Edna Daigre

A dance teacher beloved by generations of Seattle students, this longtime movement maven believes breath is life.

The Pacific Northwest Ballet’s first Black dancer went on to co-found a treasured performing arts school in Tacoma.

by Jasmine Mahmoud / June 1, 2022

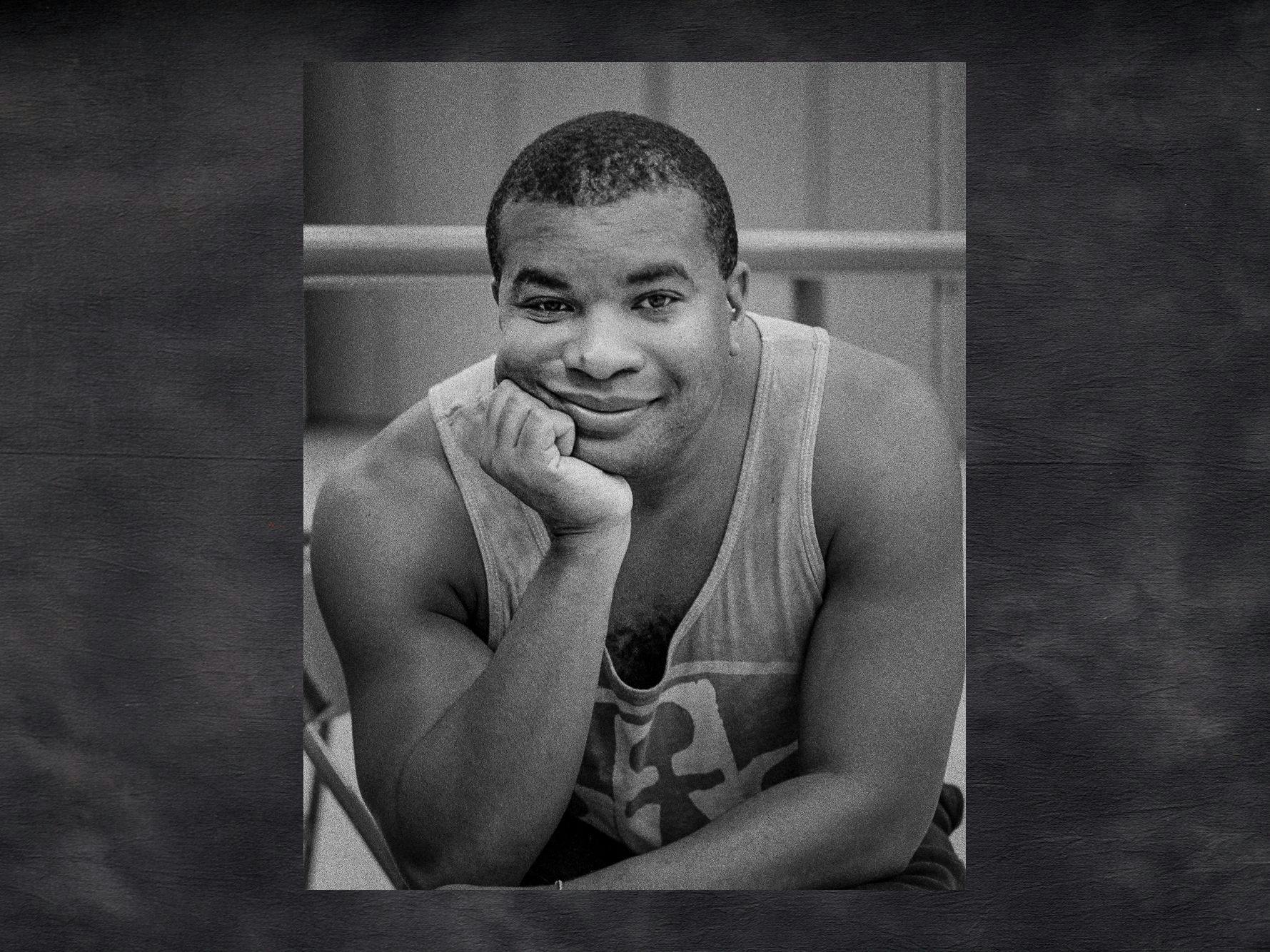

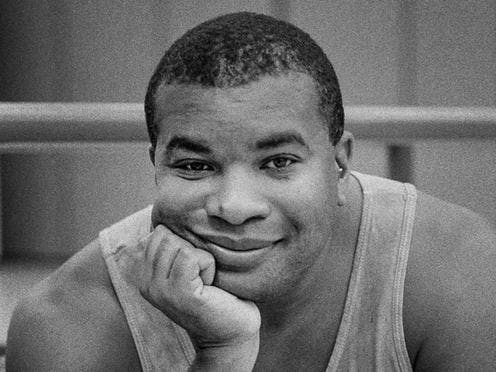

“Kabby knew everybody,” says Klair Ethridge. Executive director of the Tacoma Urban Performing Arts Center, Ethridge co-founded TUPAC with the late Kabby Mitchell. “It didn't matter where you went, somebody knows Kabby Mitchell III, because he was gregarious, bigger than life, a wonderful, good-hearted person.”

The first Black dancer in the Pacific Northwest Ballet, Mitchell joined the company in 1979 and stayed through 1984, reaching the role of soloist. “That's huge,” Ethridge notes. “People don't realize how big that is for an established dance company.” Mitchell went on to teach a variety of dance styles at various Pacific Northwest institutions (Evergreen State College, Cornish College of the Arts, University of Washington, Spectrum Dance Theater and Ewajo Dance Workshop) for more than 30 years, influencing generations of Northwest dancers.

Mitchell passed away in 2017 at the age of 60 from coronary artery disease, leaving a trailblazing dance legacy in his wake.

Though he faced tremendous odds in his career — as a Black ballet dancer, as a gay Black man, as a Black artist in the majority white Pacific Northwest — he won people over with his remarkable talent, shining personality and megawatt smile.

Confident and gregarious, Mitchell had a great sense of humor, says Gilda Sheppard, a sociologist, filmmaker, and fellow Evergreen faculty member. She recalls joyous memories with her dear friend: splendid Oscar-viewing parties, going out dancing together (“we could really jam,” she says) and the way “he always gently and compassionately put a spotlight on his friends.” That’s because Mitchell saw dance — and the arts in general— as a place for love, learning, exchange and growth.

Sheppard recalls that he was fond of quoting a James Baldwin line: “The role of the artist is exactly the same as the role of the lover. If I love you, I have to make you conscious of the things you don't see.”

In addition to being known for his incredible physicality, Mitchell could also flex intellectual muscle. “Kabby grew up with a literary consciousness,” Sheppard says. His mother was a prolific reader, and Mitchell became “a voracious reader” in turn. “He spoke at least four languages fluently: English, French, Italian and Spanish,” Sheppard says. “He could talk to anyone about any subject.”

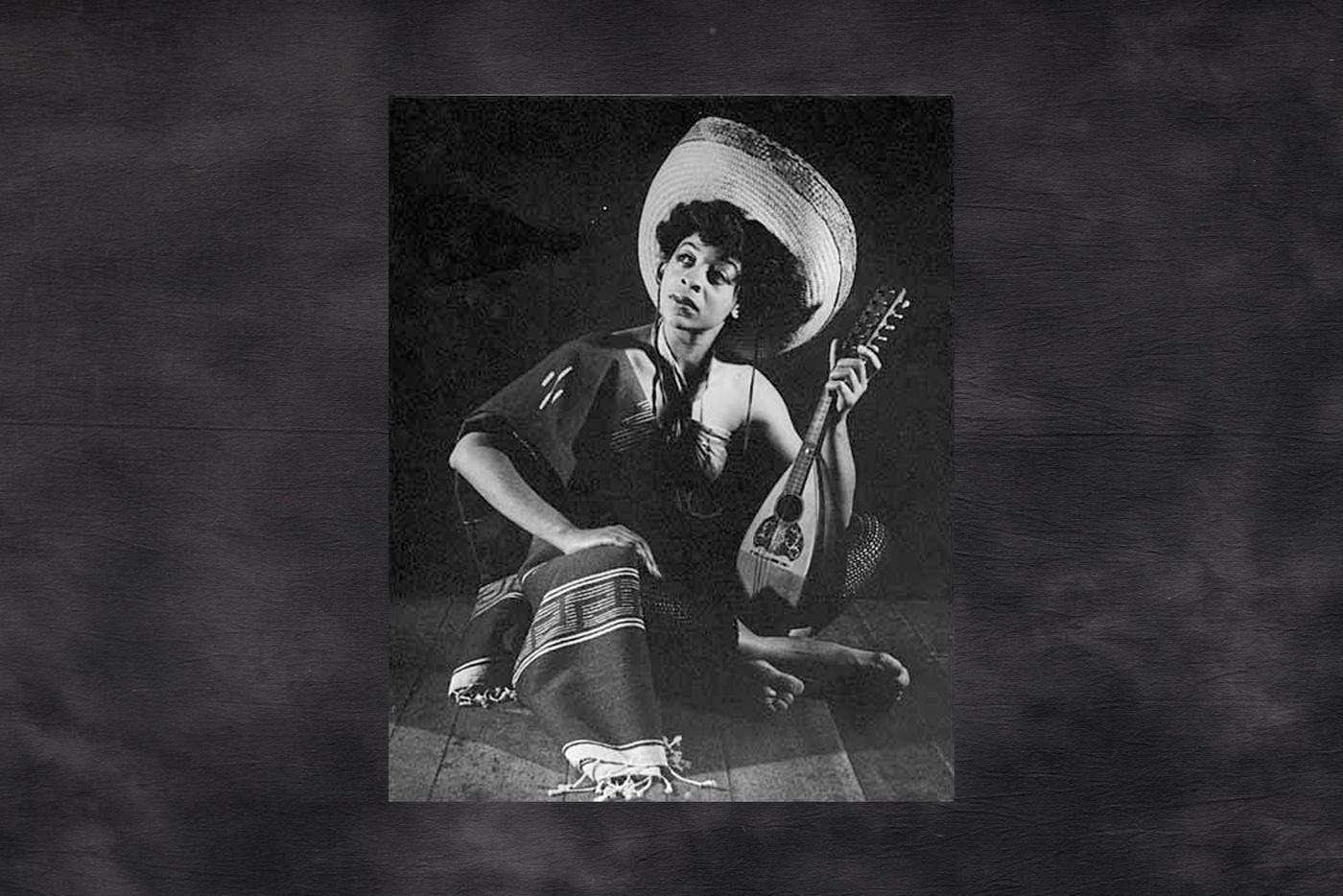

Mitchell, who grew up in the San Francisco Bay Area, might never have graced Seattle were it not for another Seattle dance legend: Edna Daigre, founder of the long-running Ewajo Dance Workshop. She happened to meet Mitchell in the late 1970s at a dance studio in Oakland, California. Impressed by his talent and his eagerness to teach so many techniques, including ballet, jazz and the Katherine Dunham Technique, she encouraged him to join her in Seattle. He made the move in 1979 and, after a brief residency at Ewajo, joined PNB. Daigre remembers him dancing around her living room when he first got to the city.

After receiving his MFA in dance from the University of Iowa in 1998, Mitchell became a professor at Evergreen State College in Olympia. “He was a perfect fit for Evergreen State College,” Sheppard says. “They were looking for someone who could [teach] ballet, modern, Afro Cuban, African and the Dunham Technique. I thought, ‘he's just an interdisciplinary, radically imaginative, elegant man.’”

While at Evergreen, Mitchell taught innovative classes that bridged dance with other forms of knowledge. “Interrogating the Classic” asked probing questions about art canons. Around the time that he died, he was teaching a class called “Dancing Molecules, Dancing Bodies,” which brought together scientific and artistic forms of inquiry.

“Kabby wasn’t [just] the first. No, no, no, no. Kabby kept that door open,” Sheppard says, regarding the importance of teaching and mentorship to Mitchell’s practice. In Mitchell’s obituary in The Seattle Times, Kiyon Ross (née Gaines) — another of the very few Black PNB dancers — gave thanks for Mitchell’s support. The former soloist, choreographer, teacher (and now director of company operations) at PNB said he remembered Mitchell going the extra mile to encourage him as a dancer. “He kept saying, you just have to keep working and keep positive,” Ross said.

Mitchell’s desire to be a mentor — and specifically to teach children — was because “he knew the power of dance,” Sheppard says. “He knew [dance] not just as an art form, but as a public health issue…,” Sheppard continues, “because we hold so much in our bodies, and he wanted to teach children so they [could] get it out or move it around or feel it inside.”

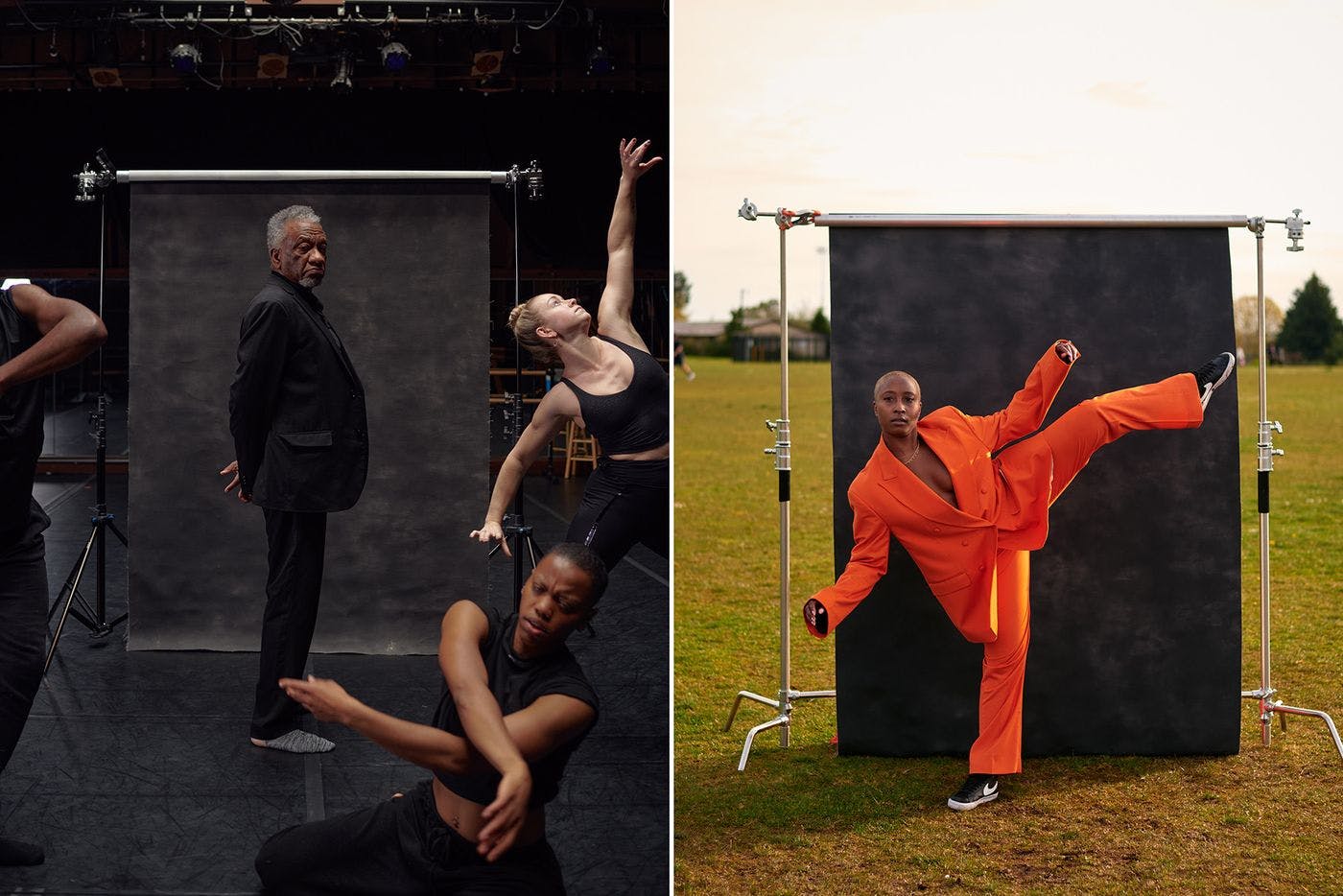

Eventually, Mitchell’s interest in using dance to examine self and community led to TUPAC, the performing arts school he co-founded with Ethridge. The two had discussed the idea for some time, including one day in the winter of 2017. They were listening to the radio when a Tupac Shakur song came on — at that moment, they decided that TUPAC should be the school’s moniker, and quickly brainstormed to fill in “Tacoma Urban Performing Arts Center” as the name.

That same month, February 2017, Ethridge filed for the school’s business license. Three months later, Mitchell passed away. In July 2017, two months after Mitchell’s death, TUPAC opened its doors.

Today, TUPAC offers a robust schedule of classes across styles, including hip-hop, ballet, flamenco, contemporary and West African, for students of all ages, plus master classes, summer intensives and a ballet school – reflecting a rigor and breadth that honors Mitchell’s skill. Guest teaching artists have included Jade Solomon Curtis, Donald Byrd and Amanda Morgan (the last of whom continues the line of Black dancers at PNB). “I think the school is truly his legacy,” Ethridge says. As of this writing, a theater in Mitchell’s name is being built at TUPAC.

“His heart was so into raising up Tacoma — particularly in the Black community — in arts education,” Ethridge remembers. “Because arts education helps expand young people's minds. It gives you an opportunity to experiment and see what is possible, and see short as well as long-term goals. I know Kabby would be ecstatic to know that there's a theater named for him based on an ideal and an idea that he had.”

A few months after Mitchell’s death, hundreds came together for a celebration of his life at Seattle’s Paramount Theatre. “They came from all over to attend Kabby’s memorial,” Ethridge remembers. “You had dancers from Alvin Ailey, Dance Theater of Harlem, Pacific Northwest Ballet, Spectrum Dance Theater, Nederlands Dans Theatre.” Packed with dance and heartfelt speeches, the celebration was a who’s who of the Black, dance and Pacific Northwest communities, showing Mitchell’s reach and impact.

Speakers included Melba Ayco, founder of Northwest Tap connection; Francia Russell, who along with Kent Stowell was artistic director of Pacific Northwest Ballet when Mitchell joined; Seattle Mayor Ed Murray and Edna Daigre.

Virginia Johnson, artistic director of the Dance Theatre of Harlem (Mitchell danced with the company in 1977) spoke movingly, saying she was honored to take part, but also heartbroken. “I’d give anything for the celebration to be for the living Kabby,” she said, paying tribute to Mitchell’s “long, beautiful legs, powerful presence and truth-speaking spirit.” Many of the speakers lovingly described themselves as “Kabby’s wife,” a term of endearment that Mitchell, as a gay Black man, would use with his close Black female friends.

Also at the 2017 memorial were many of his Evergreen colleagues, including Dr. Joye Hardiman, former executive director of the Tacoma campus, Dr. Maxine Mimms, founder of the Tacoma campus, college President George Bridges and Provost Ken Tabbutt, all of whom spoke glowingly about Mitchell and his positive effect on students.

Sheppard contributed a film for the event, with footage of Mitchell dancing — leaping, spinning and moving with poise. One of the best known images of Mitchell in motion shows him jumping impossibly high, doing the Russian splits in the air.

“I saw that famous image of Kabby with his hands extended and his legs extended. It's like, that is defying physics!” marvels Sheppard. “So I would say, ‘Kabby, how’d you get up there?’ And he said, ‘It’s not how you get up, my friend. It’s how you land.’ ”

Black Arts Legacies Project Editor

ARTIST OVERVIEW

Dancer, Teacher

(c. 1957-2017)

A dance teacher beloved by generations of Seattle students, this longtime movement maven believes breath is life.

Sixteen years after he first discovered tap, this Seattle dancer is finding his place in the lineage of an art form with deep roots in the Black community.

Pacific Northwest Ballet’s first Black woman soloist creates connections across disciplines.

The dancer, choreographer and instructor broke barriers and influenced generations of artists.

For these dancer-choreographers, social engagement takes center stage.

Thanks to our Sponsors

Your support helps Crosscut create projects like Black Arts Legacies. Learn how you can help with a one-time donation or recurring membership.

Support Crosscut