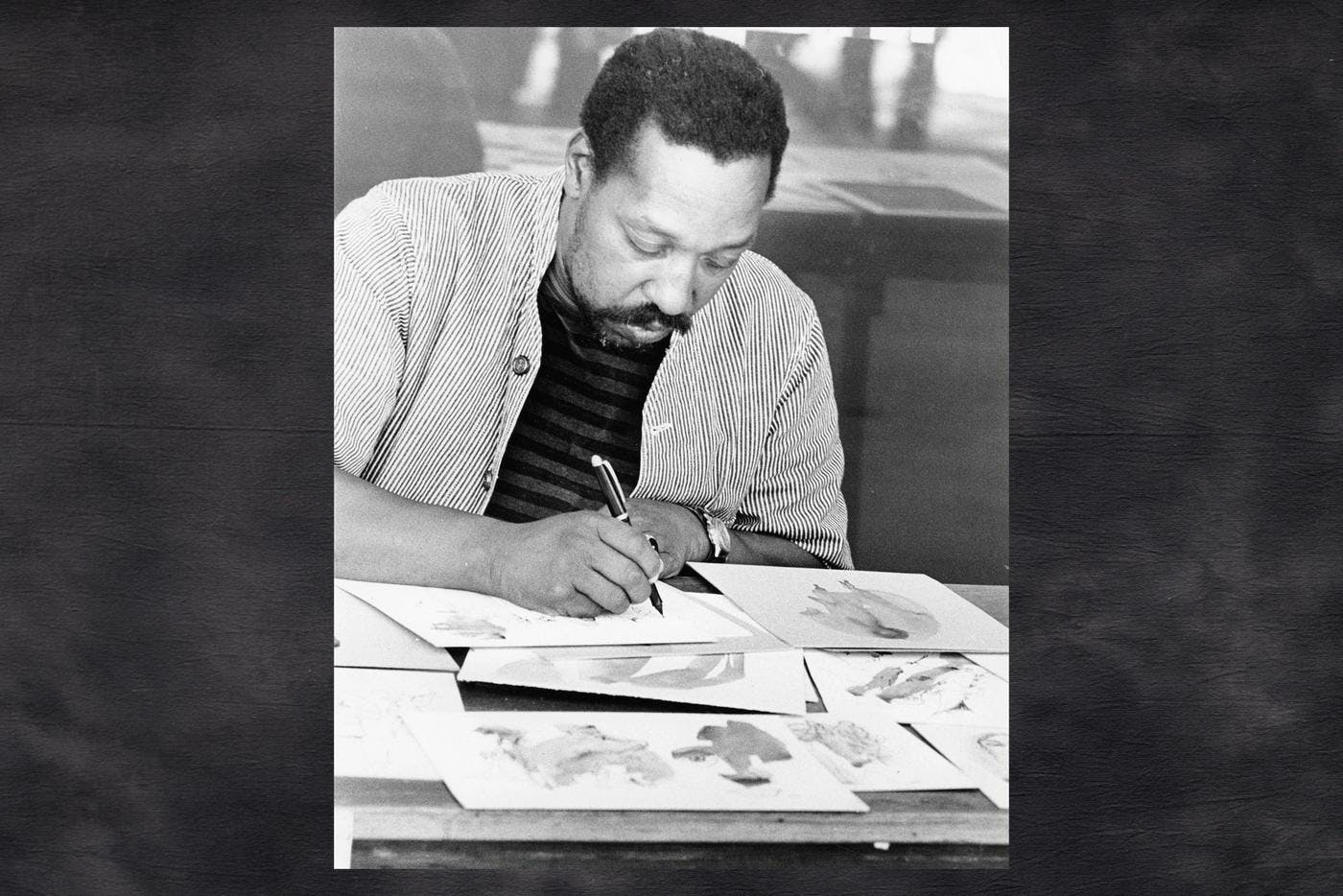

The first Black art instructor in Washington was an experimental artist ahead of his time.

For three decades, this Seattle DJ electrified the airwaves, paving the way for future Black radio personalities.

A poet at heart, this soul singer/songwriter is inspiring the next generation of Seattle musicians.

As a founder of Digable Planets and Shabazz Palaces, the Seattle rapper has pushed hip-hop to the outer limits.

The Seattle rapper keeps his memories of the Central District alive with vivid lyrics and a jazz sensibility.

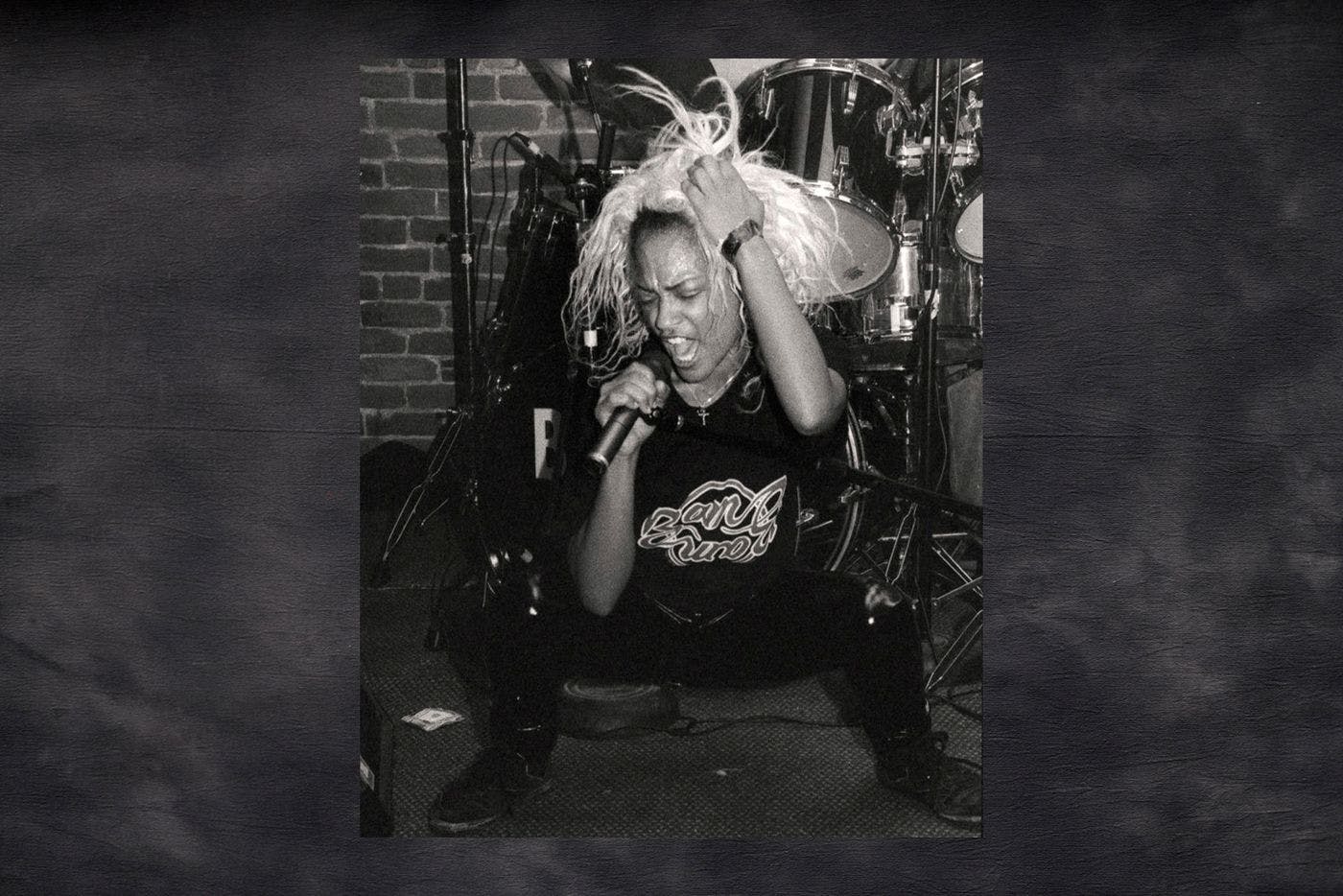

A pivotal figure in Seattle’s proto-grunge scene, the Bam Bam singer has been long-overlooked. Now, rock history is being rewritten.

The talented multi-instrumentalist uses music to string communities together.

Meet a Seattle music pioneer and the band carrying the legacy of Northwest rock forward.

Composing meditative music with a looping pedal, this Seattle cellist has charted her own sonic path.

Thanks to our Sponsors

Your support helps Crosscut create projects like Black Arts Legacies. Learn how you can help with a one-time donation or recurring membership.

Support Crosscut