Cheryl L. West

Seattle Rep’s most-produced living playwright tells complex Black stories with integrity and poetry.

The Depression-era Black theater company celebrated Black storytelling with self-determined, interdisciplinary and collaborative works.

by Jasmine Mahmoud / June 27, 2023

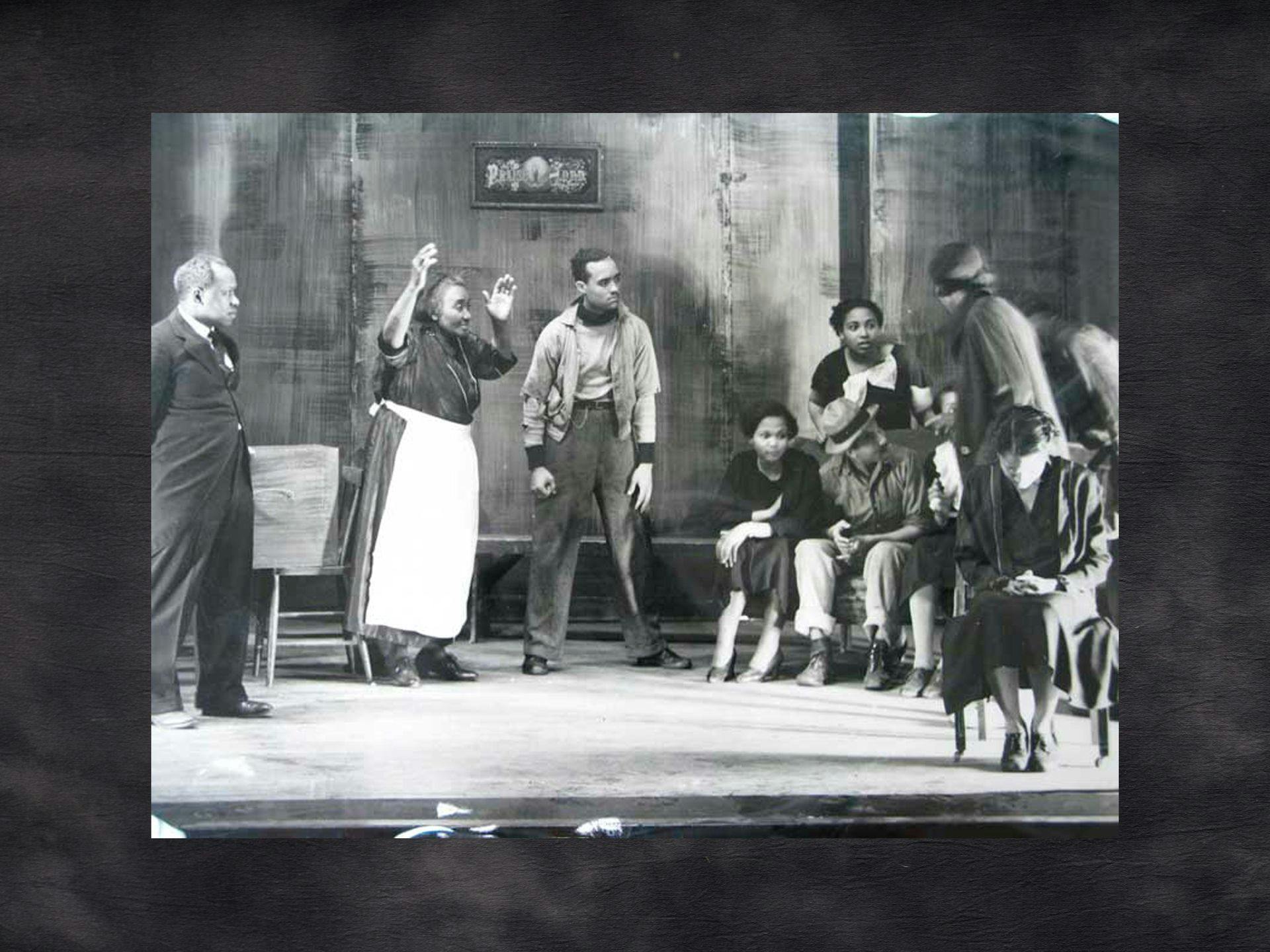

Something miraculous happened during a 1936 Seattle performance of the play Stevedore. Set on the Louisiana docks, the “race drama” by leftist playwrights Paul Peters and George Sklar follows Lonnie Thompson, a Black stevedore (or dockworker) who is among scores of Black men wrongfully accused after a white woman files a false police report.

At the play’s end, the Black characters build a barricade to protect themselves from white attackers. But at this Negro Repertory Company performance, as those mobs drew nearer, white audience members from Seattle’s Stevedore union rushed the stage to assist in the construction.

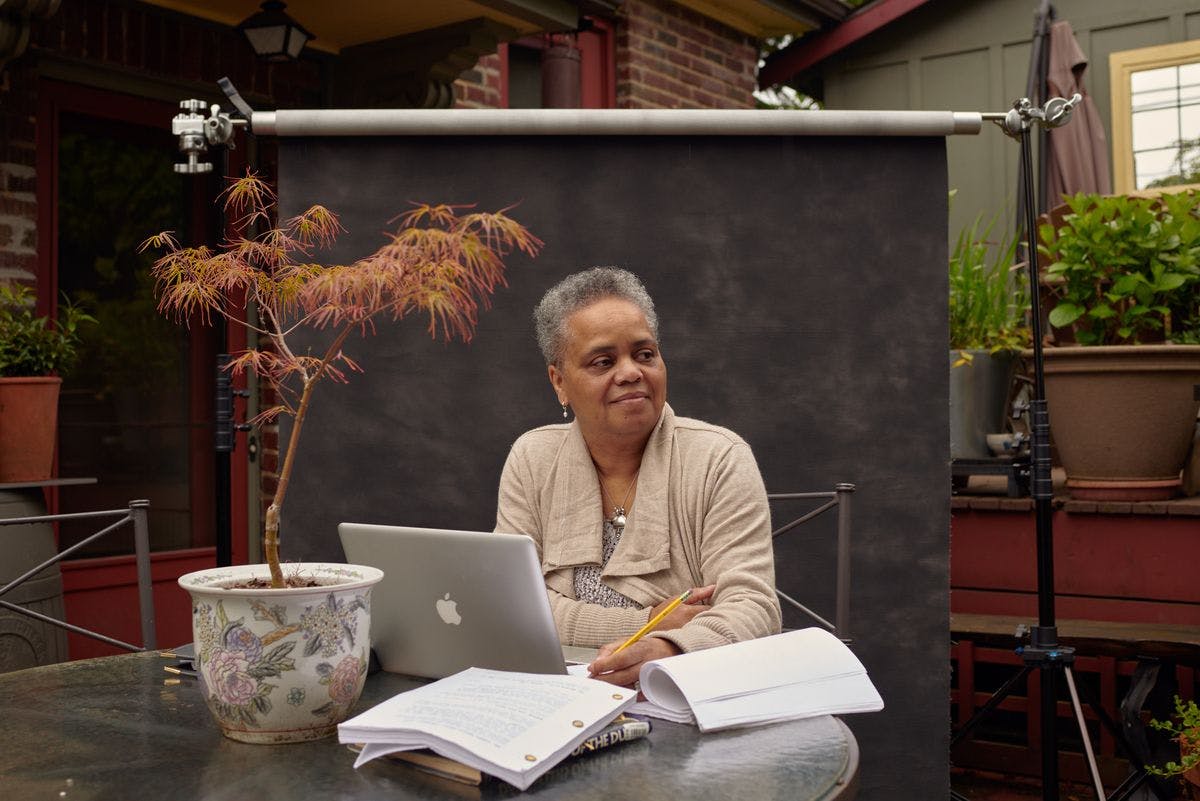

“They were so moved by the work that it encouraged them to do something,” says Seattle theater leader Valerie Curtis-Newton. “So they came on stage and built the barricade, and it was quite a sensation. I love the idea of theater that moves people to do something.”

Over its short lifespan — 1936 to 1939 — the Negro Repertory Company (NRC) moved countless audience members and accomplished a lot. The company presented 15 theatrical productions, including new works, addressing topics from antifascism and labor rights to Black history and an adaptation of Aristophanes’ Lysistrata.

Collaboratively led by Black Seattle artists, NRC developed works that, according to historian Kate Dossett, “put Seattle’s Black theater-makers on the map.”

In the process, NRC fostered the careers of dozens of Black artists who went on to influence the local and national arts community: playwright Theodore Browne, dancer Syvilla Fort, composer Howard Biggs, actor and later public school teacher Constance Pitter and actor Sara Oliver Jackson, who later performed with Black Arts/West.

Founded through the Federal Theatre Project (FTP), NRC was part of President Franklin Roosevelt’s Works Progress Administration (WPA) efforts to reduce poverty amid the Great Depression. It was one of 23 “Negro Units” across the country that specifically funded the employment of Black actors, playwrights, directors, musicians and technicians.

This living wage was especially important during the Depression, when the Black unemployment rate — at 50% — was double the national average. That astronomical figure likely drove another NRC hallmark: very large casts. Stevedore included 75 actors and singers, for example, and may well have been designed to employ as many people as possible.

“I was able to get on WPA with permanent status after about three months,” Seattle actor Sara Oliver Jackson recalled in a 1975 oral history with author Esther Mumford. “The pay was a big 80 dollars a month … a very good salary. You could rent a house and still have money left over to take care of other things.”

With that kind of support, the NRC was able to pioneer a collaborative and often interdisciplinary theatrical style that centered Black music, singing, dancing, storytelling and self-determination.

Noah, NRC’s first production, was a musical adaptation of a French play by André Obey. “We used Black music and introduced Black dancing to express the jubilation of Noah and his family when the flood recedes,” recalled Florence Bean James in her autobiography Fists Upon a Star. “The cast and chorus entered into the spirit … with zest and gave a very good show. Reviewers expressed amazement at the talent displayed by people ‘taken from the scrap-heap of unemployment.’”

It was Florence Bean James and her husband Burton James, two white theater artists who’d founded the Seattle Repertory Playhouse in 1930, whose application for Seattle’s Negro Unit was approved by the FTP (notably, chosen over those by Black applicants). The Jameses led NRC from 1936 to 1937; later, Black company member Joe Staton would lead NRC until its closing.

Although established by white theater-makers, NRC nevertheless amplified Black storytelling. This was thanks to Black leadership and collaboration, some of which had been established before NRC’s founding.

Many company members had previously performed in Black theaters and churches. In the early 1930s, the Jameses worked with Seattle’s First African Methodist Church, whose members (including Joseph Jackson and Oliver Jackson) acted in Black-music-filled versions of Uncle Tom’s Cabin in 1932 and In Abraham’s Bosom in 1933.

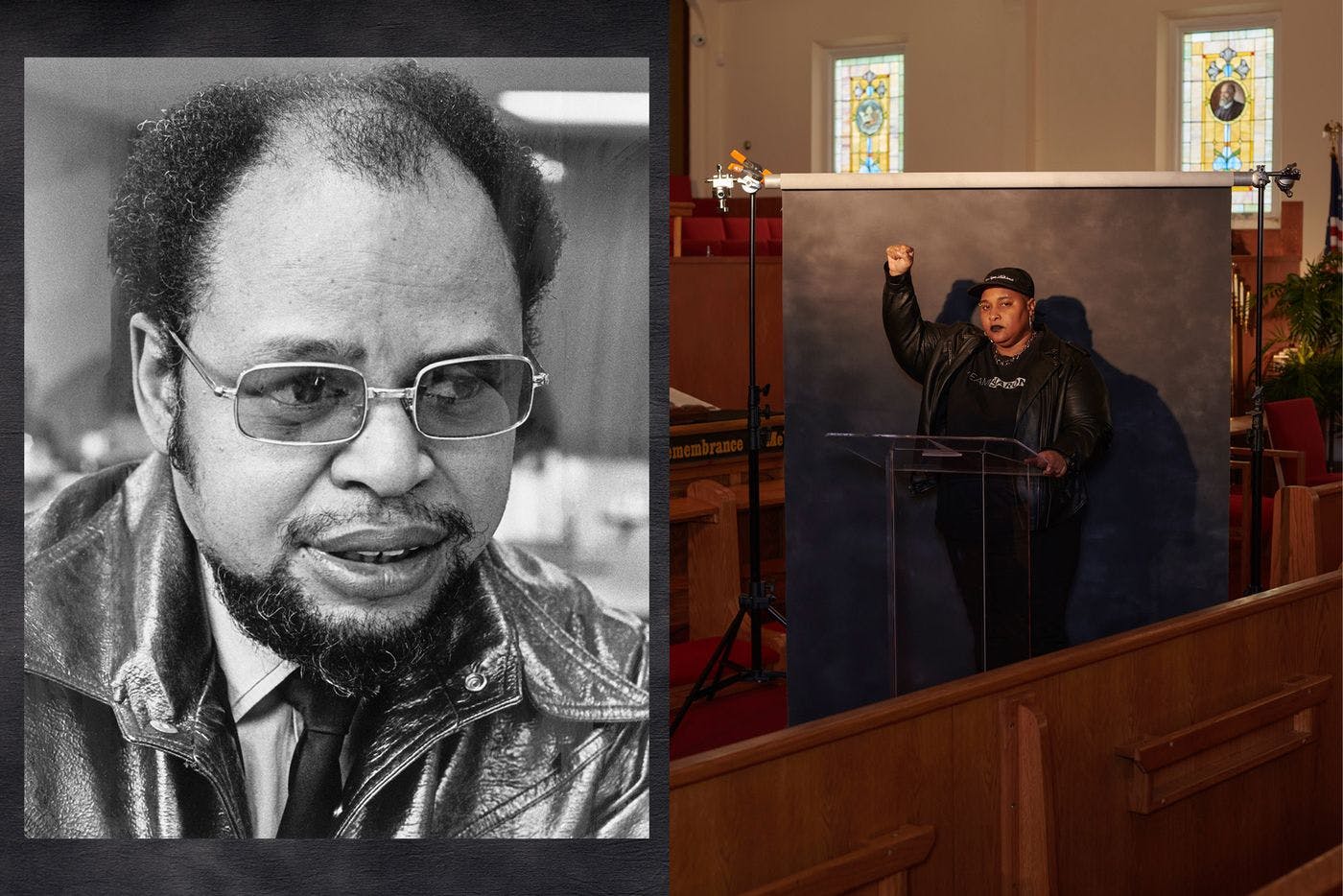

Another central NRC figure was Theodore Browne. In Stevedore, Browne played Lonnie Thompson, but his contributions went beyond acting. Born in Virginia and schooled in New York City, Browne moved to Seattle in the early 1930s, where he worked in theater.

In 1937, Browne adapted and directed Lysistrata, the ancient Greek “sex strike” play. The first performance, reviewed as having “charm and humor,” sold out 1,100 seats at the Moore Theatre downtown. Browne also wrote new works, including the Harriet Tubman-inspired A Black Woman Called Moses and Natural Man, an allegorical play about a Black railroad worker.

After he returned to New York in 1940, Browne brought Natural Man to Harlem’s American Negro Theatre, and later became a founding member of the Negro Playwrights Company in Harlem along with Langston Hughes and Theodore Ward. In this way Browne and other players spread NRC’s influence far and wide.

Other NRC productions included An Evening With Dunbar, a collaboratively created show drawn from the life and writing of influential turn-of-the-20th-century Black poet Paul Lawrence Dunbar, and Sinclair Lewis and John C. Moffitt’s antifascist play It Can’t Happen Here.

Simultaneously with 18 other FTP productions of the play across the U.S., It Can’t Happen Here opened October 27 — one week before the 1936 presidential election (when Roosevelt was running for reelection). Significantly, NRC was chosen to participate in this action over Seattle’s other FTP units, because, historian Mary Blackstone explained, it was “regarded as by far the strongest Federal Theatre unit in [Seattle].”

Just as powerful as NRC’s productions was the company’s choice not to perform certain other plays.

In 1936, NRC had initially slated Dorothy and DuBose Heyward’s play Porgy instead of Stevedore, but company members refused to perform it because of what they considered “the moral character of those characters,” Curtis-Newton says. “[Stevedore] still uses the n-word as much if not more than Porgy,” she clarifies, “but the characters in [Stevedore] are working men struggling against the system and coming together with like-minded white people to overcome racism.”

Throughout the company’s run, members refused to be stereotyped, including in marketing materials. “We ran into this business of the publicity man making caricatures to put on the front of the theater for Androcles and the Lion,” Jackson says in her oral history. “And we all protested very definitely, and they had to remove them, ’cause we weren’t going to even do the show.”

With its bold political stances and collaborative works, NRC set the tone for much of the Black Seattle theater that followed.

“[NRC] broke open a whole genre of theater and a community of theater by, for and of the African American community in Seattle,” says Tim Bond, formerly of The Seattle Group Theatre and currently artistic director of TheatreWorks Silicon Valley. “And [it] was one of the few theaters like that in the nation.”

Following Black Arts/West in the 1970s, The Seattle Group Theatre (or “The Group”) was founded, with a similar attitude of self-determination, in the late 1970s and continued through the late 1990s.

“The reason the Group formed was because a lot of BIPOC actors were not getting jobs at Seattle Rep, ACT [and] Intiman. And so they said, ‘Well, let's just do our own show,’” Bond says. “So that was the legacy that came out … all the way back from the Negro Repertory Theatre.”

The NRC ended in 1939 when Congress abruptly ceased funding for all FTP projects, alleging that the productions promoted communism. Such collaborative organizations are often lost to history, because they lack a single personality for future generations to hang a simple story on.

But the Negro Rep continues to inspire contemporary theater-makers today.

Case in point: Seattle actor/playwright Reginald André Jackson’s play History of Theatre: About, By, For, and Near, which premiered at ACT in January 2023. Curtis-Newton directed the play, which places 1930s Seattle theater in the larger context of Black theater-making.

“Reggie fell in love with that story and spent some time in the UW archives,” says Curtis-Newton, which is how History of Theatre audience members got to know Theodore Browne, Sara Oliver, Joe Jackson and Joe Staton, among other critical historical characters.

“Together with watching our ensemble light up on discovering new information about the people they were bringing to life,” Jackson wrote in an email, “one of my biggest joys has been sharing the existence of the NRC with our community.”

Author’s note: The NRC has been the subject of a great deal of research, some of it cited in this article. We also recommend that readers check out Sarah Guthu’s article “Negro Repertory Company,” hosted by UW’s Civil Rights and Labor History Consortium; and scholarship by Rena Fraden, Beth Osborne, and the late UW theater historian Barry Witham, who died in 2022.

Black Arts Legacies Project Editor

ARTIST OVERVIEW

Theater company

(1936-1939)

Seattle Rep’s most-produced living playwright tells complex Black stories with integrity and poetry.

The theater director and The Hansberry Project co-founder is fostering the next generation of actors, directors and playwrights.

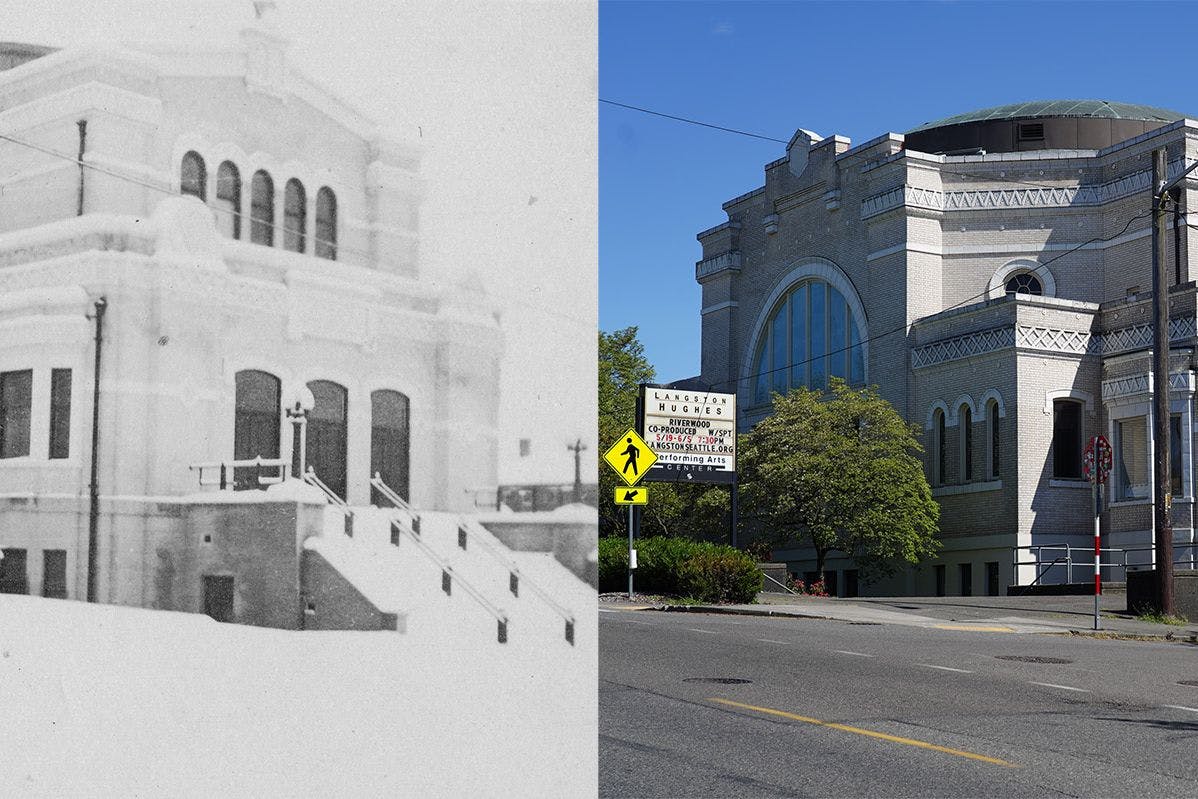

Born from a 1960s urban relief program, the former synagogue has fostered generations of Black artists.

After landing on the stage unexpectedly, this Seattle actor/director’s 50-year career played a major role in the city’s Black theater scene.

The driving forces behind Black Arts/West and CD Forum share a mission to tell Black stories in the theater.

This actor/director found her place in Seattle theater by embracing risk and seizing her own narrative.

The accomplished Seattle theater actor and playwright brings Black voices and histories to the stage.

With art, puppetry and real talk, this television pioneer prioritizes children of color.

Thanks to our Sponsors

Your support helps Cascade PBS create projects like Black Arts Legacies. Learn how you can help with a one-time donation or recurring membership.

Support CrosscutLoading...