Edna Daigre

A dance teacher beloved by generations of Seattle students, this longtime movement maven believes breath is life.

For these dancer-choreographers, social engagement takes center stage.

by Editorial Staff / June 1, 2022

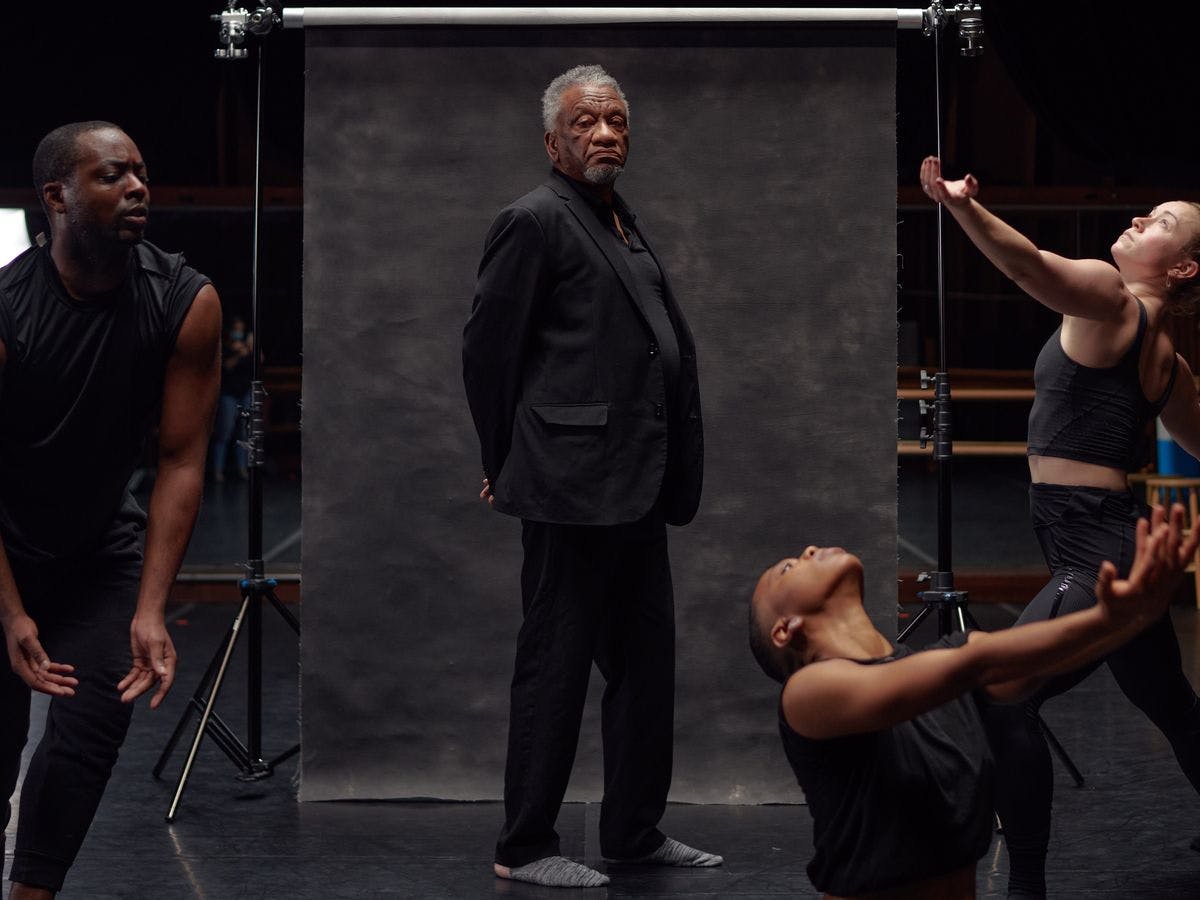

Donald Byrd and Jade Solomon Curtis do not shy away from hard conversations — they embrace them with their whole bodies. From gun violence to police brutality to slavery, the two Seattle dancer-choreographers have used movement to grapple with, embody and translate the persistent struggles of our era. For both artists, social engagement takes center stage, right alongside the twists and jumps of contemporary dance.

Byrd, 73, boasts a remarkable dance résumé: During his 40-plus-year career, he has danced for elite companies like Twyla Tharp and Gus Solomon Jr. He has been nominated for a Tony Award (for the Broadway musical version of The Color Purple), won the coveted Doris Duke Artist Award and had his work staged all over the world. No matter where his career has taken him, Byrd has been committed to his singular vision: pushing the boundaries of what contemporary dance should look, sound and feel like.

He launched Donald Byrd/The Group in 1978, and soon became known for combining punk rock with classical ballet and tackling social justice themes head on. His acclaimed 1996 piece Harlem Nutcracker was a reimagining of the classic Christmas tale from the perspective of a Black family. (He is currently reviving and revamping the piece, which emphasizes African American resilience, for a 2022 production.) Byrd has explored challenging historical moments such as the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre in the Alvin Ailey commission Greenwood and the history of blackface in 1991’s The Minstrel Show, which won the prestigious Bessie Award.

Seattle welcomed Byrd in 2002, when he took the reins as artistic director of the then-20-year-old Spectrum Dance Theater (he’s led it ever since). The company is an important component of his desire to foster “a rich and vibrant and large Black artistic community [in Seattle].”

Jade Solomon Curtis, 36, is a vital part of that community. After taking a dance workshop with Byrd when she was a junior in college at Southern Methodist University in Dallas, she eventually joined Spectrum as a dancer for four seasons. She has since carved out an inventive solo career of her own.

Curtis has directed award-winning dance projects that tackle language, grief and sadness in Black communities. Like Byrd, she has created performances designed to generate a sense of unease and soul-searching in the audience. For her 2017 performance Black Like Me, she created five solo dances about the N-word. (“It’s supposed to make you uncomfortable,” she told City Arts at the time. “It makes me hella uncomfortable.”)

Curtis also founded and leads Solo Magic, a nonprofit dedicated to supporting artists who are working to create socially engaged work. (Motto: “Activism is the muse.”) In addition, her Radical Black Femme Project is an arts residency program she designed “to build resources and solidarity in a community often pushed aside.”

This community-building instinct is also reflected in her approach to audiences: “I want to continue to make work that the average person who may not go into a theater, may have never experienced the theater, can be a part of the conversation,” she says.

Both Byrd and Curtis show us that dance can be more than simply beautiful — it is an opportunity to bring people into a communal space filled with movement, questions and deep dialogue.

A dance teacher beloved by generations of Seattle students, this longtime movement maven believes breath is life.

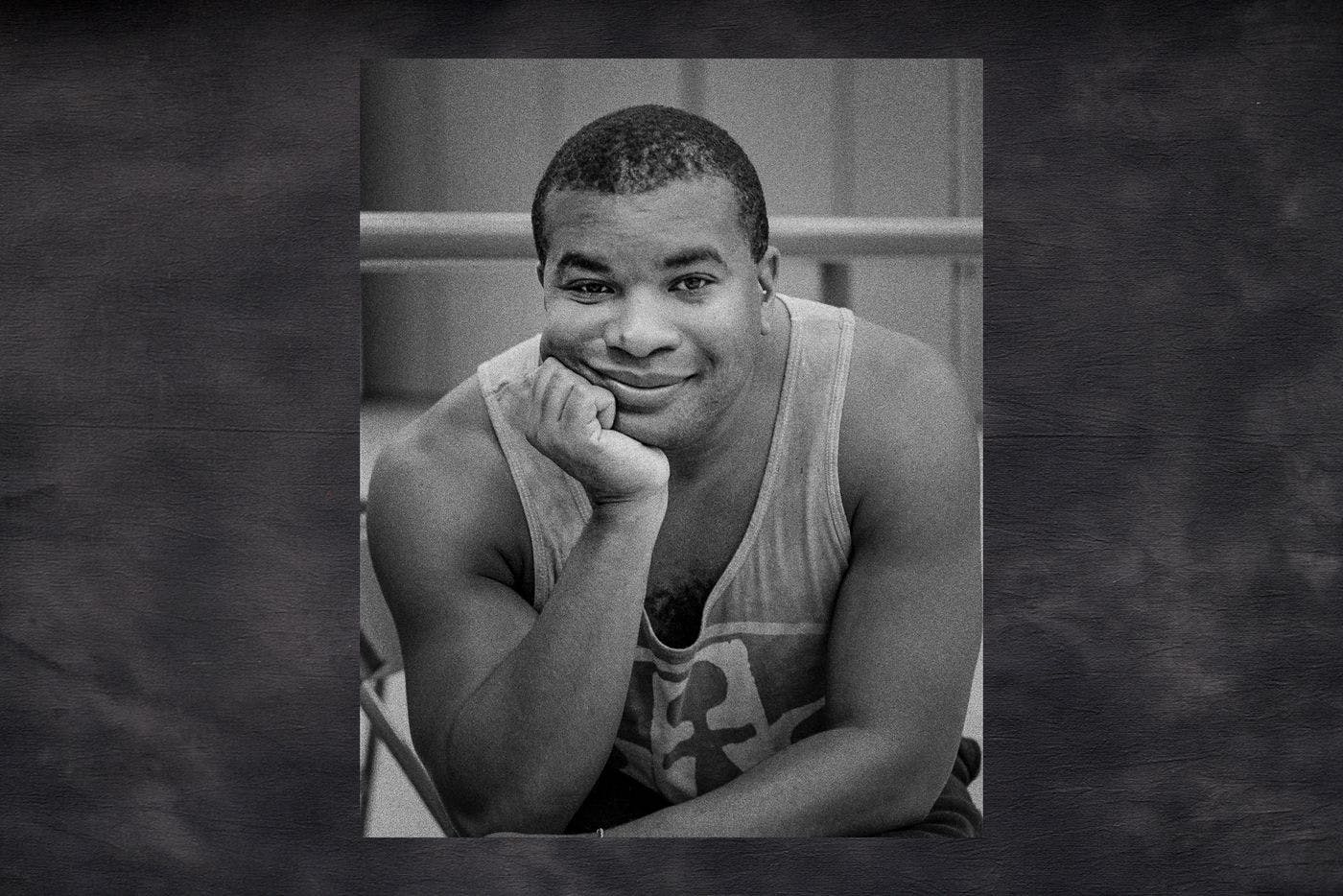

Sixteen years after he first discovered tap, this Seattle dancer is finding his place in the lineage of an art form with deep roots in the Black community.

Pacific Northwest Ballet’s first Black woman soloist creates connections across disciplines.

The Pacific Northwest Ballet’s first Black dancer went on to co-found a treasured performing arts school in Tacoma.

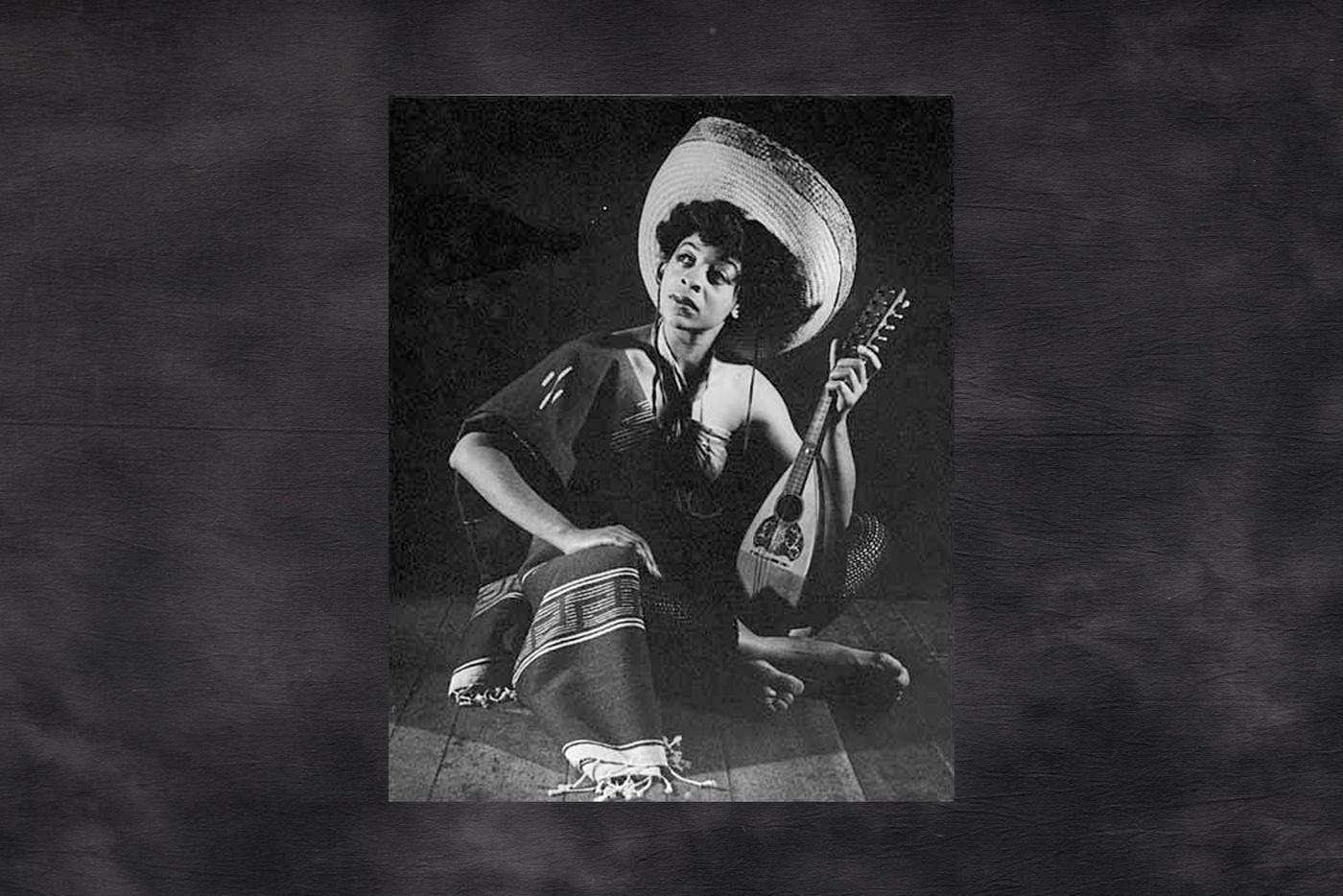

The dancer, choreographer and instructor broke barriers and influenced generations of artists.

Thanks to our Sponsors

Your support helps Crosscut create projects like Black Arts Legacies. Learn how you can help with a one-time donation or recurring membership.

Support Crosscut