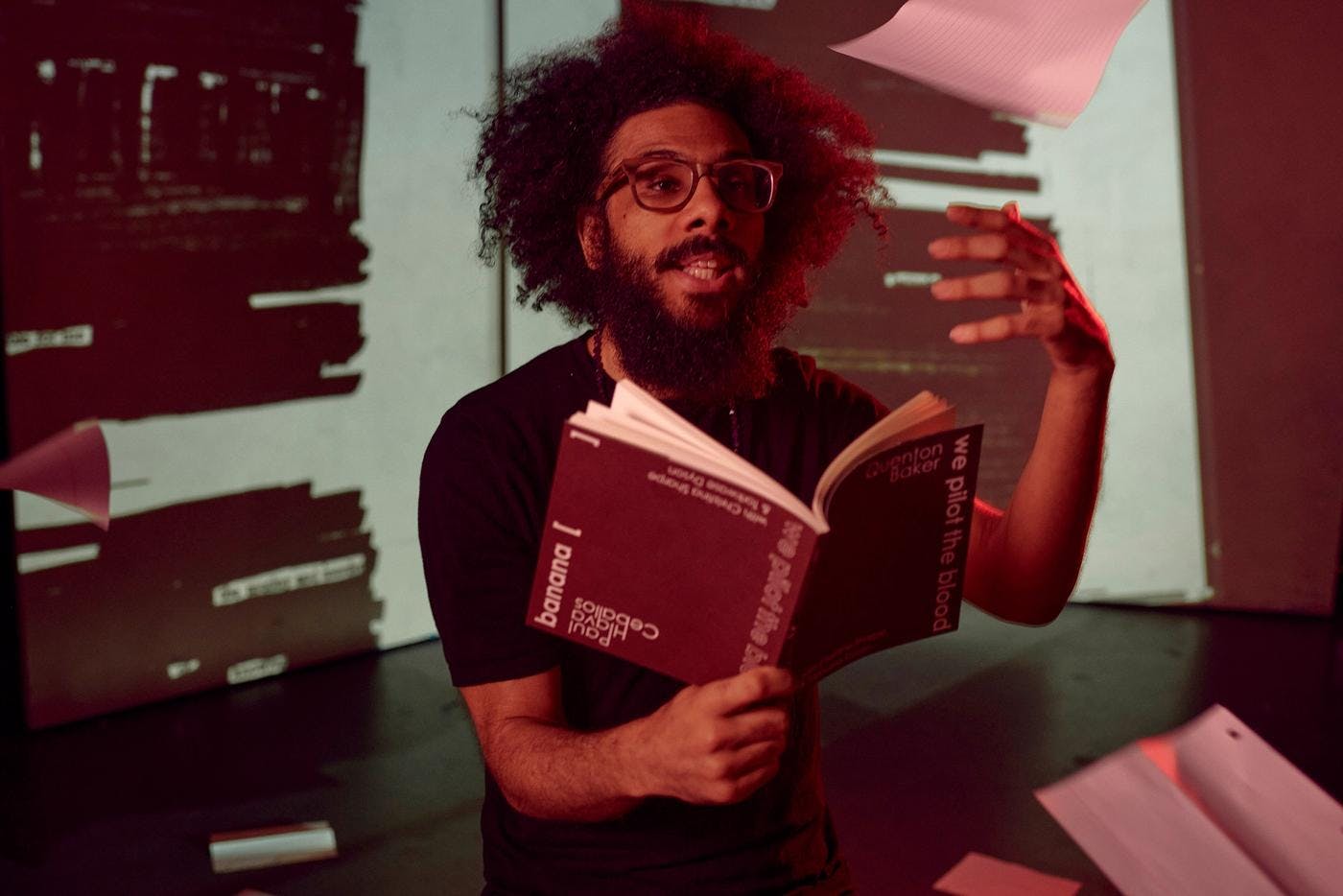

Jourdan Imani Keith

Seattle’s Civic Poet draws from nature and art to craft poems that embody the experience of living within the city’s many communities.

Inspired by the verdant beauty of South Seattle, this poet inscribes Blackness onto the landscape.

by Jas Keimig / June 21, 2024

One afternoon in graduate school, poet Luther Hughes looked out at the flat, tree-lined streets of St. Louis — and something felt off. The crows that congregate on power lines, flood the sky and chill in murders at parks in Seattle were nowhere to be seen.

“I was like, where the hell are all the crows at? What is going on?” Hughes remembers. “I realized it wasn’t necessarily the crows I was missing. It was actually Seattle.”

All at once, Hughes experienced a deep ache for their mossy PNW hometown — and a bit of a corvid obsession. For this poet, crows hold a lot of symbolism: death, Seattle, freedom, Blackness itself. They are the throughline in “Tenor,” the opening poem of Hughes’ 2022 debut collection, A Shiver in the Leaves, which explores queer desire and violence against Black people: “The empty crow/untethers/something in me: a feral/yearning for love.”

Born at Providence Hospital on Cherry Hill in 1991, Hughes grew up in Skyway and attended Renton High School, where they performed with a local dance team and started to explore their love of poetry, an interest sparked in church.

“I heard the choir director read a poem about birds, connecting birds to group mentality or group thinking. I was blown away at 12 years old,” Hughes recalls. “That’s when I knew poetry can be more than just what I was learning in school.”

As a teen, they’d write poems that they would share only with friends or keep for themself. Never imagining it could be a full-time endeavor, Hughes took journalism classes in community college as a way to keep studying writing and honed their poetry skills at open mic nights.

But not until they matriculated at Columbia College in Chicago did they take their interest in poetry more seriously, reveling in the city’s strong poetry scene and earning a bachelor’s degree in creative writing and poetry.

After jumping directly into a poetry MFA program at Washington University in St. Louis and graduating in 2018, Hughes moved back to Seattle, where they have since cultivated a substantial audience both locally and online.

Their work — including two books and individual poems published in Paris Review and Orion Magazine — has received a slew of prestigious recognition: a Cave Canem fellowship, several Pushcart Prize nominations, a 92Y Discovery Poetry Prize, and a shoutout from The New Yorker.

Bucking the poet-writing-alone-in-their-room stereotype, Hughes is deeply invested in community. They founded both Shade Literary Arts, an online poetry journal dedicated to publishing queer writers of color, and Lue’s Poetry Hour, a monthly Substack that grew out of a series of Twitter threads in which Hughes recommended poetry based around a single theme or identity, highlighting work by genderqueer and Latinx poets, often about nature or romance.

Hughes also co-hosts The Poet Salon podcast alongside Seattle poets Gabrielle Bates and Dujie Tahat, interviewing both locally and nationally recognized bards such as Danez Smith, Ada Limon and Quenton Baker over a drink. Together, the Poet Salon trio dive deep into their guests’ work while sipping bourbon, gimlets or Sprite.

Guests also read a favorite poem — and then the entire pod geeks out over the rhyme, syntax, images, meaning and memories connected to it. Since 2022 the podcast has been on pause as the co-hosts figure out their next steps, Hughes says, but the Poet Salon archive remains an accessible and engaging glimpse into a poet’s process.

Through their poetry and community work, Hughes creates space for Seattle poets — specifically Black poets — to recognize their worth.

“I want all of us to really understand that our legitimacy does not come from national acclaim, it does not come from white spaces or non-Black spaces,” Hughes says. “It comes from each other.”

Influenced by their childhood spent in the South End among the greenery and the cherry blossoms, Hughes weaves Blackness into the Seattle landscape. Sometimes that takes a more figurative form, like in “Mercy,” in which they reckon with what it means to be a citizen of this country:

Peeking through the clouds, Mt. Rainier, with

its white tank top, several cities to glare

upon, and a moral blue sky to angle into,

must love by now to be American.

Other times, Hughes draws from Seattle’s history of violent anti-Blackness. In “In Seattle,” they meditate upon the 2014 murders of two gay Black men, Dwone Anderson-Young and Ahmed Saïd, deftly intertwining the deep, embodied pain of the news with their surroundings:

There is [blood] parading the streets, I reply. The

market bricks with whirs and wears the violent

churning of noise on its lips like balm.

I drink a cup of coffee, sitting on a bench

overlooking The Sound.

There is so much blue.

In the crows, the mountains or the streets, Hughes illuminates the hidden connections between ourselves and our environment. Their work helps us see who we are.

Black Arts Legacies Writer

Seattle’s Civic Poet draws from nature and art to craft poems that embody the experience of living within the city’s many communities.

An accomplished poet expands her art practice and meets new challenges along the way.

How this Seattle artist uses poetry to illuminate the persistence of the past in the present.

The former Seattle and King County poet laureate exalts the magnetic power of Black women using her verse and voice.

Thanks to our Sponsors

Your support helps Crosscut create projects like Black Arts Legacies. Learn how you can help with a one-time donation or recurring membership.

Support Crosscut