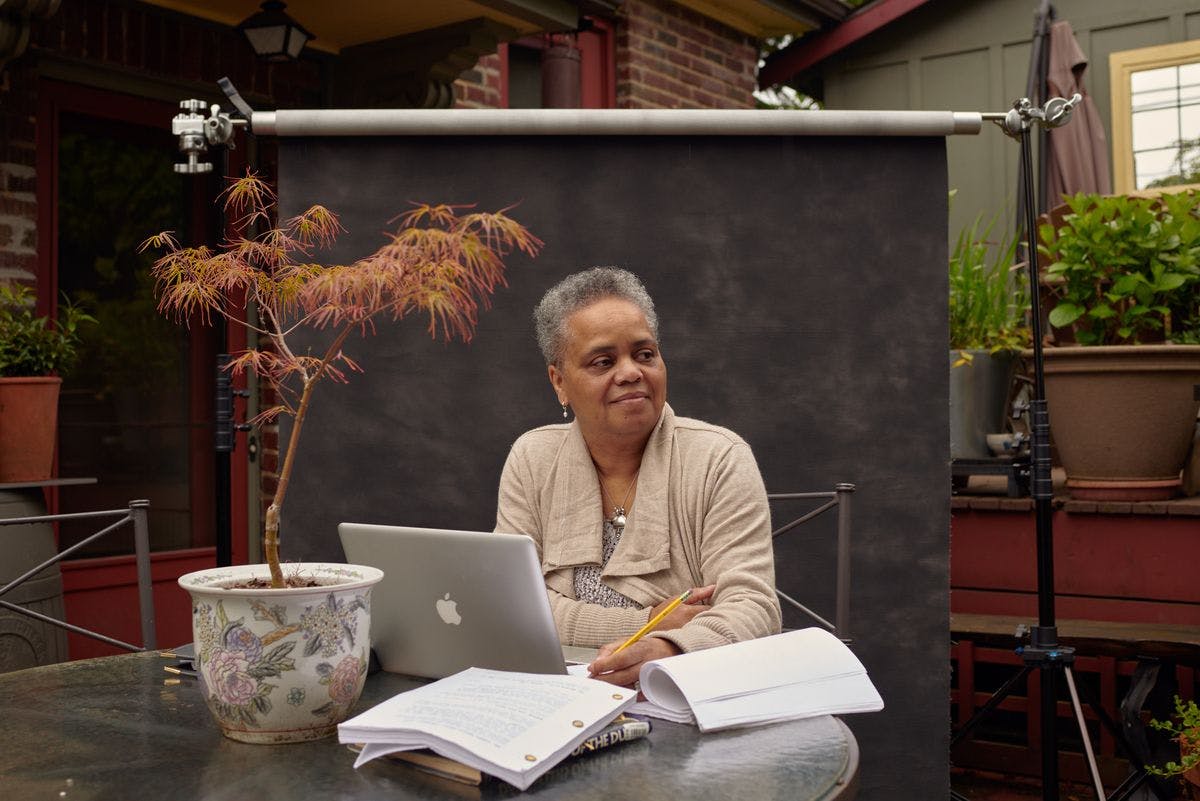

Cheryl L. West

Seattle Rep’s most-produced living playwright tells complex Black stories with integrity and poetry.

After landing on the stage unexpectedly, this Seattle actor/director’s 50-year career played a major role in the city’s Black theater scene.

by Jas Keimig / April 30, 2024

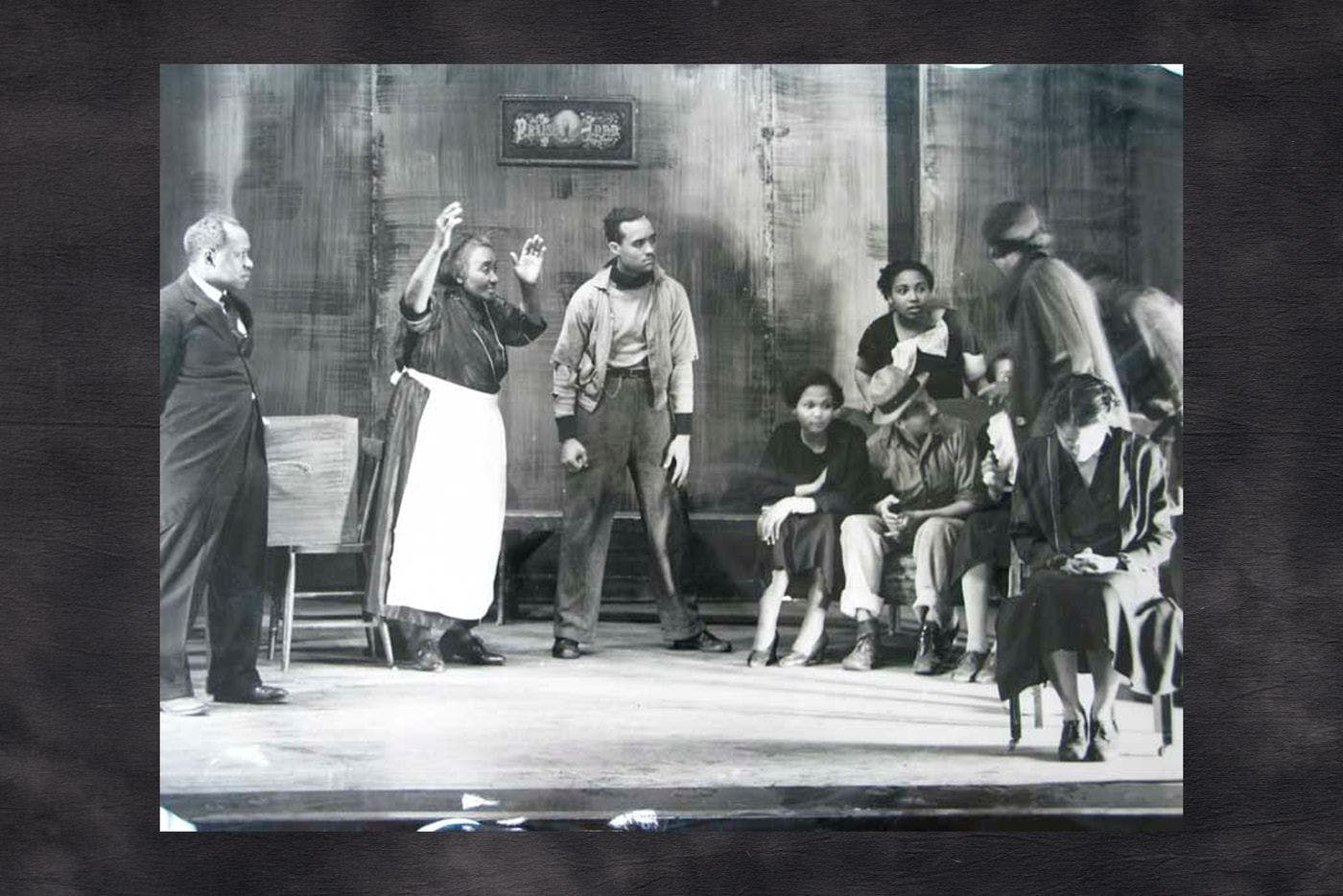

In 1973, with exactly zero acting experience, Tee Dennard walked into an audition at Black Arts/West in Seattle’s Madrona neighborhood, hoping to meet some single women. The theater was casting for J.E. Franklin’s Black Girl, a play about a young woman who dreams of escaping the confines of her home life to become a ballet dancer.

As expected, “When I opened the door, there were wall-to-wall beautiful Black ladies!” Dennard recalls. What he didn’t expect was to get cast as an understudy for the role of Mr. Herbert, the grandmother character’s boyfriend.

“I didn’t have no intentions of becoming an actor, but after dealing with Black Girl and seeing how things went, I got bit by the bug,” says Dennard. “I’m blessed enough to have a little talent.”

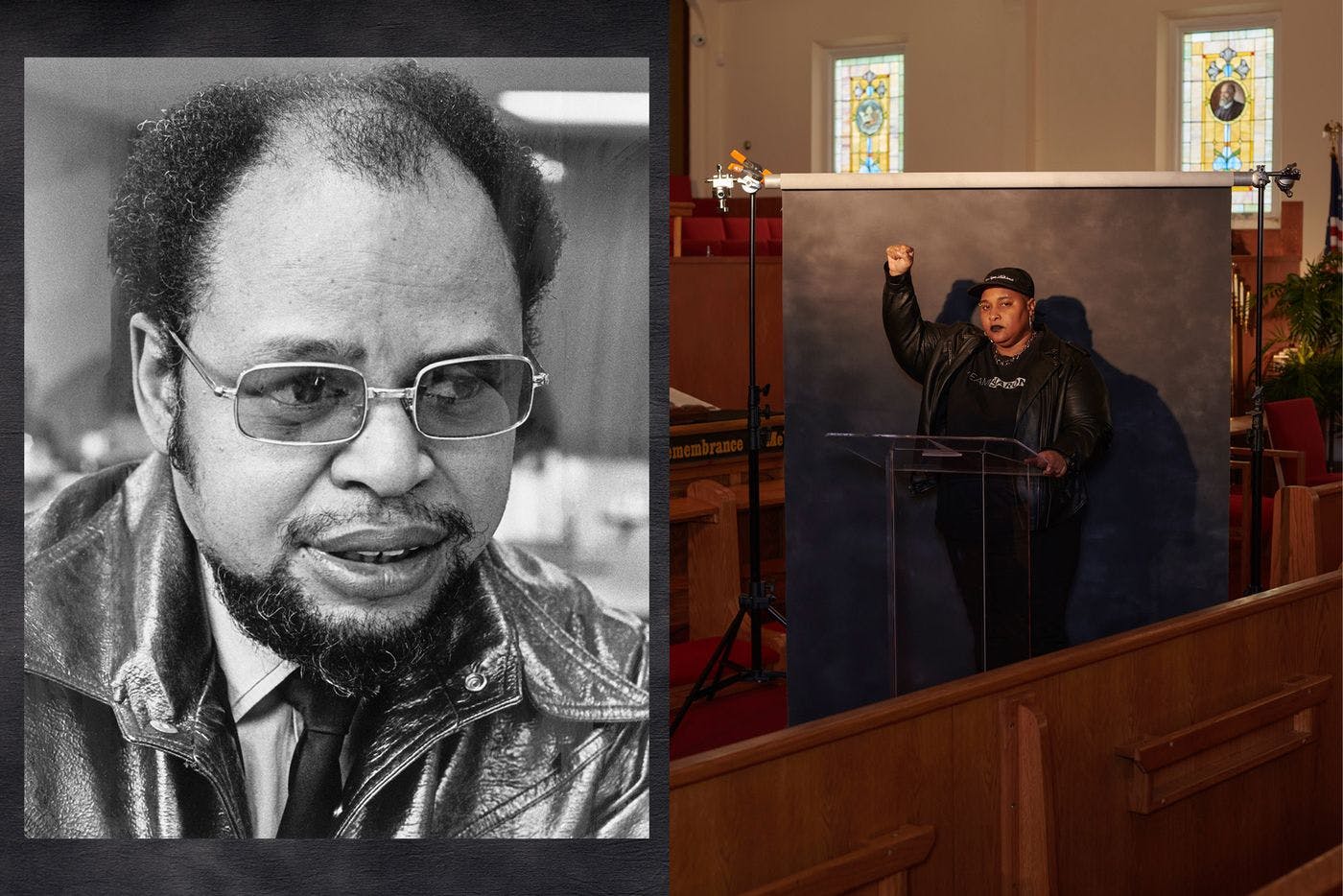

From then on, Dennard became deeply involved with Black Arts/West, then located on 34th Avenue and East Union Street in a building that still stands. (It’s now home to a Glassybaby shop.) The influential former Black-focused company had been founded in 1969 by Douglas Q. Barnett as a means of addressing the political, social and economic realities of the Black community.

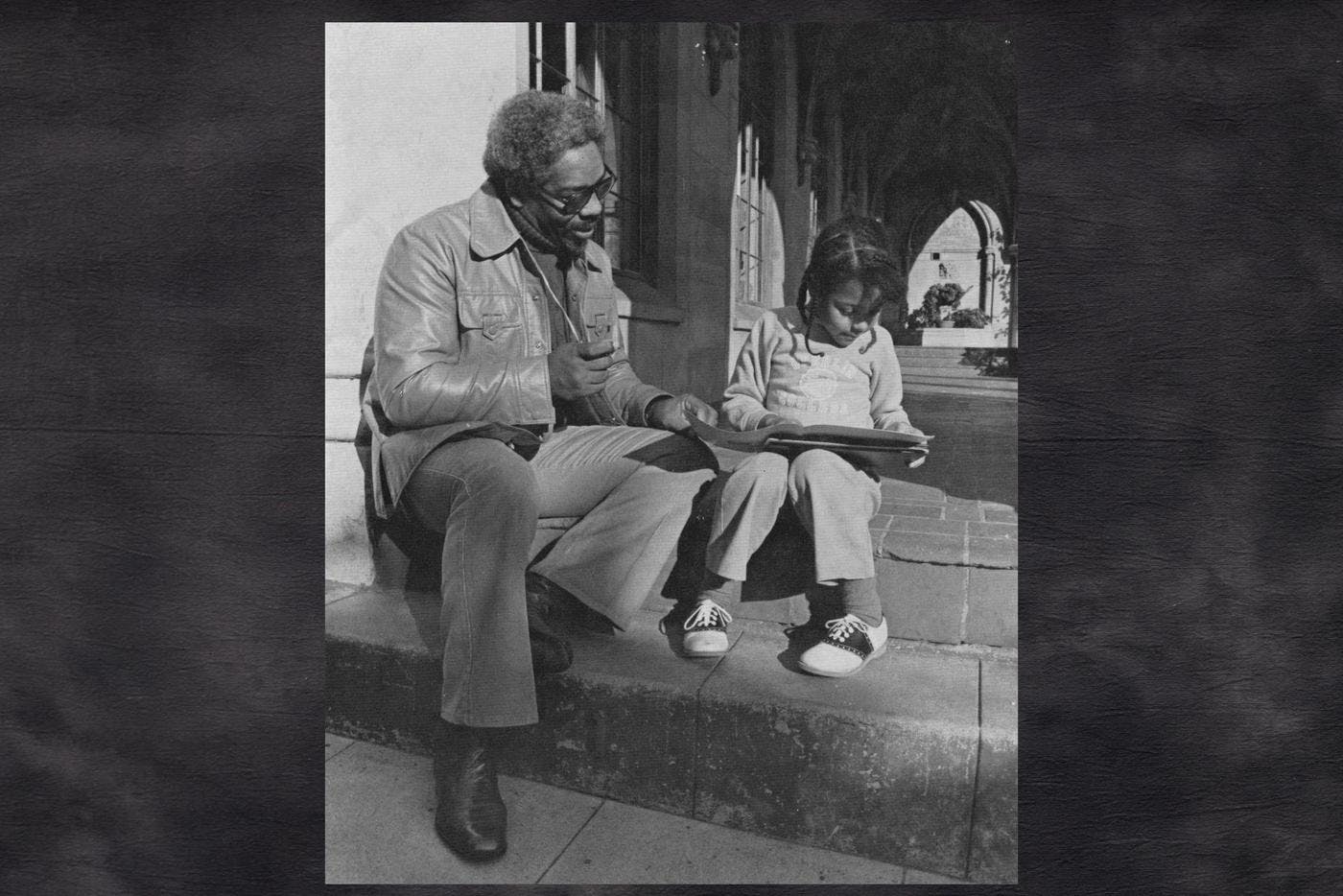

In the 50 years since that first fateful audition, Dennard, now 80, has been a powerful presence on the Seattle theater scene, a prolific actor known for bringing a certain gravitas to his performances, no matter how big or small the role. Among them: Walter Lee Young in A Raisin in the Sun and Rev. Purlie Victorious Judson in the musical Purlie, both at BA/W in the 1970s.

After BA/W’s closure in 1980, Dennard continued to appear in and direct productions on various stages around town and slowly picked up more gigs in both local and Hollywood films, such as 1982’s An Officer and a Gentleman and 1984’s Starman.

Teotha Dennard, Jr. was born in Ashburn, Ga., in 1943, the third child of four. His name, Teotha, is a nod to his paternal great-great-grandmother’s Choctaw heritage, he says, noting that he, his father and his grandson are the only Teothas he knows.

When he was 4, Dennard and his family moved to Gary, Ind., then a booming steel town. His uncles and other relatives worked in the steel mills, but Dennard’s single mother struggled to make ends meet. He remembers, as a sophomore in high school, hearing her cry at night because of their dire financial situation.

Dennard wanted to do something about it.

“I had a friend and we decided to go into the military. I had to have my mom sign for me because I wasn’t of age,” he remembers. “My plan was to go into the military and send my mom an allotment. That would be one less mouth for my mom to feed and she would only have to deal with my [younger] brother.”

So in 1961 Dennard entered the Air Force—“one of the best decisions” he ever made, he says. Dennard’s time in the military gave him and his family a solid financial foundation. Upon his return to the United States from active duty in Germany in 1965, Dennard worked for a couple of years in the steel mills of Gary and eventually got married. In 1968, he and his then-wife decided to move closer to her family in Washington state.

“We came into Seattle on the bus at night across the floating bridge and the moon was hitting Lake Washington,” he says. “It was so beautiful and so magical. I was sold right then on Seattle.” He and his wife ended up divorcing soon after, but Dennard decided to stay in Seattle for good.

By 1973, Dennard had settled into the rhythms of Seattle life. While working as a social worker for the state’s welfare department, he ran into an acquaintance, Seattle actor Charles Canada, who dared him to try out for a play: the Black Arts/West production of Black Girl.

“I didn’t know what an audition was. I didn’t know what Black Arts/West was. I never thought about theater or any kind of arts in my life!”

After getting his big break in that production, Dennard “jumped in with both feet,” taking acting workshops and internalizing the acting techniques of big-name Black actors like Sidney Poitier as well as BA/W collaborators such as Ian Foxx and Buddy Butler, the company’s artistic director. He continued to appear in small parts like Fun Loving in the comedy Five on the Black Hand Side, but it was his role as Walter Lee Younger, a man desperate to become wealthy and lift his family out of poverty, in Lorraine Hansbury’s seminal A Raisin in the Sun in 1976 that made him decide to take acting seriously.

The play’s director, David Connell, pushed Dennard to his limit. “He brought something out of me that I didn’t know I had inside me,” Dennard reflects. “I had to dig into the particular psyche of that character, I had to become that character.” BA/W’s production of Raisin proved to be a hit, earning standing ovations almost every night.

When the show closed, Dennard signed up for theater classes at the University of Washington. “I was like a sponge. I soaked up whatever I could and whatever that would make me a better actor and a better person,” says Dennard, though he ultimately left UW to pursue acting outside of school. “I realized through trial and error that being an actor takes a lot of discipline.”

Using his tall stature and authoritative voice, Dennard brought a thoughtful depth to his roles. In 1978 he earned rave reviews in Miguel Pinero’s prison play at the Ethnic Cultural Center Theatre, Short Eyes, as Ice, a boisterous prisoner with a humorous screed about Jane Fonda and masturbation. The Seattle Times called the moment “one of the most accomplished and breathtaking scenes in recent Seattle theater history.”

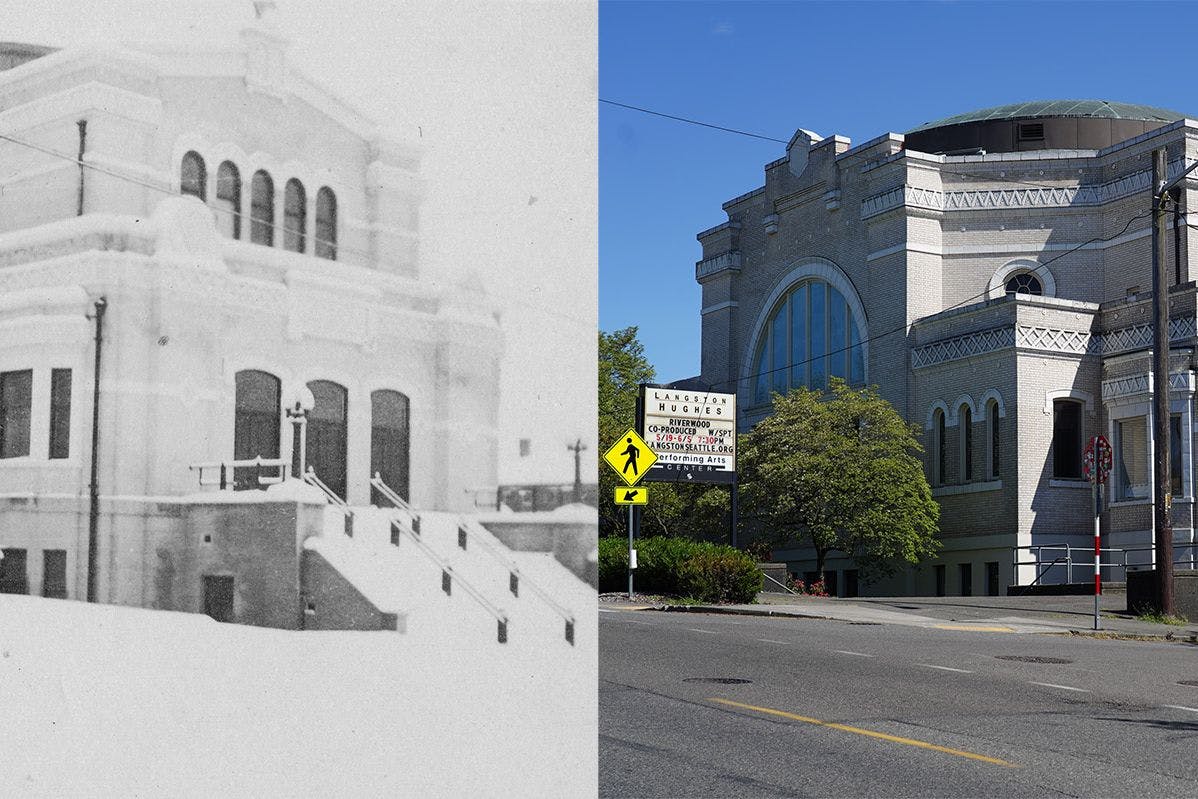

As he became known for solid performances, Dennard slowly started directing as well. In the late 1970s he helmed productions at BA/W such as the drama The First Breeze of Summer and the comedy Happy Ending at the Langston Hughes Cultural Arts Theatre.

“I had a reputation of not being the easiest person to work for because I didn’t have the theater training,” he remembers. Malcolm West, an actor who worked alongside Dennard for decades on plays like Simply Heavenly at BA/W and What the Winesellers Buy at Seattle Group Theatre, recalls Dennard’s approach as straightforward, to the actors’ benefit.

“He’s so real. He won’t pull any punches with you. He’ll tell you like it is and he’ll almost make you want to do what you think you can’t do or you don’t want to do,” says West. “It’s a talent manipulation. Because here’s the thing — a lot of times you’re working with someone and you see they have it, you see they can do it. But they, for some reason, will hold back and not let it out and not let it go. Well, he knows how to reach in there and hold on to you.”

In 1978, BA/W executive director Doug Johnson asked Dennard to become the company’s artistic director. Dennard happily accepted, eager to continue supporting the organization that had given him so much.

But the company’s glory days were behind it. Both Dennard and Johnson struggled with a frustrated audience who did not come out to productions anymore because they deemed BA/W out of touch, unprofessional and unvaried in its play selection, focusing too much on plays of a political nature. The National Endowment of the Arts — a primary funder — gave BA/W an ultimatum: raise $100,000, which the NEA would match, or shut down.

After failing to rouse enough support, Dennard says he and Johnson decided to close Black Arts/West in 1980.

“I get a little emotional even talking about it because it was such an institution. It was one of the only Black theaters in the country that had been in existence for over 10 years and thrived in its own space,” Dennard says.

Throughout the late 1970s and into the ’80s, Dennard continued to act on stage but also made several television and movie appearances. Repped by legendary Seattle talent agent Lola Hallowell, he earned his first credit in 1976: a part in the TV movie The Secret Life of John Chapman. Notably, he also appeared alongside many other BA/W actors in Seattle producer Nate Long’s South by Northwest series about Black pioneers in the Pacific Northwest.

But his biggest role was in An Officer and a Gentleman, which was shot in Port Townsend and starred Richard Gere and Louis Gossett Jr. Dennard played a “Dilbert Dunker” instructor teaching aspiring aviators how to survive a water impact.

“I’m really proud of that moment because it took an ensemble. I only had a small part but it was a very important, integral part of the movie,” says Dennard. “That’s my claim to fame.”

He’d go on to appear in 13 more films, among them the Debra Winger vehicle Black Widow and the TV movie The Last Innocent Man alongside Ed Harris.

Even while he was exploring on-screen opportunities, Dennard continued to be active on Seattle stages. He and the cast of Short Eyes jointly founded the Seattle Group Theatre in 1978, focusing on plays by playwrights of color, based primarily at the Ethnic Cultural Center Theatre in the University District and led by Ruben Sierra for 20 years. Dennard both directed and acted in plays like Fraternity and The Boys Next Door until SGT’s closing during the 1998 season.

In the past decade, Dennard has worked closely on multiple projects with Seattle writer/director Megan Griffiths. In her short film The Sound (2018), he plays an elderly father and Washington State Ferries worker who, in one poignant scene, lingers on the outside ferry deck, watching Seattle slowly shrink into the distance. The morning light reflects off of Dennard’s wistful gaze. He speaks only a few lines, but his face communicates so much — appreciation, contentedness and serenity.

“He’s very settled into who he is,” Griffiths says of working with Dennard. “You don’t feel a lot of pretense and he feels comfortable on camera. He’s very natural.” That on-screen ease comes through in his role in her 2018 film Sadie as well.

Since the pandemic began, Dennard has slowed his acting and directing pace, instead taking the time to focus on his health. But he and other BA/W alumni, including Rubee Taylor, David Roebucks and Kibibi Monie, are planning an exhibition to highlight the legacy of the Black-led theater and its founder Douglas Q. Barnett. Dennard sees preserving the history of BA/W as vital to future generations of Black actors.

“There are people who don’t even know that there was a theater up on 34th and Union,” says Dennard. “It’s important for us, the survivors, to get that out now so that younger folks can know what type of city this was.”

Black Arts Legacies Season 3 is made possible in part thanks to support from 4Culture.

Black Arts Legacies Writer

Seattle Rep’s most-produced living playwright tells complex Black stories with integrity and poetry.

The theater director and The Hansberry Project co-founder is fostering the next generation of actors, directors and playwrights.

Born from a 1960s urban relief program, the former synagogue has fostered generations of Black artists.

The Depression-era Black theater company celebrated Black storytelling with self-determined, interdisciplinary and collaborative works.

The driving forces behind Black Arts/West and CD Forum share a mission to tell Black stories in the theater.

This actor/director found her place in Seattle theater by embracing risk and seizing her own narrative.

The accomplished Seattle theater actor and playwright brings Black voices and histories to the stage.

With art, puppetry and real talk, this television pioneer prioritizes children of color.

The late director, producer, stuntman and teacher used film and video production to lift up the voices of Seattle’s Black community.

Thanks to our Sponsors

Your support helps Crosscut create projects like Black Arts Legacies. Learn how you can help with a one-time donation or recurring membership.

Support Crosscut