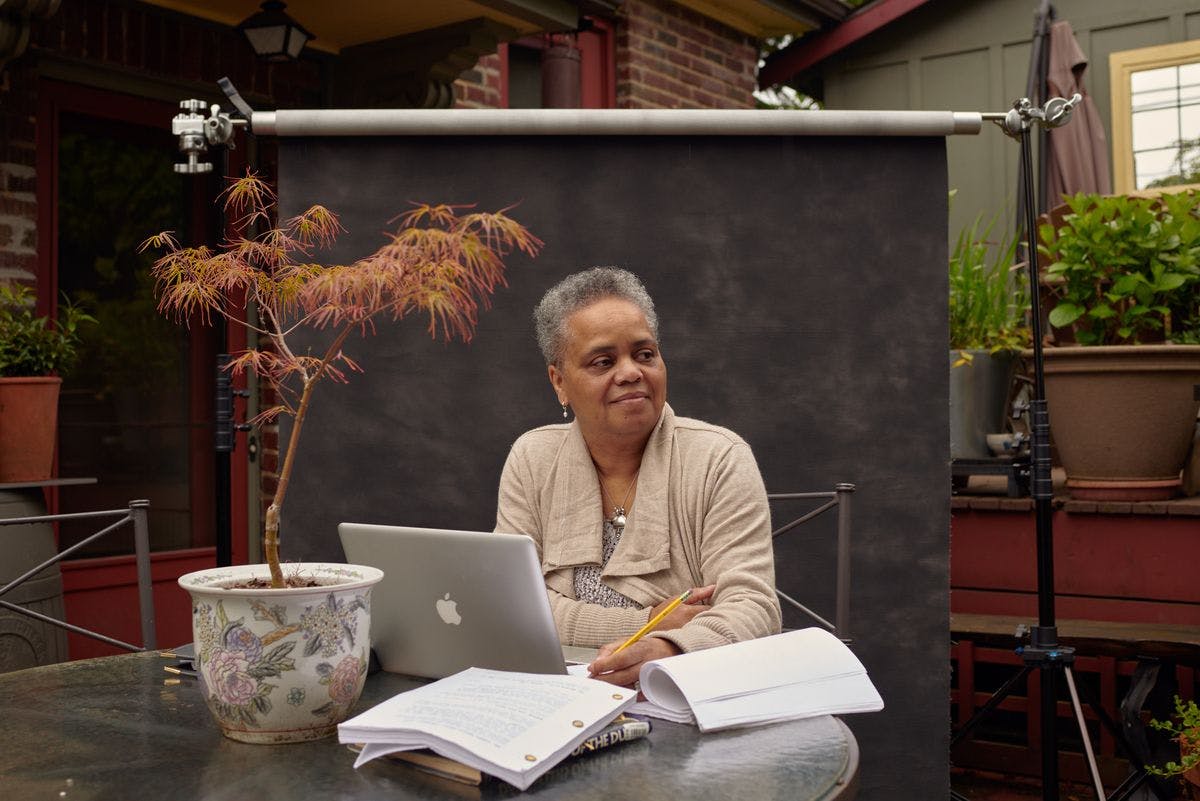

Valerie Curtis-Newton

The theater director and The Hansberry Project co-founder is fostering the next generation of actors, directors and playwrights.

Seattle Rep’s most-produced living playwright tells complex Black stories with integrity and poetry.

by Jasmine Mahmoud / May 16, 2023

“My mission has always been to tell African American stories of people who have been so silenced in this country,” says playwright Cheryl L. West. “To tell the stories that are about us: flawed, beautiful, exceptional people.”

Throughout her decades-long career and 20 full-length plays (and counting), the Seattle-based artist has embraced complex characters, celebrated the power of intergenerational stories and honored the rhythm, music and poetry of the African American vernacular.

Born in Chicago in 1965, West was a social worker and journalist before she became a playwright, and both jobs had a profound impact on her creative future. “Journalism teaches you how to write quickly, how to interview, and being economical with your language,” West says. “Social work teaches you that there are three or four sides to every single story. Individuals are extremely complicated.”

Complexity and empathy have been hallmarks of West’s work since her early days as a playwright, a career she grew into after finishing a graduate degree in journalism. “My need was to understand humanity from the inside out, not just report on it or or be in the role of spectator.”

That need to understand humanity is reflected in one of her first plays, Before It Hits Home. Written in the late 1980s, it centers on a bisexual Black man living with AIDS — and its impact on his family — at a time when such stories did not exist on stages or screens. For West, that was a risk worth taking.

“We as Black people do not always have a range of stories about ourselves,” she says. “Whenever I do any show that is showing some flaw or chaos, people are going to be suspicious: This is another way to degrade our people. I understand that, because we’ve earned the right to be suspicious, because we are people who have been maligned. But [I] also know my job as a writer is to tell the truth as I see it.”

When Before It Hits Home was staged at Washington, D.C.’s Arena Stage in 1991, somebody called in a bomb threat.

“It was the first such play about that subject,” recalls Tim Bond, artistic director at TheatreWorks Silicon Valley and formerly of Seattle Group Theatre, the venerable and now-shuttered company that first brought West to Seattle for the first-ever reading of Before It Hits Home.

“It was very well-written and passionate, and she had been doing social work so she had a lot of knowledge of the impact [HIV/AIDS] was having,” Bond remembers. “She won the [Group Theatre’s] Multicultural Playwrights Festival contest, we workshopped her play for a couple weeks and I just fell in love with her writing.”

Before It Hits Home went on to be produced off-Broadway, and earned West the 1991 Susan Smith Blackburn Prize for women playwrights.

Her plays have since been produced all over the U.S.: at D.C.’s Arena Stage; Chicago’s Goodman Theatre; the Actors Theatre of Louisville; the Oregon Shakespeare Festival in Ashland; the La Jolla Playhouse; on- and off-Broadway and elsewhere.

In 1999, West moved from Illinois to Seattle permanently. “Sharon Ott, who ran Seattle Rep at that point, said, ‘I’ll give you an artistic home. You come here, we’ll make you an artistic associate,’” West recalls.

For more than 20 years, that artistic home has allowed her to bring the stories and language she loves to life in Seattle. And she has stayed busy: West currently holds the title of Seattle Rep’s “most-produced living playwright” thanks to well-received plays including Holiday Heart (1994), Play On! (1998), Jar the Floor (2000), Birdie Blue (2007), Pullman Porter Blues (2012), Shout Sister Shout! (2019) and Fannie (2022).

Pullman Porter Blues focuses on three generations of railroad porters during one June night in 1937 — the night of the historic Joe Lewis/James Braddock heavyweight championship — on a train from Chicago to New Orleans. “Cheryl knew she wanted to tell a story that included multiple generations, because [the porter] position was often handed down,” says West’s longtime dramaturg Christine Sumption.

West’s love for generational stories owes much to her own familial influences, including two relatives she calls “masterful griots:” her Mississippi-born great-grandfather Willie Hawkins and her grandmother Lemmie Noy Hawkins. “I wanted to tell stories that reflected the truth and integrity of my great-grandparents,” West says.

The musicality of West’s dialogue flows from a similarly personal place. “When I would go South, they had certain phrases that [were] musical and poetic,” she says. “We may not use the King’s English, but we have such music and such interesting ways that we use language. I’ve always been interested in using our language and illuminating how poetic it is.”

In West’s comedy Jar the Floor, four generations of Black women bicker during the 90th birthday of the family matriarch, MaDear.

MAYDEE. (Exasperated.) MaDear, remember that little lecture I gave you on staying sane? So let’s keep that at the forefront. I tell you this every day, Papa’s been dead nearly a year and then we brought you up here …

MADEAR. Gal, you sho is talkin silly. (Throws bowl on the floor takes her cane and pounds the floor.) Jar de floor man. You ain’t dead. (She grins to herself). You feel dat floor move? Don’t you feel it? You hear him? Dat’s the sweet sound of my man….

My job as a writer is to tell the truth as I see it.”

No matter what story West is telling, she says she usually starts with character. Perhaps that’s why she’s drawn to stories of influential, complicated Black women such as Fannie Lou Hamer, the resilient Mississippi-born voting-rights activist she sketched in Fannie: The Music and Life of Fannie Lou Hamer and Sister Rosetta Tharpe, the Arkansas-born guitarist and “godmother of rock ’n’ roll” in Shout Sister Shout!.

“I love doing stories about unsung heroes because as women we’re always trying to figure out trailblazers [who] teach us how to be more courageous,” West says.

Both Fannie and Shout Sister Shout! feature live bands on stage, and music has long been an animating force and narrative tool in West’s work. “Music … can uplift a very weighted situation,” she says. “During the civil rights movement, when people would be getting beaten and water-hosed, people would sing. It’s that power, that you are not alone in the struggle.”

Audiences at Shout clapped along to Sister Rosetta Tharpe’s floor-shaking rock ’n’ roll while they followed her life as a queer Black woman guitarist across her enduring romantic relationship with singer Marie Knight, her three marriages, the church, the record industry and a leg amputation.

“Cheryl has an ability to see human beings from all sides, to embrace the possibility that whatever they’ve done, that they have good in them,” Sumption says. “She’s devoted to giving her characters another chance, not seeing them through a singular lens.”

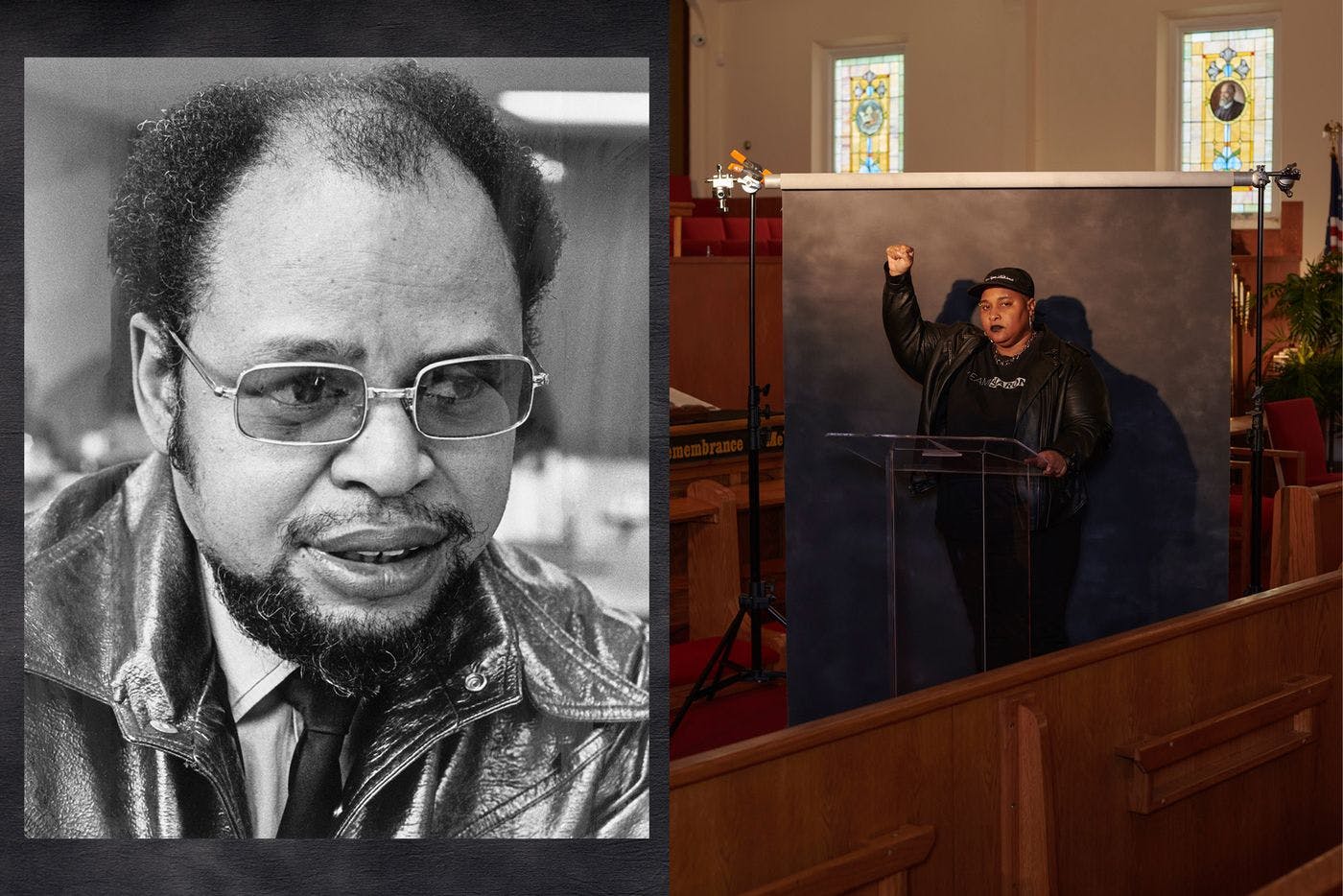

Beyond the stage, West is a private and introverted person with a powerful commitment to uplifting other Black artists. “She serves as a role model, beacon of hope and source of encouragement for other Black writers.” Sumption says. “She has consistently supported others’ work and helped make room at the table for artists such as Sharon Nyree Williams, Andrew [Lee] Creech, and many more.”

“Cheryl wants you on the project,” says Sharon Nyree Williams, a theater artist, playwright and CD Forum’s executive director, who remembers first meeting West as an intern at Seattle Rep in the 2000s. Months later, West requested Williams as her research assistant on an upcoming production.

West encouraged Williams to develop her theatrical work, including writing. “I was like, ‘No, no, no, no, I am not a writer,’” Williams recalls. “‘I am behind the scenes.’ And then — look at me now.”

Surveying West’s legacy and subject matter reveals clear similarities to those of August Wilson, the celebrated Pittsburgh-born playwright who spent the last 15 years of his life in Seattle.

“Seattle is lucky to have a playwright of her caliber,” Tim Bond says. “August was there for a number of years, one of the best playwrights in the history of the planet, and Cheryl is keeping it going there at Seattle.”

Currently, West is adapting The Wizard of Oz with composer Paris Ray Dozier. “Dorothy is a climate activist, and it’s all about home and being houseless,” West explains. “What does home really mean?” Retitled The Emerald City, the play is slated for Seattle Rep’s Public Works program, which presents work in collaboration with local artists and community groups.

“[Theater] is very healing in that maybe you come and see a story that is similar to [your own], or something that can make you see people differently, and wash you with some compassion,” West says. “That’s what theater can do. Hopefully the work that I create does that, to allow people to see their story, and the stories that I’m telling, and how might we be more accepting and loving of each other.”

Black Arts Legacies Project Editor

The theater director and The Hansberry Project co-founder is fostering the next generation of actors, directors and playwrights.

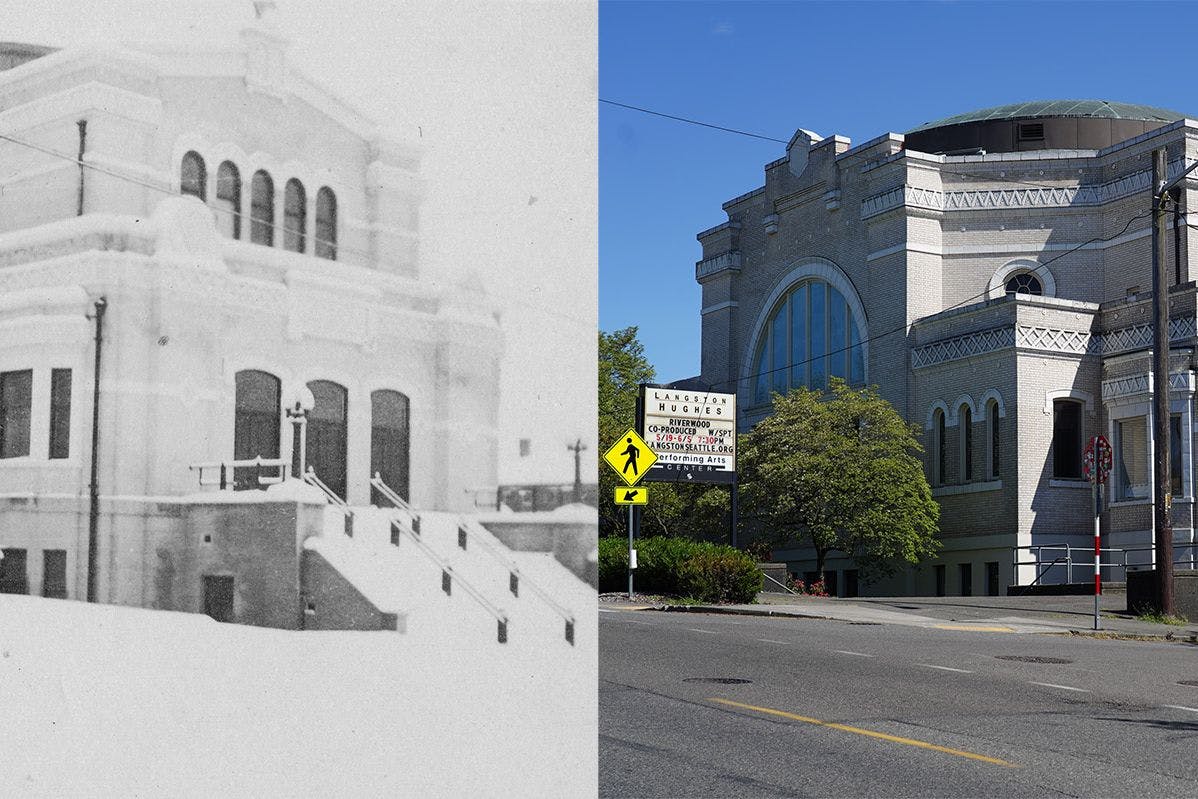

Born from a 1960s urban relief program, the former synagogue has fostered generations of Black artists.

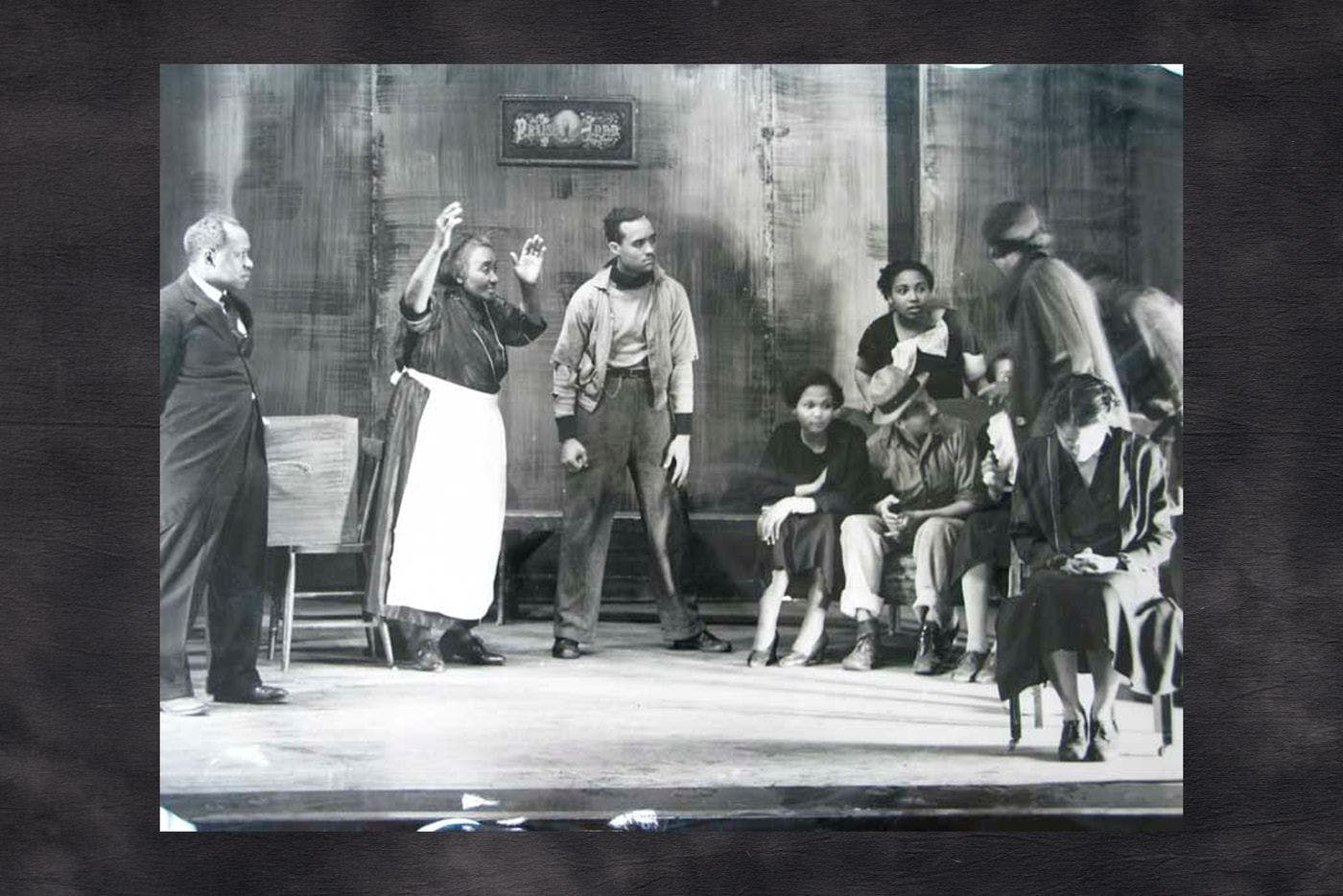

The Depression-era Black theater company celebrated Black storytelling with self-determined, interdisciplinary and collaborative works.

After landing on the stage unexpectedly, this Seattle actor/director’s 50-year career played a major role in the city’s Black theater scene.

The driving forces behind Black Arts/West and CD Forum share a mission to tell Black stories in the theater.

This actor/director found her place in Seattle theater by embracing risk and seizing her own narrative.

The accomplished Seattle theater actor and playwright brings Black voices and histories to the stage.

With art, puppetry and real talk, this television pioneer prioritizes children of color.

Thanks to our Sponsors

Your support helps Cascade PBS create projects like Black Arts Legacies. Learn how you can help with a one-time donation or recurring membership.

Support CrosscutLoading...