Edna Daigre

A dance teacher beloved by generations of Seattle students, this longtime movement maven believes breath is life.

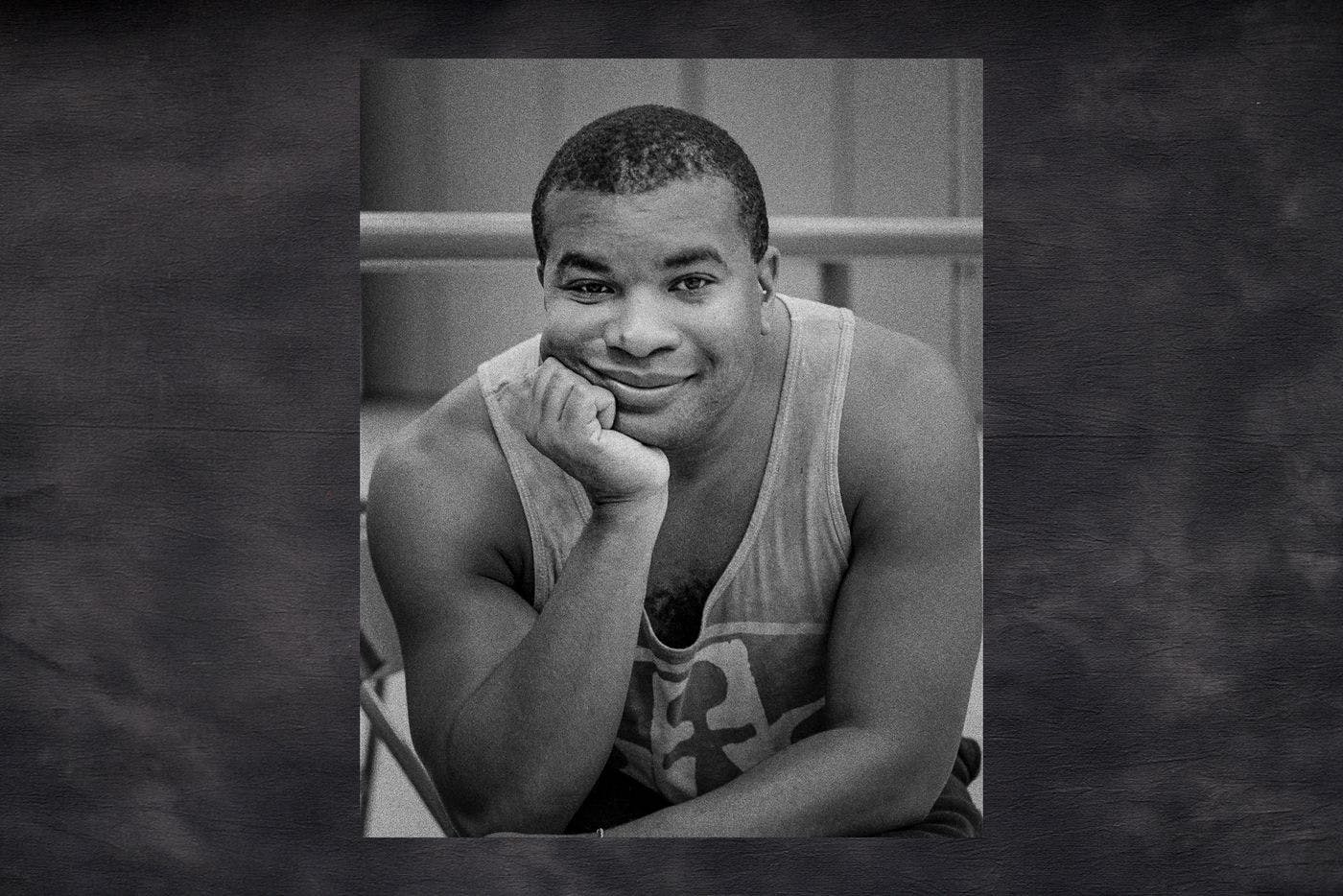

Pacific Northwest Ballet’s first Black woman soloist dances across disciplines.

by Jas Keimig / May 2, 2023

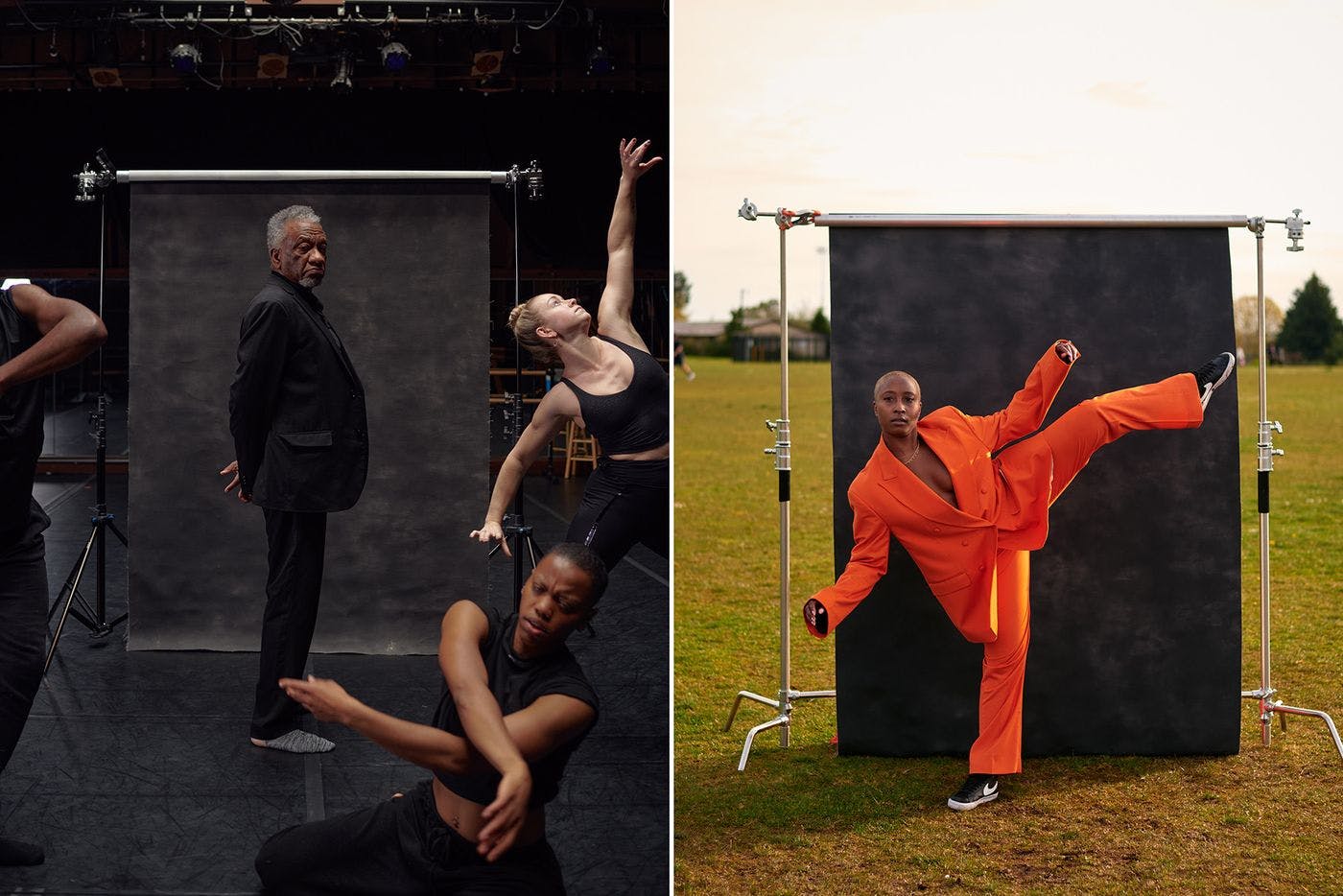

Before the November 2022 premiere of The Seasons’ Canon, Pacific Northwest Ballet artistic director Peter Boal stood in front of McCaw Hall’s sumptuous red curtain and called Amanda Morgan onstage.

The lanky ballerina listened with joy on her face as Boal sang her praises as a “mesmerizing” performer and committed mentor to student dancers. Finally he made his big announcement: Morgan had been promoted to the rank of company soloist — the first Black woman in PNB’s 50 seasons to claim that title.

“I’m still grappling with the fact that I’m a soloist, to be honest,” Morgan says nearly five months later. “I just wanted to get there. Not just for myself, but for all these people that need to see that we can excel in this art. It didn’t really hit me until the day I got promoted. I couldn’t stop crying.”

With this promotion, Morgan stands alongside another famous first: Kabby Mitchell, PNB’s first Black dancer, who joined the company in 1979 and also rose to soloist.

At 26, the dancer, ballerina, activist and choreographer is a force of generative energy and collaborative drive. In 2020 Morgan took to the Seattle streets to protest George Floyd’s murder and support the Black Lives Matter movement, and soon after she called for internal diversity changes within PNB. During the pandemic lockdown, she choreographed dance films in her apartment building and the water tower in Volunteer Park.

Now she balances her PNB commitments with choreographing her own work, co-hosting the artistic-process-focused podcast Let’s Workshop It and connecting artists across the city through her organization The Seattle Project (more on that later). She’s even — slowly — working toward getting her Bachelor’s degree in arts management through a PNB partnership with Seattle University.

“I want to keep evolving as an artist, and a way for me to do that is to continue to create, grow, try things out and experiment,” she says.

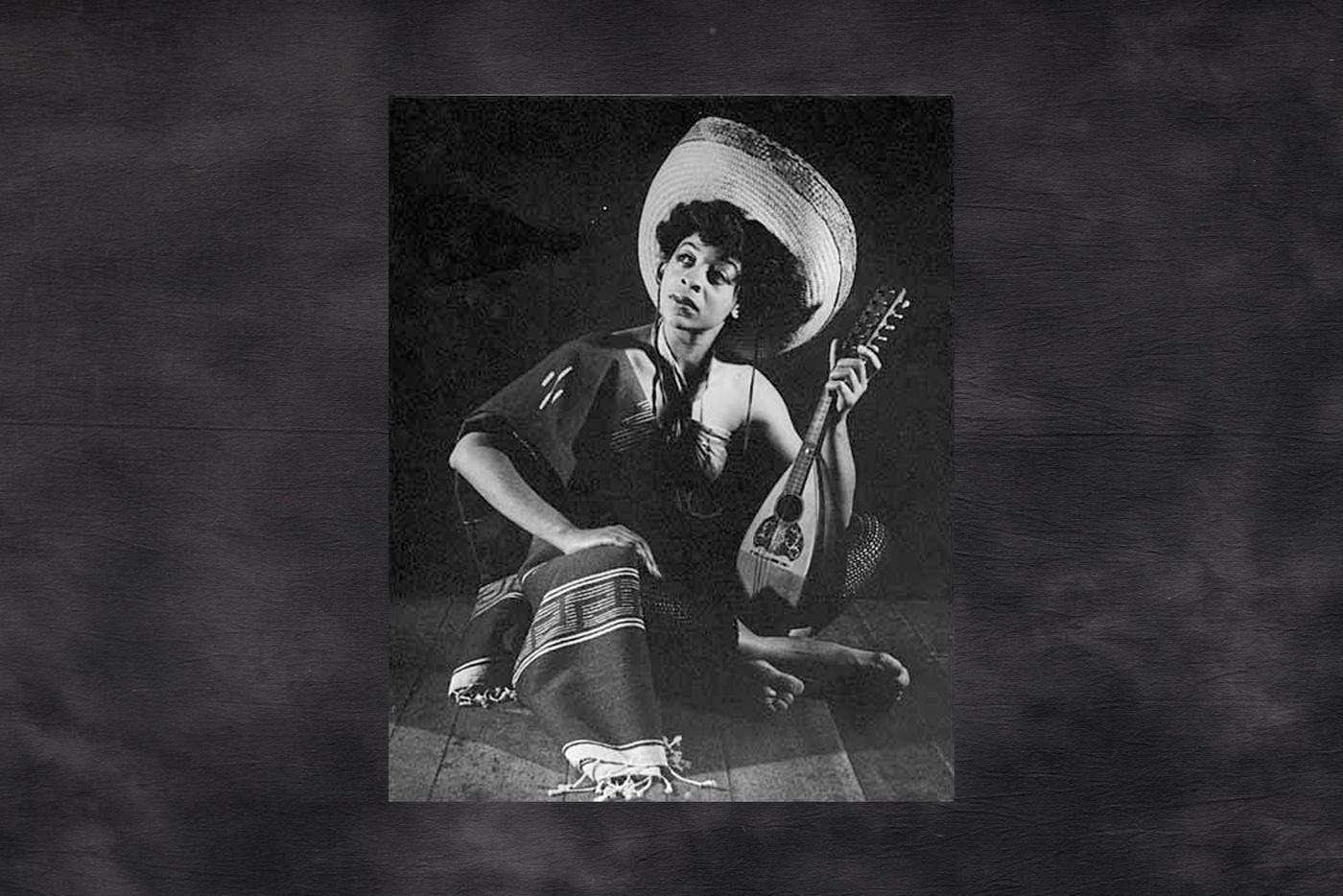

Morgan grew up in Tacoma, the daughter of a Dominican mother and Puerto Rican-Jamaican father who moved the family from New York City just before her birth.

When Morgan was 2, her mother enrolled her at Dance Theatre Northwest, just outside of Tacoma. In 2011, at 14, she received a full scholarship to Pacific Northwest Ballet School, where Boal first saw her dance.

“She had a very challenging piece created for her for the year-end school performance by our teacher Le Yin,” Boal says. “Le just kept discovering Amanda’s strengths and abilities and putting them front and center. He really gave her some impossible things to do, and she didn’t realize they were impossible. She just did them.”

Though Morgan excelled in her PNB program and later in the school’s professional division, she struggled with being the sole Black ballerina in classes. “It was hard to hear people either undermine me or underestimate what I could do just because of what I looked like,” she says, explaining that Black dancers aren’t often given a chance to perform softer, more feminine roles.

“It's not anything malicious, but because people haven't seen someone that looks like me do certain roles, they're automatically not going to think of me for those roles,” she says.

In those low moments, Morgan found mentorship from former PNB dancers Karel Cruz and Lindsi Dec, who were also tall and Latinx. “They were very encouraging of me and my career even when I was a student,” Morgan says. “That definitely influenced me, to know that there were people in the company who believed in me.”

In 2017 Morgan was tapped for a spot in PNB’s corps de ballet. In traditional ballet the corps must look and move uniformly; however, it’s precisely Morgan’s departures from those (petite, white) standards that make her so exemplary: the precision of her long legs, the powerful way she leaps across the stage.

As a new soloist — one step below the highest company rank, principal dancer — Morgan will have more opportunities to take on those famously feminine, quintessentially “ballerina” roles like the Sugar Plum Fairy in The Nutcracker, which she danced in December 2022. But since her promotion, Morgan feels preshow pressure in a new way.

“Most lead roles that I do will be the first time a Black woman is doing them in PNB, or even in history, depending on the part,” she says.

Morgan’s creative practice doesn’t begin and end at McCaw Hall. Having always wanted to make art with visual artists, musicians, filmmakers and poets, in 2019 she founded The Seattle Project, a platform for the city’s interdisciplinary artists, specifically BIPOC and queer people, to connect with dance and movement artists and with one another.

“The themes I focus on in my work outside of PNB usually have to do with minority identities and queer representation,” she says. “Most of the people I work with are younger artists, so it feels exciting to be able to shift culture as a generation of artists.”

Morgan and Seattle Project collaborators like Randy Ford, Nia-Amina Minor, Christopher D’Ariano and Ashton Edwards bring dance out of the theater and into people’s lives. Sometimes this manifests as short dance films that use notable Seattle locations as a stage — from the viewpoint at Kerry Park to the Martin Luther King, Jr. mural outside Fat’s Chicken and Waffles in the Central District. Other times Seattle Project has staged live performances in Seward Park, Seattle Center, and nontraditional performance spaces like Great Jones Gallery on Capitol Hill.

“I've watched the network of creatives expand over time, offering a space for movers and media makers to play and experiment, which is especially necessary for BIPOC and LGBTQIA+ artists in our community,” says Rana San, Northwest Film Forum artistic director and a Seattle Project collaborator. “Amanda is one of the most prolific artists making intermedia work in Seattle right now.”

Morgan is currently choreographing Chapters, her first full-length contemporary dance work, which will premiere at Northwest Film Forum in May. The piece explores the idea of “home” for different Black femmes, and features Minor, Edwards, Akoiya Harris, Kenya Shakoor and Morgan herself. “It’s a very vulnerable [piece] for me,” she says.

Always a collaborator, Morgan asked local designer Janelle Abbott to create costumes and sets. Visual artist Barry Johnson is contributing a short behind-the-scenes documentary about Chapters and about making art in community with other Black people.

“The Seattle Project has been a vessel to help grow myself as an artist and arts leader,” Morgan says. “By being more experimental and intentional in my work outside of PNB, I have very much been that way within PNB.”

As a dancer who grew up as one of the only Black ballerinas in her company, Morgan is acutely aware of the stakes. Her newest role as PNB soloist remains her priority. But her rigorous, technical work at PNB primed her to push herself to new creative frontiers.

“I can feel in my bones that Seattle’s going through an artistic renaissance,” she says. “I feel excited to be a part of that and hopefully bring different types of artists together. We have the opportunity to cultivate [the Seattle dance community] and shape how we want it to be.”

Black Arts Legacies Writer

A dance teacher beloved by generations of Seattle students, this longtime movement maven believes breath is life.

Sixteen years after he first discovered tap, this Seattle dancer is finding his place in the lineage of an art form with deep roots in the Black community.

The Pacific Northwest Ballet’s first Black dancer went on to co-found a treasured performing arts school in Tacoma.

The dancer, choreographer and instructor broke barriers and influenced generations of artists.

For these dancer-choreographers, social engagement takes center stage.

Thanks to our Sponsors

Your support helps Crosscut create projects like Black Arts Legacies. Learn how you can help with a one-time donation or recurring membership.

Support Crosscut