Watch: Cipher Goings

Sixteen years after he first discovered tap, this Seattle dancer is finding his place in the lineage of an art form with deep roots in the Black community.

A dance teacher beloved by generations of Seattle students, this longtime movement maven believes breath is life.

by Jasmine Mahmoud / June 1, 2022

When Edna Daigre moved to Seattle from Virginia in 1974, she was given a real Northwest welcome.

“It was 40 days and 40 nights of rain,” Daigre recalls. “It was just rain, rain, rain. I just couldn’t get over the fact that it was so dreary.” The move was prompted by her husband’s work in the military — he was a naval officer, which had taken them previously to Guam. This time, they landed with their two children in Mountlake Terrace. “The kids were going to school, everything was good, but there weren’t a lot of activities out there,” she says of Snohomish County. “So I started coming into the city.”

The city was Seattle, where Daigre met Douglas Q. Barnett, founder of Black Arts/West, and Lorna Prim Richards, who directed the performance company’s dance division. Soon, Daigre began teaching dance at Black Arts/West, too. And in 1975, she founded Ewajo Dance Workshop (the name comes from Yoruban slang for “common dance”), in an 800-square-foot space in Seattle’s Wallingford neighborhood.

She kept the studio open for more than 30 years, influencing untold numbers of young dancers who took her classes. “There would never have been an Ewajo if it wasn't for Black Arts/West,” she points out, “because that's how I came into the city.”

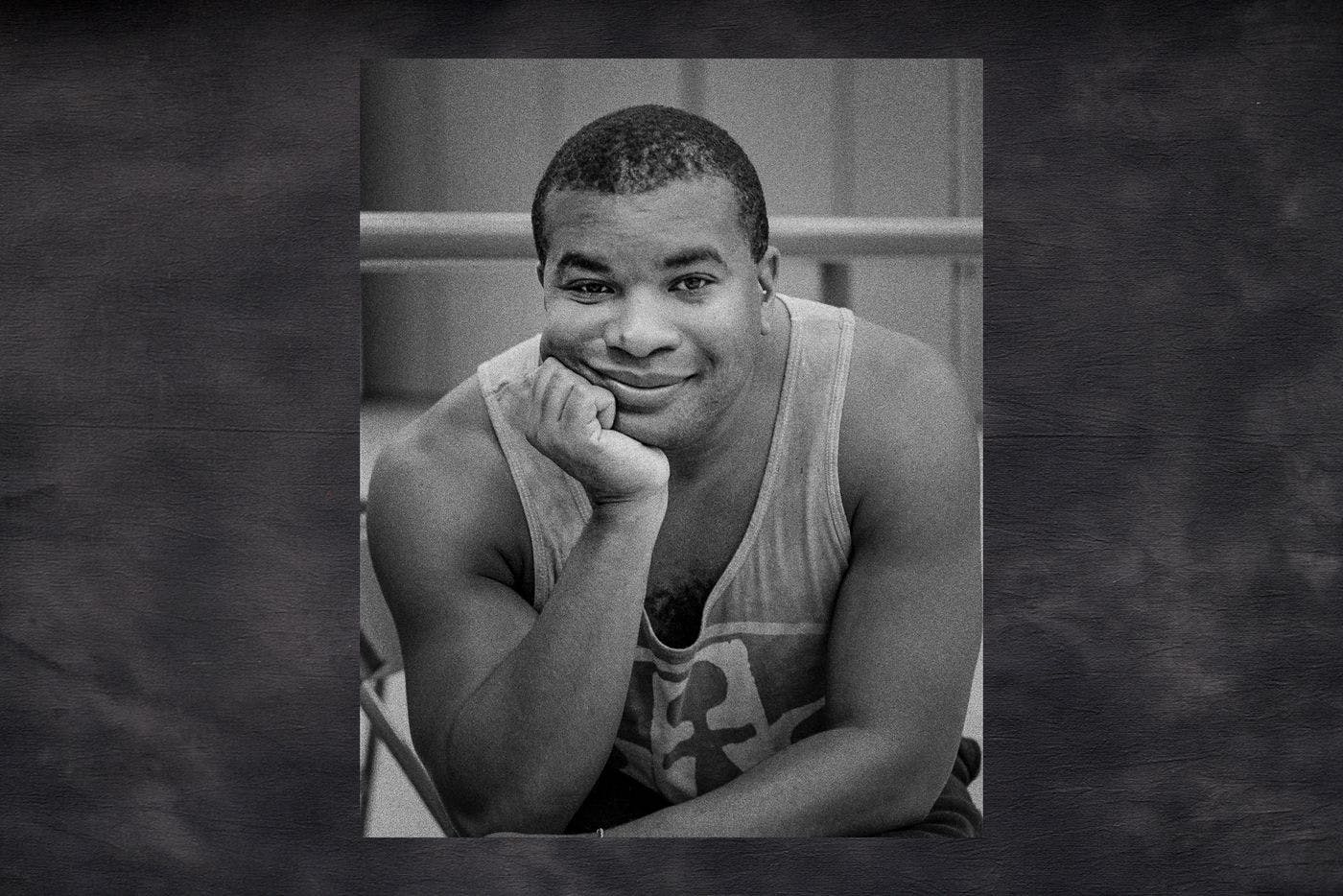

Dance has been a lifelong affair for Daigre, who turns 80 this year. Lithe and curious, with a well-rooted manner, she often wears drapey patterned fabrics that suit her commitment to free movement. She was drawn to the art form as a child growing up in Gary, Indiana, and, later, Chicago. “It was a way of expressing myself because my language skills were slow, ” she shares. “I wasn't a person with a lot of words. I was more physical. So my whole learning was physical and challenging, creatively challenging.”

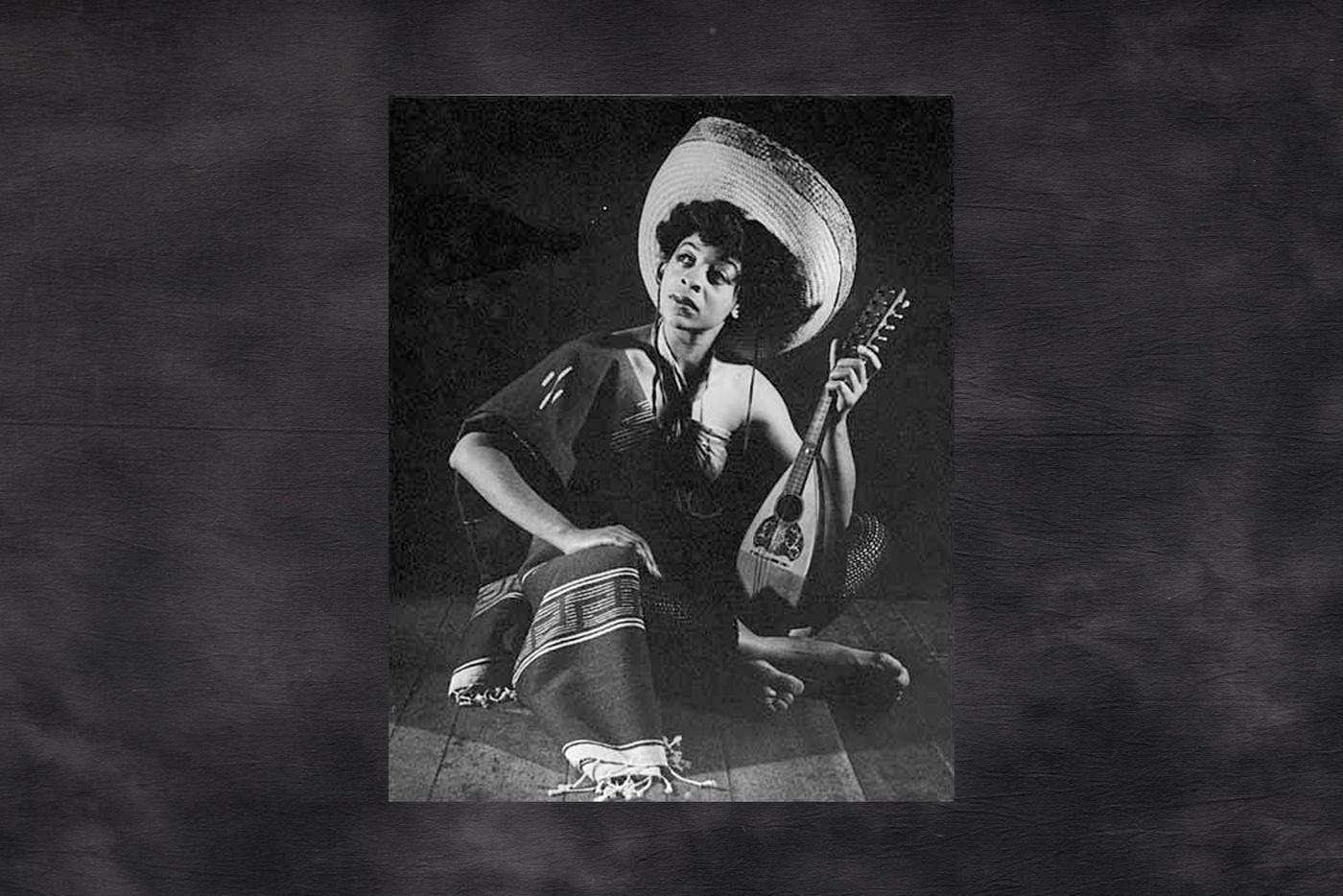

From early on she was influenced by Katherine Dunham, the foundational African American choreographer and anthropologist, who pioneered a dance technique rooted in Afro Caribbean forms. “She was the first dancer I saw who did something like what I wanted to do,” Daigre says. “And plus it was culturally based, Caribbean Afro dancing… . So it was really a lot of beautiful movements and beautiful costumes, beautiful stories.”

Daigre remembers it being “very exciting” to learn about through newspaper articles and a community outreach center in Gary. “When we would give a report in school, I would always select Katherine Dunham to tell a story about her,” she says. It’s perhaps no surprise that Daigre went on to become an expert in the Dunham Technique, a set of modern dance class exercises emphasizing rhythm and breath. “Breathing is life,” she says. “Through the breath, we move.”

To this day, breath, movement and physiology are integral to Daigre’s teaching methods. She believes these are the cornerstones of good health, combined with the fundamentals she learned during a stint in nursing school. The result is “dance as a healing power,” she says.

“The method of breathing is Pilates,” she explains. “The technique itself is Katherine Dunham's because it’s isolation and joint work. You get a chance to get familiar with the joints, and the range of motion that they can create through breathing and relaxing.” This is especially key for her most recent project: teaching seniors of color in a program called Dance for Health. Those classes, which include students 64 to 97 years old, are joyous celebrations of bodies in motion.

“What my class looks like is people coming together to understand what they want… in the moment,” she says. “We sit in a circle. Usually we start with a conversation, compassion, connections. I try to get people to understand themselves first — I go inside the body before I start focusing on the outside.”

For Daigre, dance has always been a communal affair — an activity for all ages, all people. She was committed to ensuring that Ewajo was a welcoming space, with “dance of everyone.” A 1996 Ewajo brochure details an after-school program with “dance classes that reflect Seattle's African-American, Brazilian, Filipino and Native-American populations.” Students were encouraged to take part in chat sessions to learn about and discuss social, cultural and historical issues. With performances around the city, the program had the goal of bringing people together and “make them feel included in the dance.”

One of the people Daigre brought into Seattle dance was Kabby Mitchell III, whom she met in the Bay Area. She encouraged him to move to Seattle, where he would be the first Black dancer to join the Pacific Northwest Ballet.

Daigre’s persistence has proved important in many ways — from maintaining Ewajo across several locations and decades to dealing with racism she frequently encountered.

When Ewajo moved to Capitol Hill in the 1980s, (at the intersection of 12th Avenue and Madison and Union streets), a fellow tenant — a woman who didn’t want to share the building’s bathroom with Daigre’s students — called the police on Daigre while she was teaching a class to young children. “What bothered me the most,” Daigre recalls, “is somebody like her could move in and make it very difficult.” When Ewajo moved to its final location, in Madison Valley (where it ran from 1989 to 2007), white residents nearby would often ask her for the manager, assuming she wasn’t the one running the space.

Yet Daigre still speaks of that Madison Valley location with pride. “We put a beautiful floor in. We had ceiling-to-floor mirrors and beautiful ballet bars inherited from Black Arts/West — oak ballet bars,” Daigre says. “It wasn't a big studio, but it was an open space of 800 square feet.” The space got a special assist from Gerald Tsutakawa, the famed Pacific Northwest sculptor, who, Daigre says, “was the one who really helped bring those ballet bars on the wall — because he knew about wood and sculpture.”

The Daigre dance story didn’t end with the closure of that space. Around the time Ewajo closed, her son, Chris, continued the tradition by opening his own dance studio, danceDaigre. And Edna Daigre has continued to teach, including at what was Martin Luther King School (now MLK Fame Community Center) in Madison Valley. “I have learned over 60 years or so,” she says. “I think I'm a better teacher now because I've had to live every bit of my technique and my foundation, and put it together so I can survive first, and then reach out for others to share and teach.”

Black Arts Legacies Project Editor

ARTIST OVERVIEW

Dancer, Teacher

(b. 1942)

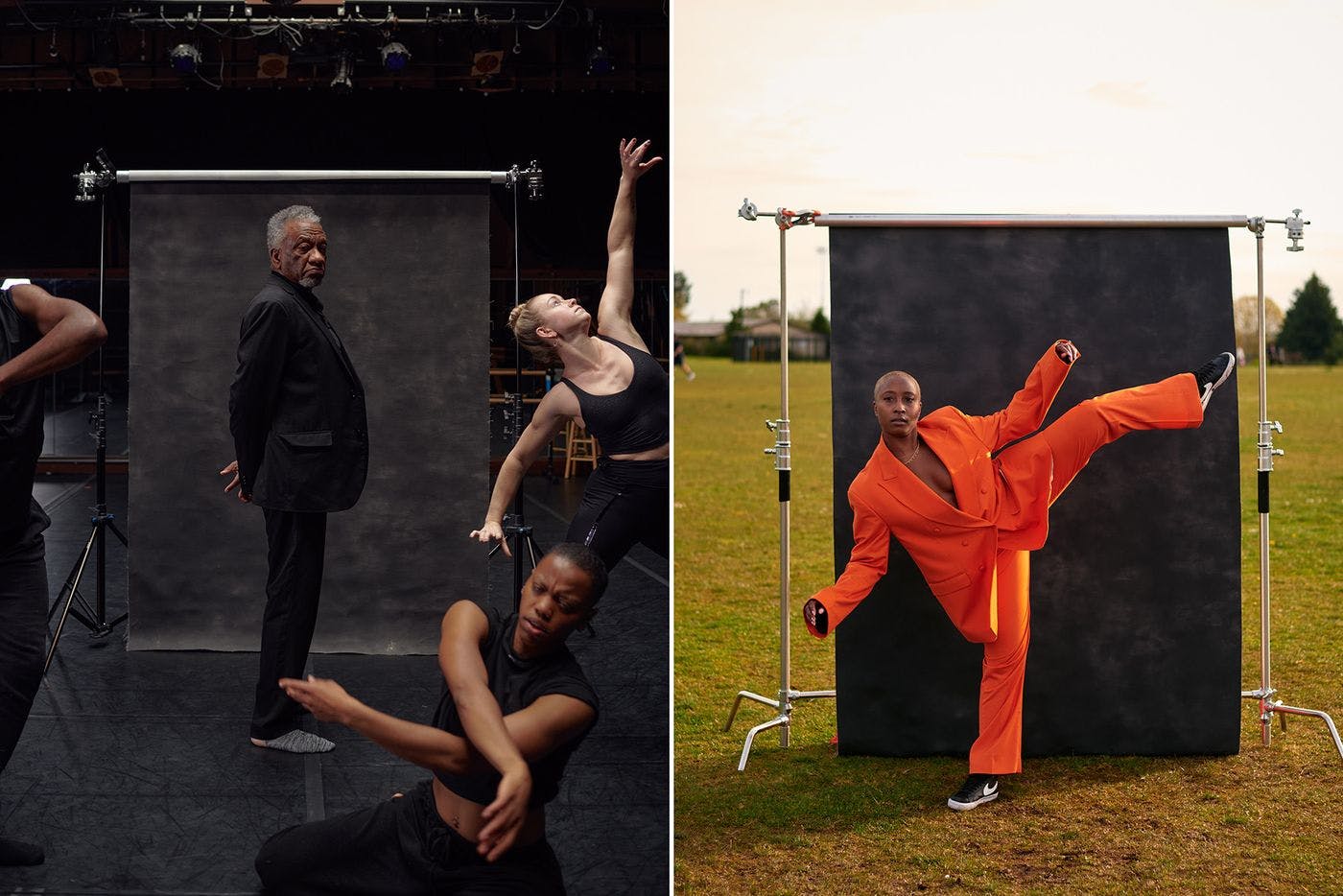

Sixteen years after he first discovered tap, this Seattle dancer is finding his place in the lineage of an art form with deep roots in the Black community.

Pacific Northwest Ballet’s first Black woman soloist creates connections across disciplines.

The Pacific Northwest Ballet’s first Black dancer went on to co-found a treasured performing arts school in Tacoma.

The dancer, choreographer and instructor broke barriers and influenced generations of artists.

For these dancer-choreographers, social engagement takes center stage.

Thanks to our Sponsors

Your support helps Crosscut create projects like Black Arts Legacies. Learn how you can help with a one-time donation or recurring membership.

Support Crosscut