Jourdan Imani Keith

Seattle’s Civic Poet draws from nature and art to craft poems that embody the experience of living within the city’s many communities.

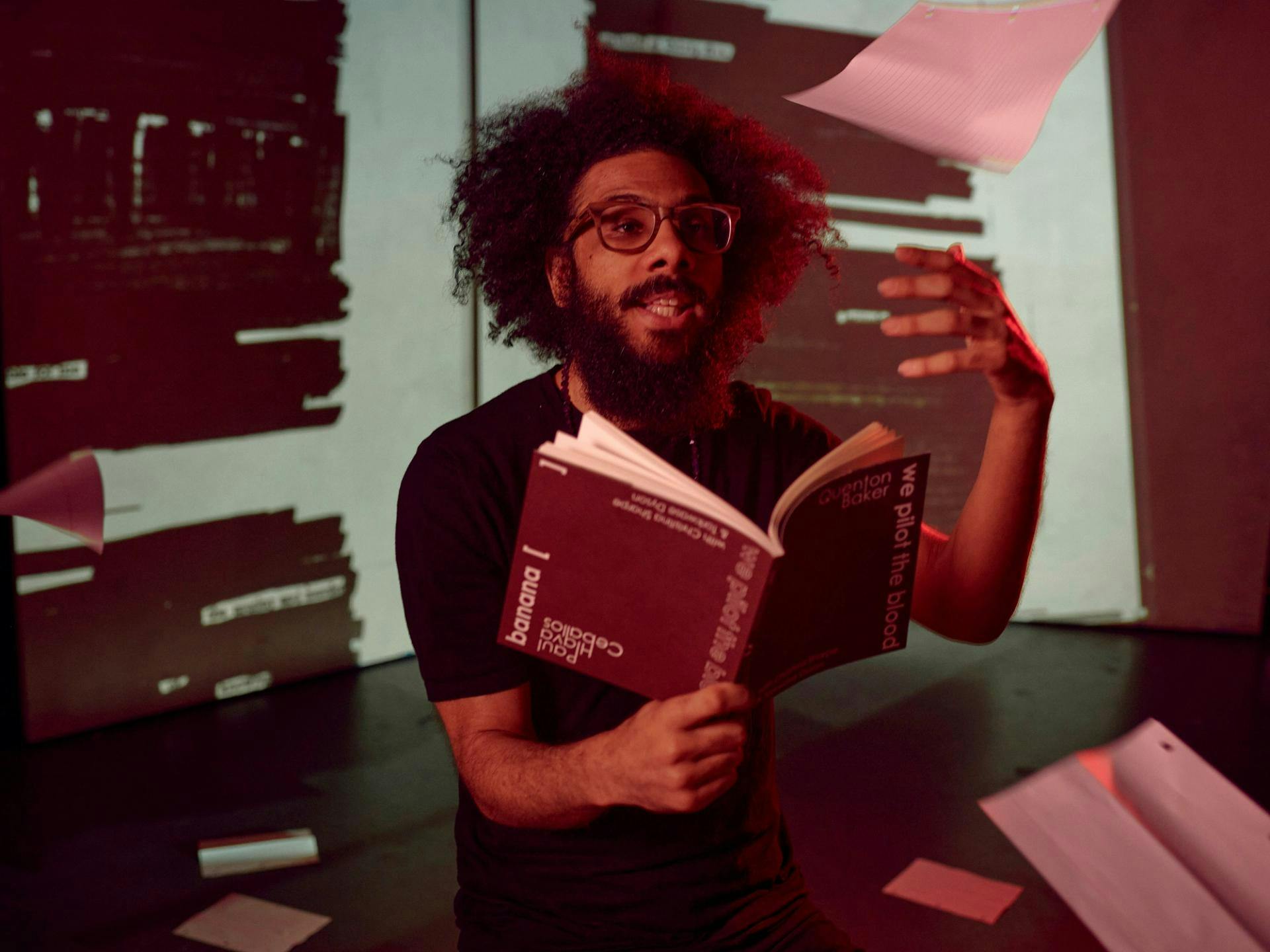

The Seattle artist uses poetry to illuminate how a Black past persists in the present.

by Jas Keimig / April 25, 2023

In 2015 Quenton Baker was reading Walter Johnson’s 1999 book Soul by Soul, an investigation of the slave trade in antebellum America, when they stumbled upon a brief mention of an unfamiliar event: an 1841 revolt aboard the ship Creole, in which enslaved people successfully overtook the brig and escaped to freedom in the Caribbean. “I was like, What is this?” Baker says. How had the history buff never heard this story before?

After a largely fruitless inquiry to the U.S. Office of Records, Baker reached out to a University of Wisconsin professor (who had included the Creole story in one of their courses) and obtained a 19th-century U.S. Senate document — one of the few contemporaneous accounts of the revolt. But it included only depositions of angry white slavers and crew members, who misshaped this incredible tale and drowned out the voices of enslaved people.

To channel their strong emotional response, Baker turned to erasure poetry, a form they'd previously not had much interest in. But this document seemed to demand it.

“I was really mad reading the document,” Baker says. “I wanted to redact or do an erasure because I felt like this document is emblematic of the civic level of erasure of Black folks.”

Using a black Sharpie as a scalpel, Baker began blacking out the words of white slavers and shaping the rest into thoughts they imagined those enslaved people might have spoken or felt. Tilling the soil that would later become their 2023 book, ballast, Baker turned this documented violence and historical indifference into a channel to the past:

it has been impossible for me

the mutiny and murder

of

Knowing

“These people are buried beneath this document,” Baker remembers thinking. “If I chip it away, will something come out that's an echo or a ghost or a haunting of them?”

As a poet Baker orbits the “afterlife of slavery,” a term coined by historian and theorist Saidiya Hartman to express how chattel slavery’s legacy persists in the lives of Black folks. While focusing on stories willfully skimmed over by historians, Baker is careful not to project agency backward where it didn’t exist.

“It's part of the poet's responsibility and part of the artist's responsibility to not let these people be forgotten,” Baker says, citing an influential Claudia Rankine interview on her poetic philosophy. “And in that lack of forgetting also not revictimizing or retraumatizing them.”

In their 2016 book This Glittering Republic, Baker evokes George Stinney Jr., a Black child executed by the United States in 1944. They underscore the boy’s childlike innocence by imagining him licking an ice cream cone in “Drip”: Take your time/enjoy the fat chill/of each lick/and don’t let nobody rush you.

In “Museum of Man,” Baker sits with Sarah Baartman, a Khoikhoi woman exhibited in a freak show in 19th-century Europe, reflecting on her exploitation and humanity. There will never be a moon/or a season free from the heritage/of your harvested skeleton–/but you’re more than dismemberment/aren’t you?

Born in Seattle in 1985 to a Polish-Jewish mother and a Black “country boy” father from Illinois, Baker grew up on North Beacon Hill and went to Garfield High School in the Central District. “The south end is my home forever,” they say. It’s where they nursed their love of reading: “I was in the library all the time … I know those librarians got tired of me.”

From their teens through their mid-20s as a student at Seattle University, Baker performed for crowds along the West Coast as Intro (short for “Introspective”) in the rap group Gray Matters. But by age 25, writing crowd-pleasing rhymes didn’t artistically satisfy. “I want to create art with language that, for me, has some type of meaning or purpose,” they say.

In 2010 Baker left hip-hop and started life as a poet, getting their MFA in poetry at the University of Southern Maine. But music left a permanent mark on their artistry: “The concept of rhythm, the concept of flow — all those things I try to maintain [now] in a different way.”

Baker explores difficult subjects in all of their work, illuminating aspects of being Black in America, perceptions of Blackness and the lasting effects of racism. In addition to their four published books of poetry, Baker’s poems have appeared in publications such as Poetry Northwest and The Rumpus. In the past several years, Baker has received a coveted Cave Canem fellowship; two nominations for The Pushcart Prize; the 2019 Robert Rauschenberg Artist Residency; and 2017 Jack Straw and 2021 NEA fellowships.

This is all to say: They stay busy.

They also continually experiment, iterate and push their work forward. In 2016 Baker won the James W. Ray Venture Project Award, which gives winners the opportunity to mount their own show at the Frye Art Museum. In 2018, an exhibit of the Creole Senate documents — blown up, printed directly on the wall and redacted using paint rollers — opened at the Frye. By working at this massive scale, Baker allowed viewers to physically confront the work, making the poetry, and therefore the voices within, more tangible.

“We’re cut from the same cloth, in that we don’t necessarily write about Black joy,” Anastacia-Reneé, a fellow poet and Black Arts Legacies alum, says of Baker. “It doesn’t mean that we don’t have love. It doesn’t mean that we don’t have joy … They write about historical atrocities that I think need to be talked about.”

Poets like Anastacia-Reneé, who Baker says is like a big sister, keep them rooted in Seattle. “Community has given me permission to do a lot of things,” they say. “Seeing people be their full courageous selves in their work really pushed me to do the same thing.”

That doesn’t mean living in Seattle is easy. Surviving in this city as a Black poet is difficult, even though it’s their hometown.

“Seattle has always been full of people and politicians well-versed in progressive etiquette but lacking in terms of actual care for marginalized peoples,” Baker says. “It's definitely been accelerated by the tech presence and the massive influx of capital, but it still feels like the same city in a lot of ways. Just with a lot fewer Black folks to provide a counterbalance, or an escape.”

Baker is one artist providing that necessary counterbalance. Their practice brings forth both the beauty and the terror of being Black in the United States, provoking wonder and a bit of a shiver. They may focus on the long shadow of the past in the present, but their work also contains nuggets of how to survive in the future, laid out in poems like “Inversion”:

I am cold-shouldered time,

misused spirit made chattel,

crude ballast.

I cannot be buried–

I carry the sunset in my mouth.

Black Arts Legacies Writer

Seattle’s Civic Poet draws from nature and art to craft poems that embody the experience of living within the city’s many communities.

An accomplished poet expands her art practice and meets new challenges along the way.

The former Seattle and King County poet laureate exalts the magnetic power of Black women using her verse and voice.

Inspired by the verdant beauty of South Seattle, this poet inscribes Blackness onto the landscape.

Thanks to our Sponsors

Your support helps Crosscut create projects like Black Arts Legacies. Learn how you can help with a one-time donation or recurring membership.

Support CrosscutLoading...